p. 63

I. Racial-Facial Vision: Visual Truth, Trained Judgment, and AI

The truth of vision is shifting before our eyes—or rather, it is shifting invisibly through forms of nonhuman vision and image generation. Photographs and videos have long been subject to manipulation, an inevitable quality of nearly all technological media. Today, credible simulations thereof can be generated out of whole cloth woven by deep neural networks, or “generative AI.” Governments, corporations, and most individuals entrust machine vision—powered by other deep neural networks—to control borders, identify friends and foes, unlock phones, and perform numerous invisible operations with human or superhuman accuracy. Building on the videos and writings of Harun Farocki, Trevor Paglen outlined the necessary ideology critique nearly a decade ago:

Because image operations function on an invisible plane and are not dependent on a human seeing-subject (and are therefore not as obviously ideological as giant paintings of Napoleon) they are harder to recognize for what they are: immensely powerful levers of social regulation that serve specific race and class interests while presenting themselves as objective.1

Even as machine vision and its attendant practices of surveillance and control proliferate like wildfires, generative AI has made it more difficult to sustain claims to objectivity. Generative AI “photography” and “video” denote stylistic choices without any greater ontological claims to truth than drawings, animations, or erstwhile paintings of Napoleon.2 To be certain, AI imaging and machine vision have conceded little ground in their truth claims. Rather, they are the culmination of a century-long transformation of visual truth beyond declarations of mechanical objectivity.

In their landmark study on the construction of scientific vision and truth, Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison describe an early- to mid-twentieth century shift from “objective” images ostensibly untouched by human hands— p. 64 epitomized but hardly catalyzed by photography—to forms of scientific vision anchored in intuition, unconscious judgment, and pattern recognition that could be trained relatively easily; they dubbed this scientific ideal “trained judgement.”3 Their study, first published in 2007, could not address the revolution in machine vision and neural networks triggered by ImageNet in 2009; but it diagnosed the type of vision and truth claims made therewith.4 By the middle of the twentieth century, scientists were regularly trained to identify and differentiate complex images, such as abstract images of stellar spectra, the same way they identified and differentiated races in everyday life: unconsciously, intuitively, holistically, and at a glance. Daston and Galison described this mode of vision as physiognomic or “racial-facial.” Trained judgment—ostensibly stripped of its “racial-facial” baggage—remains a dominant paradigm for scientific vision to the present. (As much as AI marks multiple ruptures with the past, its trust in racial-facial vision marks a sordid and problematic continuity with earlier physiognomic endeavors. The potential biases implicit in the racial-facial mode of vision have been compounded many times over in AI training datasets, models, and applications.5) Trained judgment has ventured far beyond the confines of scientific vision through a range of machine learning technologies. Although no serious student of deep neural networks argues that they generate objective truth (hallucinations are features, not bugs, of most models), AI models are frighteningly accurate in many domains. Like mid-twentieth-century scientists, AI models are trained on images and data in such a manner that “accuracy should not be sacrificed to objectivity.”6

Trained judgment, intuition, physiognomy. Accuracy without objectivity. Images that appear like traces of reality but in fact are derived from other images. As Antonio Somaini explains:

[T]he new images generated by these algorithms are deeply related to the images contained in the datasets that were used to train them. For this reason, they may be considered to be images from images; that is, images produced through the algorithmic processing of vast quantities of other images.7

The rise of AI has infused new urgencies and adversities into the nexus of art, truth, and racial vision, specifically, the ways culture—undergirded by technology—processes racialized images of images in the age of AI. Among p. 65 the most profound responses to these new conditions, in all their complexity, is Arthur Jafa’s video BG (2024). The sections that follow tackle Jafa’s BG in relation to its source material (Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver), affective montage, appropriation and its legal discontents, and undercover racism, before returning fully to the question of visual truth and racial vision in the age of AI.

II. Taxi Driver, Redacted

BG, initially released with the title ***** (pronounced “redacted”), is named somewhat cryptically after the Hollywood actor Ben Gazzara, known for his gritty portrayals of problematic characters. The seed for BG was planted nearly fifty years ago, when filmmaker and artist Arthur Jafa (b. 1960) was still in high school and first saw Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976), the neo-noir thriller and gritty psychological study of a sociopath. The script, written by Paul Schrader, follows a taxi-driving Vietnam vet named Travis Bickle, played by a young Robert De Niro. Travis largely fails in love and life—today, we’d call him an incel—and he turns his vigilante rage toward a pimp—Sport, played by Harvey Keitel—who controls and abuses Iris, a child prostitute played by a twelve-year-old Jodie Foster. In the climactic scene—and the raw material for Jafa’s BG—Travis endeavors to free Iris by pumping lead into Sport, the brothel’s bouncer, and a mafioso client in a bloodbath equally calculating and grisly. Travis’s suicide attempt is stymied by a lack of bullets, and, with the arrival of the police, he forms his bloody fingers into the shape of a gun and mimes three shots to his head before passing out. An overhead tracking shot surveys the carnage in the room, down the stairs, through the hallway, and into the street, where a crowd has formed and police have secured the scene. Figure 2 Martin Scorsese, dir. Taxi Driver, 1976. Film still. Featuring Robert De Niro as Travis and Harvey Keitel as the pimp Sport. Figure 3

Martin Scorsese, dir. Taxi Driver, 1976. Film still. Featuring Robert De Niro as Travis and Harvey Keitel as the pimp Sport. Figure 3 Arthur Jafa. BG, 2024. Video still. Featuring Robert De Niro as Travis and Jerrel O’Neal as the pimp Scar. © Arthur Jafa. Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, and Sprüth Magers.

Arthur Jafa. BG, 2024. Video still. Featuring Robert De Niro as Travis and Jerrel O’Neal as the pimp Scar. © Arthur Jafa. Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, and Sprüth Magers.

This sequence—from the moment Travis pulls up in his taxi and confronts Sport through the massacre to the forensic tracking shot out the building—forms the core of Jafa’s BG. But whereas Scorsese’s pimp, bouncer, and client were all white, in Jafa’s BG—with the help of proprietary digital editing, no doubt aided by AI-assisted edge detection—they are all Black. Such was Jafa’s intuition upon first seeing Taxi Driver in the cinema: the pimp should have been Black. As he discovered only later, Schrader’s original screenplay indeed called for a Black pimp, bouncer, and john. (To speak with Daston and Galison, Jafa’s interpretation of Taxi Driver was driven by trained judgment not mechanical objectivity, intuition not impartial evidence.) p. 66 Amorphous racial fears catalyzed by the success of Blaxpoitation films convinced Schrader and Scorsese to switch the characters’ race to white, thereby suppressing the racial rage that courses through the movie.8 Jafa’s BG restores the racist animus animating Schrader’s script but redacted from Scorsese’s completed film.

Yet BG must not be understood as a restoration. As opposed to the recent rediscovery of Bélizaire, an enslaved Black subject initially depicted with the family of his enslaver but painted out in the early twentieth century (Bélizaire and the Frey Children, attributed to Jacques Amans, c. 1837), no footage was ever shot of a Black pimp, bouncer, or john. Unlike in Bélizaire and the Frey Children, the redactions in Taxi Driver, activated by nebulous racial fears, occurred before the work was shot, let alone completed. BG does not restore Taxi Driver to its unredacted original state so much as surface a form of intuitive vision reliant on—and defiant of—that very redaction. As Christina Sharpe has remarked in relation to Julie Dash’s 1992 film Daughters of the Dust, for which Jafa served as cinematographer, “Black redaction and Black annotation are ways of imagining otherwise.”9

At a basic level, then, Jafa’s BG reminds us that racism lurks even in the murder of an ostensibly white character, Keitel’s Sport. If this is all BG accomplished, it would have been a well-intentioned yet colossal waste of time, money, and artistry. For the race change and the opaque justification thereof are critical and Hollywood

commonplaces.10 Much more is contained and at stake in Jafa’s BG than a didactic lesson in U.S. racism, though U.S. racism still lies at the core of what BG makes palpable. Like Jafa’s prior videos—especially Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death (2016) and The White Album (2018), winner of the 2018 Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale—and in dialogue with them, BG is a landmark artwork that rattles the foundations of the ways we see and the ways we fail to see at the intersections of race, technology, visual culture, and art. But unlike Love Is the Message, which retains strong ties to the regime of mechanical objectivity and photographic evidentiary truth, BG operates in the more nebulous domain of intuition, racial-facial vision, and judgments trained in human and artificial intelligences.

III. BG: An Overview

Unlike his highly compelling music videos for Kanye West, Jay-Z, and others— which have collectively garnered tens of millions of streams—Jafa’s art videos p. 67 have extremely limited circulation, that is, they are viewable only in galleries and museums.11 The gap between experiencing BG and reading about it may be insuperable. But in any event, a sophisticated analysis requires multiple close viewings, beyond what normal spectatorship affords. I cannot remedy the inaccessibility of the video, but I can offer a precise summary that can serve as a reference for the remainder of this essay and future analyses.

BG comprises sixteen scenes, cinematically interlocked over 73 minutes. The opening scene is a one-for-one reproduction of the final shoot-up in Scorsese’s Taxi Driver with all the characters, save for De Niro’s Travis and Foster’s Iris, exchanged for Black actors in both body and voice. The bulk of the remaining scenes are variations—eleven in all—of the opening scene of BG: all the variations are shorter than the original; several contain alterations to the audio (including the near-absence of dialogue in several variations as well as subtle new dialogue in two); in the ninth variation, Travis unexpectedly blows out his brains. Around the halfway mark, Jafa includes a diner scene completely unaltered from the original film, save for a revelatory jump cut at its conclusion to make manifest its suppressed racism. From that moment, Jafa shifts much of the emphasis from De Niro’s Travis to the unredacted Black pimp (played by Jerrel O’Neal), whom Jafa has renamed “Scar” after the Native American villain (played in curious blue-eyed redface by German American actor Henry Brandon) in John Ford’s The Searchers (1956), a touchstone for Schrader. Three sequences—ranging from over five minutes to around 90 seconds—feature Scar in close-up, grooving to Stevie Wonder’s “As” (1976) or the Jackson 5’s “All I Do Is Think of You” (1975), or delivering a soliloquy. Despite a brief focus on Scar’s dead body as the last shot of the tenth variation, BG ends the way it began: consumed with Travis’s racist rampage. Figure 4 Arthur Jafa. BG, 2024. Video stills. The former white bouncer is now played by Montae Russel, a Black actor. © Arthur Jafa Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, and Sprüth Magers. Figure 5

Arthur Jafa. BG, 2024. Video stills. The former white bouncer is now played by Montae Russel, a Black actor. © Arthur Jafa Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, and Sprüth Magers. Figure 5 Arthur Jafa. BG, 2024. Video stills. The former white bouncer is now played by Montae Russel, a Black actor. © Arthur Jafa Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, and Sprüth Magers.

Arthur Jafa. BG, 2024. Video stills. The former white bouncer is now played by Montae Russel, a Black actor. © Arthur Jafa Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, and Sprüth Magers.

The video has a beginning and an end. But it can be, and often will be, viewed as a loop for which viewers enter and exit at random intervals— an experience simultaneously supported and destabilized by the frequent repetitions and variations of the opening scene. Reality and counterfactual hallucinations begin to blur—as they do in Scorsese’s film, which concludes with what can only be a megalomaniacal fever dream in which Travis awakens from a coma to find himself a celebrated vigilante hero. In BG, most of the sequences begin with Travis arriving from somewhere—in his taxi, on foot, etc.—calling into question the prior scene’s ending with a pathos and dark p. 68 humor that fall somewhere between Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence and Groundhog Day (1993). No matter where you start, to experience BG is to get lost in it, to grope in the dark, and to be subjected to Scorsese’s explicit physical violence and latent racial violence made manifest.12 BG is a highly cerebral work and those aspects avail themselves well to critical analysis. But its epochal significance is anchored in its affective impact and intuitive inculcation, facets of BG that I can only hope to intimate.

IV. Affective Units

John Akomfrah … said something that struck me, because I feel it’s at the core of almost everything that I do. He said that essentially what he tries to do is to take things and put them in some sort of affective proximity to one another. That really hit me because I think for me, in a nutshell, that’s what it really comes down to.13

Taxi Driver subsists in Jafa’s oeuvre not as a full-length feature film, but as a series of fragments: a high-contrast detail from the movie poster makes a brief appearance among 850 stills and two short moving images in APEX (2013); BG, despite its near-feature length, features only two scenes, one of which is the object of fetishistic obsession. Such obsessiveness is hardly a new phenomenon. Around the time Taxi Driver stormed cinemas, Laura Mulvey recognized that the ephemerality of cinema spawned all kinds of film industry fetishes: “a panoply of still images that could supplement the movie itself: production stills, posters and, above all, pin-ups.”14 With the advent of DVD technologies—mightily enhanced by the circulation of clips online—Mulvey theorized a “possessive spectator” who engages in a sadistic spectatorship that results in the fragmentation of narrative, fetishization of the human figure, and privileging of certain sequences.15 We are all now possessive spectators. De Niro’s “You talkin’ to me?” remains one of cinema’s most enduring fetishes (and is the centerpiece of Douglas Gordon’s 1999 video installation Through a Looking Glass). Given the number of YouTube clips that feature the final shootout, viewers of BG are surely not the first to watch the scene obsessively and in fragmentary form.

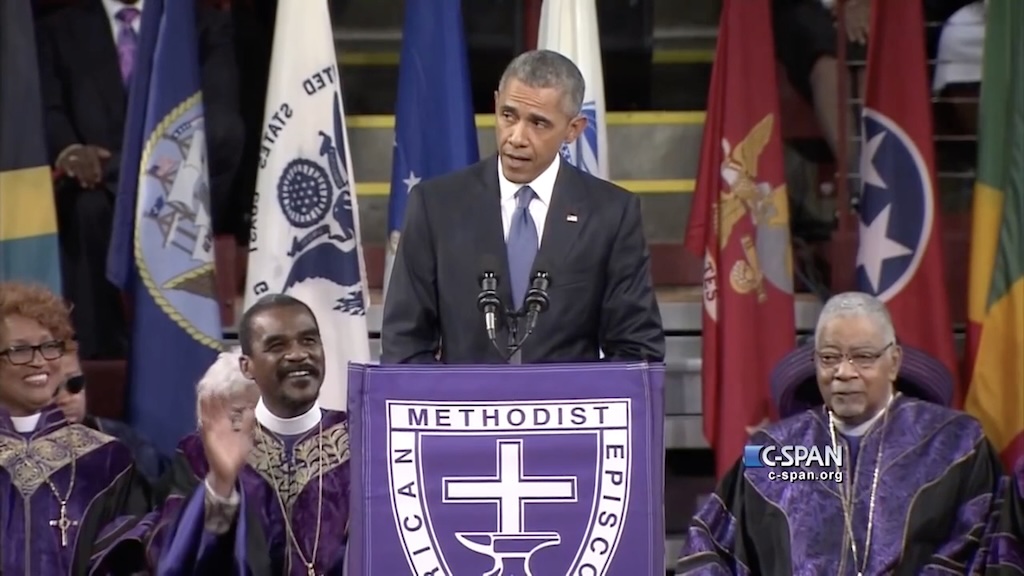

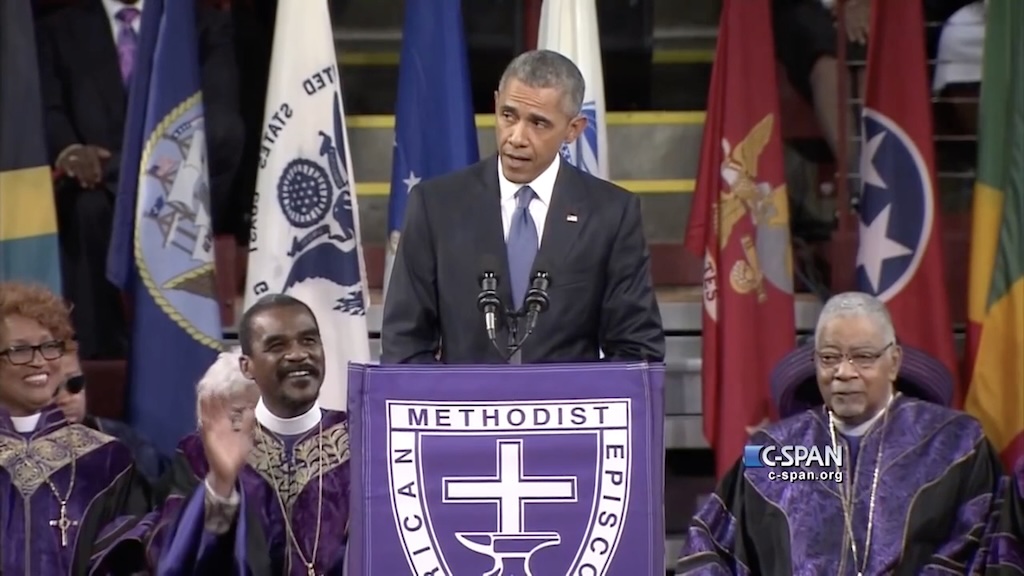

BG is hardly Jafa’s first negotiation with affective found footage.16 Nowhere is Jafa’s orchestration of affect more breathtaking than in his breakthrough video Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death (2016).17 (For a masterclass in possessive spectatorship, see Jafa’s shot-by-shot commentary on Love Is the Message, in a 2017 dialogue with Greg Tate.18) Compiled from original high-definition clips shot by Jafa and ample footage he found online, and set to Kanye West’s anthem “Ultralight Beam” (2016), Love Is the Message places p. 69 Black suffering and Black joy in affective proximity in order to construct a harrowing and layered portrait of African American life. Or as argued by Huey Copeland, the video constructs “forms of anti-portraiture that qualify the stilled repres entation of black figures in order to illuminate the dialectical relation between the self and the social.”19 Love Is the Message makes visible and palpable a quasi-ontological slippage between suffering and joy that lies at the core of Jafa’s conceptualization of Blackness.20 Figure 6 Arthur Jafa. Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death, 2016. Video stills. © Arthur Jafa. Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, and Sprüth Magers. Figure 7

Arthur Jafa. Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death, 2016. Video stills. © Arthur Jafa. Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, and Sprüth Magers. Figure 7 Arthur Jafa. Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death, 2016. Video stills. © Arthur Jafa. Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, and Sprüth Magers.

Arthur Jafa. Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death, 2016. Video stills. © Arthur Jafa. Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, and Sprüth Magers.

The mobilization of music—both Kanye West’s and the complex rhythms and intonations of the images and montage—is central to the video and to Jafa’s practice more broadly. Among Jafa’s central interventions is what he calls “declensions,” that is, the manipulation of frame rates to slow down and speed up the action on screen or, in Jafa’s 1993 description: “the sort of thing you see Scorsese utilize in Raging Bull for example but I think to different ends.”21 Jafa weaves declensions into a larger editing technique he calls “Black visual intonation”—that is, “the use of irregular, nontempered (nonmetronomic) camera rates and frame replication to prompt filmic movement to function in a manner that approximates Black vocal intonation.”22 When paired with an anthem like “Ultralight Beam,” Jafa’s Black visual intonation p. 70 pulses with affective intensity. However precise the selection and montage of the footage—some of it recognizable (by some), much of it unplaceable (for most)—Jafa’s basic units are not still photographs, single shots, or appropriated clips, although he regularly uses all three. They are units of affect. And the work of the piece—and of the viewer, as Tina Campt argues—“is the affective labor of juxtaposition.”23 Figure 8 Arthur Jafa. Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death, 2016. Video stills. © Arthur Jafa. Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, and Sprüth Magers. Figure 9

Arthur Jafa. Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death, 2016. Video stills. © Arthur Jafa. Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, and Sprüth Magers. Figure 9 Arthur Jafa. Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death, 2016. Video stills. © Arthur Jafa. Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, and Sprüth Magers.

Arthur Jafa. Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death, 2016. Video stills. © Arthur Jafa. Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, and Sprüth Magers.

Sound, image, still, moving, moving faster, moving slower. Jafa’s videos stimulate affective responses. As an arranger of affective units, Jafa partakes in a venerated and multifaceted strand of montage. Jafa’s “Black visual intonation” rhymes with earlier practices of montage, such as Sergei Eisenstein’s “tonal” and “overtonal” montage and the fusion of intellect and affect.24 Eisenstein famously included snippets of the slaughter of cows to deliver the affective intensity otherwise lacking from the fictional massacre of workers in his breakthrough film Strike (1925). Even more germane, Guy Debord, founder of the Situationist International and also an experimental filmmaker, created a number of appropriated found footage montage films, not least, one named after his illustrious and influential tract, The Society of Spectacle (1974). It is in these films that Debord best practiced détournement, which, p. 71 in Jacques Rancière’s astute reading, has nothing to do with Brechtian distanciation or demystification:

Détournement does not consist in making high culture prosaic or in revealing the naked reality behind beautiful appearances. It does not attempt to produce a consciousness through unveiling the mechanisms of the world to those who suffer from their ignorance of these mechanisms. It wants to take back from the enemy those properties that the enemy has transformed into weapons against the dispossessed. The essence of détournement is the Feuerbachian and Marxist transformation of the alienated predicate into subjective possession; it is the direct reappropriation of what has been put at a remove in representation.25

In Jafa’s hands, détournement reappropriates racialized affective units and, by bringing them into proximity with other affective units, redirects their energies—their genuine potencies—against the hegemonic cultural forces that seek to weaponize or neuter them.

Decades separate Debord’s found-footage montage films and those of Jafa’s. Nearly a century yawns between Jafa and Eisenstein. What was once an avant-garde practice—radical montage—became a mainstay of music videos, of which Jafa is a supreme practitioner both inside and outside the industry: Jafa’s Love Is the Message, scored to Kanye West’s “Ultralight Beam,” is no less a music video than his official music videos for West’s “Wash Us in the Blood” (2020) or Jay-Z’s “4:44” (2017). More broadly, mashups and video remixes have become internet commonplaces. It is hardly a stretch to say that the basic audiovisual unit of social media, whether an animated gif or an elaborate mashup, is a unit of affect. And so we must understand Jafa’s medium, techniques, and basic units as fully mainstream, as close to Kanye West and Jay-Z as to Debord and Akomfrah. This strikingly successful double life demands recognition. Love Is the Message, despite its highly limited circulation, is widely considered among the most important artworks of the twenty-first century. And while the closely related “4:44” has been viewed over 25 million times on YouTube alone, it has garnered vastly less critical attention. Whether withdrawn into elite art spaces or circulating freely online, Jafa’s mastery of affect has made him among the most consequential and popular artists of our time.

V. Appropriation Art Is Dead, Long Live Appropriation

The appropriation of affective units is, at best, in legal limbo. Jafa’s montage work is reminiscent of the early days of hip-hop, before it was targeted by intellectual property law such that every sample required rights clearance, p. 72 which effectively outlawed the sound walls of Public Enemy and other early groups.26 (With AI, we are once again in a Wild West of copyright law with unforeseeable outcomes.27) Hip-hop survived and thrived, of course, but in a fundamentally altered form. Jafa’s videos are audiovisual echoes of early hip-hop, with a range and density of sampled appropriations largely unmatched since. A few examples: Jafa’s 2013 montage work APEX comprises some 850 images, for which he cleared no rights (as far as I am aware). His breakthrough piece, Love Is the Message, contains numerous clips from a range of online and commercial sources, none of which, to my knowledge, were licensed—although several are emblazoned with C-SPAN, New York Times, or Getty Images® watermarks. And, most relevantly, there is no indication in anything I have read that Jafa cleared rights to remake the end of Taxi Driver. This is a striking move in 2024, given that barely one year earlier the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the Andy Warhol Foundation in a copyright infringement lawsuit, a dubious decision that was supposed to have a chilling effect on all artists engaged in appropriation.28 Even more recently, Richard Prince, the most notorious Appropriation artist still working in the idiom, was forced to settle with photographers Donald Graham and Eric McNatt after nine years of litigation over the copyright infringement of their photographs of a Rastafarian and Kim Gordon, respectively. The settlement included the requirement that Prince relinquish the physical and intellectual property related to the works—that is, the works are no longer considered Richard Prince paintings—and the photographers can now do anything they want with them, including destroying them, repurposing them, donating them, so long as they don’t sell them.

Jafa, in turn, has thrust himself into the center of this debate. How? Implicitly and prominently by appropriating Taxi Driver without permission. But also explicitly and subtly in a concurrent exhibition at 52 Walker, BLACK POWER TOOL AND DIE TRYNIG (2024), where, upon entering a p. 72 winding, black enclosure (Picture Unit [Structures] II, 2024), viewers confront a series of gruesome and overdetermined images, not least Richard Prince’s 1993 appropriated image Untitled (Girlfriend), featuring a young blonde in a skull-and-bones cropped tube top beside a motorcycle.29 The appropriation of Richard Prince’s appropriation—in an exhibition chock-full of appropriations—must read as a throwing down of the gauntlet: 1980s Appropriation Art is dead; long live Jafa’s appropriations. But Jafa’s meta-appropriation may have been too clever by half. Jafa largely filled BLACK POWER TOOL AND DIE TRYNIG with appropriated images transformed into paintings, sculptures, and other collector knickknacks, such as Jim Marshall’s 1971 portrait of Miles Davis, here mounted on shaped aluminum, with an explicit nod to Cady Noland, who is also featured in the fancy fandom collection titled Large Array II (2024). Like Prince’s recent works, these objets d’art carry multivalent sophistications that deserve to be studied in depth; however, they betray scant evidence of the commentary or critique—as courts are now poised to understand the terms—often required for fair use claims and in ample evidence in works like Love Is the Message and BG. Figure 10 BLACK POWER TOOL AND DIE TRYNIG, 2024. Installation view, 52 Walker, New York (April 5–June 1, 2024). © Arthur Jafa. Courtesy of the artist and 52 Walker, New York. Photography by Kerry McFate. Figure 11

BLACK POWER TOOL AND DIE TRYNIG, 2024. Installation view, 52 Walker, New York (April 5–June 1, 2024). © Arthur Jafa. Courtesy of the artist and 52 Walker, New York. Photography by Kerry McFate. Figure 11 BLACK POWER TOOL AND DIE TRYNIG, 2024. Installation view, 52 Walker, New York (April 5–June 1, 2024). © Arthur Jafa. Courtesy of the artist and 52 Walker, New York. Photography by Kerry McFate.

BLACK POWER TOOL AND DIE TRYNIG, 2024. Installation view, 52 Walker, New York (April 5–June 1, 2024). © Arthur Jafa. Courtesy of the artist and 52 Walker, New York. Photography by Kerry McFate.

Jafa’s legal standing vis-à-vis copyright, fair use, and appropriation may be beside the point. As law scholar Xiyin Tang has argued in a recent theoretical and empirical study of artists’ appropriation practices, community norms—rather than legal strictures—play an outsize role in the vast majority of cases.30 Despite the Supreme Court’s recent ruling in Warhol and other prominent copyright cases, advanced art largely operates outside of copyright law.31 (It certainly helps that Jafa and his gallerists rigorously suppress the online circulation of his works, limiting their effect on the potential market of the music copyright holders; copyright-holding photographers whose work has been appropriated by Jafa may be less sanguine.) Left to its own devices, art tends to operate in intellectual property’s “negative space,” p. 73 that is, “substantial area[s] of creativity into which copyright and patent do not penetrate and for which trademark provides only very limited propertization.”32 In place of external legal strictures like copyright, internal community norms govern behavior. A key model for such internal regulation is hip-hop and its disdained, tolerated, and championed forms of copying, including biting, beat jacking, ghosting, battle quoting, homage quoting, and riff quoting, where only biting (“the appropriation of another’s lyrics and passing off such lyrics as one’s own without the authorization of the primary lyricist”) and beat jacking (“also known as beat biting, [it] is the non-lyrical equivalent of biting”) result in internal discipline, namely, “the end of the biter’s career as a serious artist within the community.”33 Jafa’s appropriations seem to fall squarely within the tolerated or encouraged forms of copying. Rather than community-based opprobrium or the initiation of a surefire lawsuit by Kanye West for the unlicensed use of “Ultralight Beam,” Jafa was immediately commissioned to direct music videos within the industry, including Jay-Z’s “4:44” (2017) and West’s “Wash Us in the Blood” (2020). Scorsese has, to my knowledge, remained silent on BG, but Schrader openly praised it.34

Community norms encourage rights holders and affected parties (like West or Schrader) to see homage where others might see infringement. Less famous rights holders likely recognize the artistic and critical importance of Jafa’s appropriation, diminishing the likelihood of a lawsuit. Finally, corporations that zealously protect their intellectual property, like Getty Images, surely concede the substantive commentary or critique in Jafa’s video, which would render potential lawsuits not only unseemly, but also unsuccessful (based on a fair use defense). In Jafa’s videos, we find a rare alignment of strong art, community norms, and a solid legal basis in contemporary appropriation.

VI. The Evasive Racism of Taxi Driver

BG’s power is bound up with the evasiveness of Taxi Driver’s racism. As Amy Taubin argues in her monograph on the film: “Racism is the problem with which Taxi Driver never quite comes to terms. And this evasion prevents it from being a truly great film, while allowing it a popularity that it otherwise would not have achieved.”35 Even for screenplay writer Paul Schrader, the matter is complex: “There’s no doubt,” he says, “that Travis is a racist. He’s full of anger and he directs his anger at people who are just a little lower on the totem pole than he is. But there’s a difference between making a movie about a racist and making a racist movie.”36 Jafa registers this ambivalence but ultimately makes the contrary argument:

Aruna D’Souza: So, in your opinion, is Taxi Driver a racist film?

Arthur Jafa: I know there’s an argument, is this a film about a racist p. 75 or a racist film? Racism is just part of the paradigm and the structure will lead you to it. Unless you are very consciously trying to counter those tropes, you’ll inevitably find yourself in that place.

With [BG], it’s like I’m polishing a troubled artifact. Part of the (perhaps waning) superpower of Black people is our ability to see stuff for what it is, not to be in self-imposed denial about it. I’m seeing Taxi Driver for what it is.37

Two crucial points. First, “seeing stuff for what it is” is affective intuition, the product of trained judgment. Jafa’s BG must be viewed as an effort to buttress the waning “superpower of Black people” and also to extend it to non-Black people. This is a core achievement of BG and I will return to it in the final section. Second, Jafa’s slight hedge—despite the emphatic certainty of his conclusion—is instructive and essential. Among Jafa’s explicit arguments is that Travis Bickle, the eponymous taxi driver in Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, is cut from the same cloth as white sociopaths like Arthur Bremer, John Hinckley Jr., and Dylann Roof, the white supremacist who walked into a Black church in Charleston in 2015 and killed nine parishioners.38 (Roof is also a central protagonist in Jafa’s White Album.) But if Jafa simply wanted to call out Travis Bickle’s character, a tweet would have sufficed. Jafa was after something more. And for that, the racism in Taxi Driver needed to be much more complex than that in, say, Birth of a Nation (1915).

Taxi Driver has generally been received in terms of white sociopathy of the incel variety, rather than racism, per se. Travis first targets a (white) presidential candidate. The script was inspired, at least in part, by Arthur Bremer’s attempted assassination of presidential candidate George Wallace in 1972. And the film would inspire John Hinckley Jr.’s assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan in 1981. African Americans are not the obvious targets in the film. And yet, as Taubin reflects, “Travis’s racism is evident to anyone who looks at the film carefully.”39 Indeed, as recently elucidated in a New York Times profile of Hinckley and his affinities for white suprematism and the American Nazi Party, among other racist affiliations: “it was as though he had read between the lines of [Travis] Bickle’s fury and contempt and decoded, without sensitivity to the film’s complexities, the racial animosity that lay within it.”40

Much of the worst racism in Taxi Driver is complex, such as Scorsese’s cameo, where he plays a husband cuckolded by his wife with a Black lover. As Jafa notes, the character played by Scorsese “was nominally racist. Meaning it was contextually driven.”41 More subtle still—at least in the original film—is an exchange and a glance among cabbies in a diner. (This is the only scene incorporated unchanged into BG.) The cabbies, including one p. 76 Black cabbie, are discussing rough customers and the need to carry a weapon in self-defense. In the midst of this conversation, Travis throws a sidelong glance at a pair of figures whom Jafa identifies as real-world Black pimps (in contradistinction to the unconvincing white pimp played by Harvey Keitel). Scorsese’s camera moves slowly over the pair as they sit in their booth, a shot that provides a marked emphasis for a viewer. When Jafa takes up this scene, however, he makes clear the string of associations that implies the murder of the Black pimp otherwise suppressed in the film: a jump cut from the diner scene directly to the murder of the Black pimp in his version of the movie. Jafa thus draws a line from the real-world Black pimps in the diner to the murder of the unredacted Black pimp in BG; the name of that line is virulent white supremacy. It is a line muddied in the original film.

In Jafa’s 2003 essay, “My Black Death,” which he’s described as his manifesto, he ventures a sprawling history of African and Black influences on Western art from Picasso and Cubism through Jackson Pollock and beyond. He concludes with several deliriously striking readings of Blackness in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1969), Star Wars (1977), and Alien (1979). These readings—not backed by the same archival evidence of Schrader’s original screenplay—do not merely tackle overtly racist films. Nor does Jafa dismiss the works or directors he criticizes.42 Jafa is after evasive racism. And its counterfactual alterities.

VII. Counterfactual Revelry

Jafa’s most dramatic change—and the only fundamental change to the narrative beyond the reversions to Black characters—is sandwiched between two extended close-ups of Scar, the Black pimp. In this variation, the third chamber of Travis’s gun is not empty and he successfully blows out his brains. The force of the blow carries him off-screen and we are treated to a final tableau without the white menace. At the end of this shot, we do not hear the melodramatic chords that signal the entrance of the police, but rather, the first chords of the Jackson 5’s 1975 Motown hit “All I Do Is Think of You,” which provides the backdrop to the Black pimp’s counterfactual revelry. For a blissful (if still shocking) 90 seconds, Travis is dead, Scar revels, and white supremacist mania yields to Black respite. It won’t last, of course. It can’t. Not in Jafa’s pessimistic world. But it’s there. And if you reduce the work to the exposure of racism elaborated in its first few minutes, you’d miss it entirely.

The shoot-up scene in Scorsese’s Taxi Driver is notoriously violent. BG exposes us to Scorsese’s violence, amplified by its now explicit racism, over and over again. The slight variations ensure that we remain engaged with its gory details. Seventy-three minutes of this racist carnage would be unbearable. p. 77 The lulls are lifelines. They are reparative moments in a video shot through with paranoia, based on a film suffused with paranoia.43 They are moments of grace. As Jafa has remarked: “Having Scar listening to Stevie Wonder— I hate to say it—humanizes a type of person of whom most people have a very narrow understanding.”44 (Schrader has said roughly the same about his treatment of Travis Bickle.45) Taxi Driver includes a creepy scene—not in the original script—of Sport (the white pimp played by Harvey Keitel) holding Iris (Jodie Foster) in a tender and abusive embrace, exerting physical and psychological control over his twelve-year-old lover and prostitute. But in so much as the tenderness is a performance, we gain little insight into his actual psyche. By contrast, BG provides three distinct vignettes of Scar (the Black pimp), each of which provides a window, cloudy rather than transparent, into the character’s inner life.

The first close-up lingers on Scar for over five minutes, nearly the duration of Stevie Wonder’s “As.” Scar alternatingly sings along, loses himself in the music, and scans his environment—Travis Bickle was hardly the only threat facing Black pimps in 1976 New York City. Stevie Wonder’s music continues as Travis enters the brothel, shoots the fingers off the bouncer’s hand, and exchanges fire with Scar; it ends just in time for Travis to deliver the execution-style final shot to the head of Scar.

The third extended close-up, set to the Jackson 5’s “All I Do Is Think of You,” offers a similar, if briefer, respite. We know how this ends. Figure 12 Arthur Jafa. BG, 2024. Installation photograph at Gladstone Gallery, 2024. © Arthur Jafa. Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, and Sprüth Magers.

Arthur Jafa. BG, 2024. Installation photograph at Gladstone Gallery, 2024. © Arthur Jafa. Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, and Sprüth Magers.

It is in the second extended close-up, roughly three-and-a-half minutes long, where Scar’s inner life is put into words. Wordy essays run the risk of privileging erudite words, a bias that would do Scar and BG no favors. For it’s precisely the protracted attention to Scar’s introspective, musical revelry that is the most unthinkable intervention into Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. Racialized fears precluded the possibility of a Black pimp; populating such a persona with a complex inner life was simply unthinkable in mainstream p. 78 cinema circa 1976. (Audiences would have to wait two years—and much longer, for widespread distribution—to see comparably contemplative inwardness afforded a Black character, in Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep, 1978, itself a notable exception in twentieth-century cinema.46) Nonetheless, Scar’s poetic and disjointed soliloquy is redolent, with references to W.E.B Du Bois, Killer of Sheep, Stevie Wonder, and haunting reflections that cannot be pinned down precisely (“… I ain’t no hustler baby … just a dead black star … killa of sheep and dreams …”). Amidst the dense web of reflections and allusions comes a single line that encapsulates the predicament that must have instigated the entire video: “I’ve seen things … y’all wouldn’t believe … and did not.”

VIII. Seeing Is Believing?

It is not hard to recognize white supremacy in Dylann Roof. What is hard to capture—and this is where BG succeeds so brilliantly—is the capacity not just to know the undercover racism of Taxi Driver, but to see it. This is not our first go-around with seeing is believing. Painfully few years ago, phone cameras and social media—including clips featured in Love Is the Message—made racist police brutality visible. Vanishingly few African Americans were shocked by the videos of police brutality. Too many white Americans did not believe it previously because they did not see it. As soon as smartphone cameras became the norm, the normalcy of racialized police violence became visible. Smartphone cameras and body cams provided the visual evidence of systemic racism.

When Jafa reflected on the origins of Love Is the Message, he turned to the Rodney King video: “Rodney King was only the beginning. Those witnesses just happened to have video cameras, not cell phones, but that’s the beginning of citizen-documented video, verification that the things we’re describing are not figments of our imagination, these things are real. And they’re not exaggerations.”47

The Rodney King video is cruelly instructive. Figure 13 Rodney King video, March 3, 1991. Video still. As Judith Butler argued shortly after the trial, even the video was not enough:

Rodney King video, March 3, 1991. Video still. As Judith Butler argued shortly after the trial, even the video was not enough:

The video [shown by the lawyers defending the police officers] shows a man being brutally beaten, repeatedly, and without visible resistance; and so the question is, How could this video be used as evidence that the body being beaten was itself the source of danger, the threat of violence, and, further, that the beaten body of Rodney King bore an intention to injure, and to injure precisely those police who either wielded the baton against him or stood encircling him? In the Simi Valley courtroom, what many took to be incontrovertible evidence against the police p. 79 was presented instead to establish police vulnerability, that is, to support the contention that Rodney King was endangering the police.48

Elizabeth Alexander, in her essential account of the video and its reception, is even more precise and anticipates the power and import of Jafa’s subtle manipulation of frame rates in Love Is the Message and other works:

The [defense] lawyers also slowed down the famous videotape so that it no longer existed in “real time” but rather in a slow dance of stylized movement that could as easily be read as self-defense or as a threat. The slowed-down tape recorded neither the sound of falling blows nor the screams from King and the witnesses. The movement existed frame by frame rather than in real time.49

The video was not enough. Incontrovertible evidence was not enough. Seeing was not believing. Butler continues: “to the extent that there is a racist organization and disposition of the visible, it will work to circumscribe what qualifies as visual evidence, such that it is in some cases impossible to establish the ‘truth’ of racist brutality through recourse to visual evidence.”50 Butler terms this condition “white paranoia,” to which BG responds not with more evidence but with a productive form of antiracist paranoia.

In a famous 1970 essay, Joseph White, the “father of Black psychology,” argued:

Part of the objective condition of black people in this society is that of a paranoid condition. There is and has been unwarranted, systematic persecution and exploitation of black people as a group. A black person who is not suspicious of the white culture is pathologically denying certain objective and basic realities of the black experience.51

Jafa recognizes “the value of healthy black paranoia” and directs it far beyond Taxi Driver, whose covert racism is evidenced indisputably in p. 80 Schrader’s original script.52 BG does not provide evidence. It deals in affect and intuition. Sitting in a cinema in 1976, Jafa had no archival evidence of the suppressed Blackness of Taxi Driver’s pimp and brothel denizens. But he was able to intuit it. And, as he writes in his essay “My Black Death,” he saw it as well in 2001: A Space Odyssey, Star Wars, Alien, Marcel Duchamp, Jackson Pollock, and other cultural touchstones for which less direct evidence survives of suppressed Blackness. Jafa’s intuition carries a paranoic quality. But as the adage goes: Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t after you.

The adage applies to both Scorsese’s Taxi Driver and Jafa’s BG. Travis’s paranoia is indissociable from his racism. Jafa’s paranoia correctly clued him into Travis’s racism and the suppressed Blackness of the pimp and other brothel habitués. Jafa’s close readings of 2001: A Space Odyssey, Star Wars, and Alien, however, lack the archival evidence that supports his intuition about Taxi Driver. And the paranoic intuition muddies the reading of Taxi Driver as well. A consummate product of Scorsese’s modernist period, Taxi Driver inhabits Travis’s paranoia to such an extent that it troubles the reliability not only of his character but also of the film itself. Nowhere is this more pronounced than in the film’s coda. A camera pans the walls of Travis’s apartment, now decorated with newspaper clippings of his heroism and recovery. It lingers on the letter written by Iris’s parents and read, in voiceover, by Iris’s father, thanking him from the bottom of their hearts for saving their daughter. Soon enough Travis is back behind the wheel of his taxi, driving Betsy (Cybill Shepherd), the love interest who spurned him but now reverently asks: “I read about you in the papers. How are you?” Travis, the chaste hero, refuses to accept payment for the ride, dismisses her with a “so long,” and rides off in glory. The preposterous happy ending—sullied only by a paranoid double take indicative of a physical recovery without a mental correlate—is impossible to accept at face value. The final scenes register as the megalomaniacal dream of a racist vigilante dying on a bloodstained cathouse couch. Yet the filmmaking does not distinguish between the final shoot-up and an ending that reads as ludicrous and delusional. By the time the credits roll, we can no longer trust what we see.

Paranoia in BG operates differently. BG diverges from the original film in order to be more faithful to the original script and the social circumstances depicted therein. What’s more, the most “paranoid” contention in BG—namely, that Travis’s racism was repressed by the director/writer/studio for fear of racial backlash—is unquestionably true. In these respects, there is nothing paranoid in BG and, unlike Taxi Driver, it largely can be taken at face value. And yet just as Travis’s paranoia ultimately infects the entire film, so p. 81 too BG’s “paranoid” (yet factual) premise cannot be limited to Taxi Driver and its demonstrably repressed racism. To experience BG is to enter—or at least entertain—a world in which racism is visible in nearly every image.

It is also a world in which every image can be doctored. Today, there is more reason than ever to be paranoid. Jafa’s dream to remake Taxi Driver was hatched in a cinema in 1976. But it remained latent until he saw deepfakes circulating on social media.53 Generative AI was not yet advanced enough to forgo actors (even if Jafa had wanted to do so), but the recourse to traditional cinematography and special effects in no way diminishes Jafa’s engagement with AI. Just as interwar avant-garde artists explored a “cinematic imaginary” through photomontage, cameraless photography, even painting and sculpture—but often without recourse to projected film—so too Jafa confronts generative AI without relying on cutting-edge AI technologies.54 The manipulation of history afforded by AI technologies—as much as the technologies themselves—is the epistemological condition of possibility for BG.

Fabian Offert opens a recent (and already partially outdated) essay on the concepts of history implicit in the deep neural networks (or “foundation models”) that powered image generation programs such DALL-E 2. He asserts and asks the following:

Any sufficiently complex technical object that exists in time has, in a sense, a concept of history: a way that the past continues to exist for it, with contingencies and omissions specific to its place and role in the world. This essay asks: what is the concept of history that emerges from a specific class of technical objects that have come to dominate the field of artificial intelligence, so-called “foundation models”?55

Offert argues for a contorted historical-specificity of mediated images that will likely remain a default condition of most AI-generative models as they regurgitate versions of the data they are fed. Ask for a photograph of Frederick Douglass, without specifying any further details, and DALL-E 3 (incorporated into ChatGPT-4o) spits out images that mimic the daguerreotypes or collodion-based photographs in which he was most often memorialized. Ask for photographs of Stevie Wonder and, voila, the images are now infused with color.

Jafa categorically rejected the artificial sheen of generative AI. All the un- redacted Black characters were newly filmed with real actors. And the digital editing was realized by BUF, a visual effects industry leader that also works with the Wachowski siblings (and their “bullet time effect” seen in The Matrix), Christopher Nolan, Michel Gondry, Wong Kar-wai, and others; BUF also rendered the imagery for Jafa’s 2021 audiovisual installation AGHDRA. p. 82 The digital manipulation in BG is best situated in the long history of Hollywood special effects and the longer history of photographic manipulation.56 But Hollywood is unequivocally turning to AI for wide-ranging effects, special and mundane. And in so much as ever more advanced AI tools are readily available to everyday consumers, the sea change is hardly limited to Hollywood. In other words, AI-enabled deepfakes not only were the trigger for Jafa’s realization that his decades-old dream was suddenly viable, but also are constitutive of the visual culture into which BG intervenes. Accordingly, BG sits uncomfortably between a 1976 cinematic intuition and 2024 technologies that enable the manipulation of images at a scale and speed long feared but never before realized. The disconnect and discomfort are productive.

We are all familiar with AI-generated images of the pope in a puffer jacket and the video where Jordan Peele turns Barack Obama into a human puppet. These are child’s play compared to the weaponized deepfake pornography and other AI-generated images well in excess of Travis Bickle’s seedy Times Square. With the Elon Musk–backed Grok churning out images without real guardrails, deepfakes, mundane or hazardous, are now commonplaces. Deep- fakes are most immediately injurious in the present; they are most pernicious when directed toward the past. This is the degraded reality that confronts us now and in the indefinite future. What Jafa did to Taxi Driver will be done thousands more times with vastly less expense, effort, and care. But just as the recent omnipresence of found-footage music collages—and Jafa’s videos for marquee music artists—only enhances the power of Love Is the Message, so too the importance of Jafa’s BG is only heightened by the prospect of an ocean of cheap imitations in which it will likely be engulfed. Counterfactual visual evidence is now part of our lives. Seeing is no longer believing, in the old sense. Mechanical objectivity has yielded to trained judgment in both the human reception of images and their nonhuman creation. In this regard, the watershed that separates Love Is the Message and BG is epochal. Love Is the Message was anchored in ascendant camera phones, online videos, social media, and the newfound opportunities to capture, disseminate, and arrange affective units that doubled as visual evidence—and visual evidence that doubled as affective units. BG is anchored in ascendant AI technologies whose affective atmospheres or vibes carry meanings too amorphous to ever serve as evidence.57 Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death is among the last great works of affective montage of the cinematic era. BG is among the first great works of trained intuition in the age of AI.

BG does not provide new evidence of Hollywood racism. Instead, it stimulates the capacity to see racism even when it goes undercover, as in Taxi p. 83 Driver, and even when its presence is less certain. It’s not evidentiary but intuitive. BG stimulates in its viewers a paranoic vision shot through with antiracism. For once you are trained on Jafa’s many unredacted versions of Taxi Driver, you can never see the original the same. This isn’t the seeing-is-believing evidence of a court of law. This is intuitive seeing-is-believing in the age of AI. As we confront a deluge of deepfakes, Arthur Jafa’s BG creates the conditions for countervailing deep truths.

Acknowledgments

This essay builds on a talk given at e-flux at the invitation of Lukas Brasiskis. I thank him and the audience for the opportunity and feedback, and Dan Morgan, Hal Foster, Claudia Breger, Weihong Bao, Xiyin Tang, and several anonymous peer-reviewers for their close critical readings. The essay took its final form in dialogue with the editors of Grey Room, current and future, and is dedicated to them.