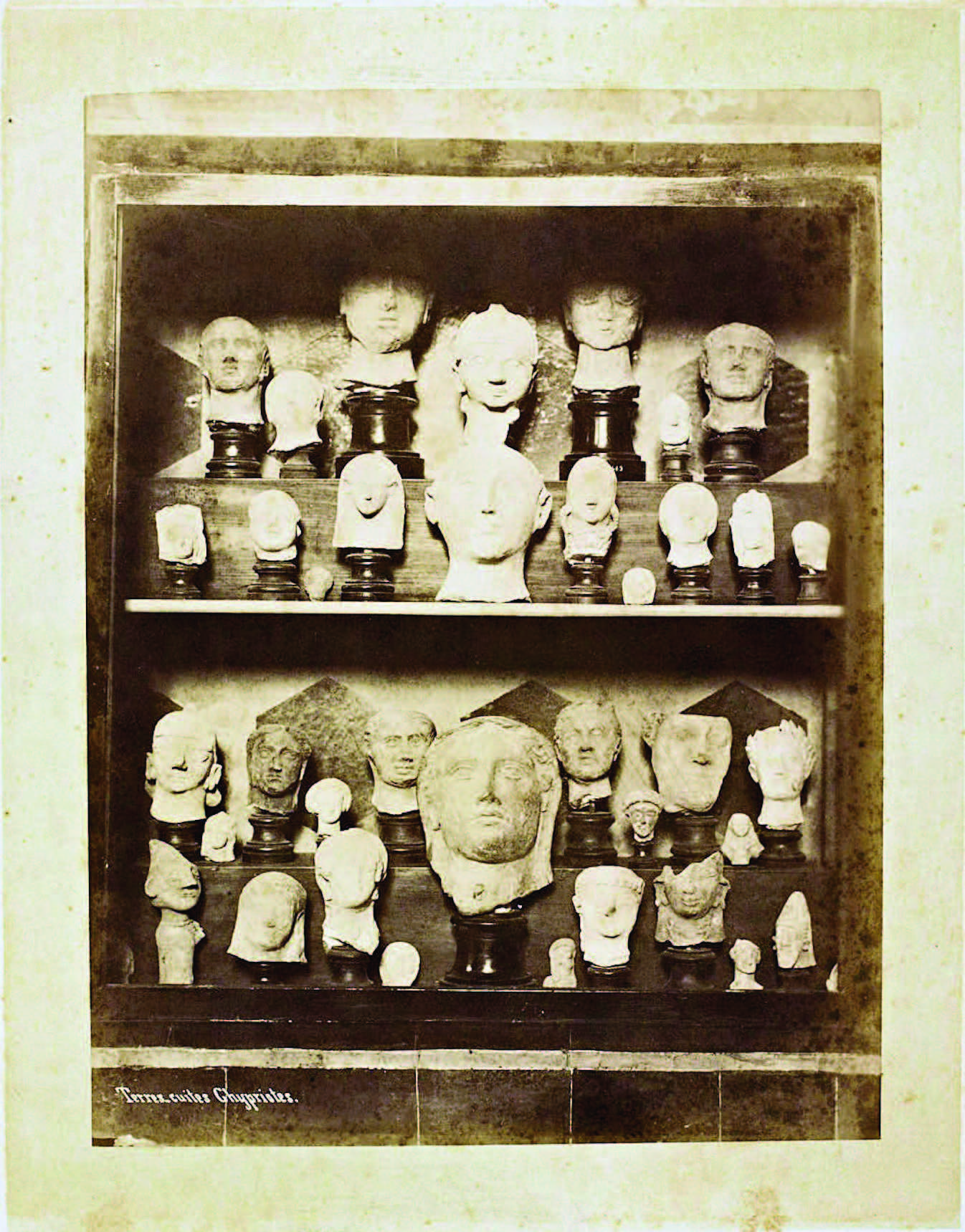

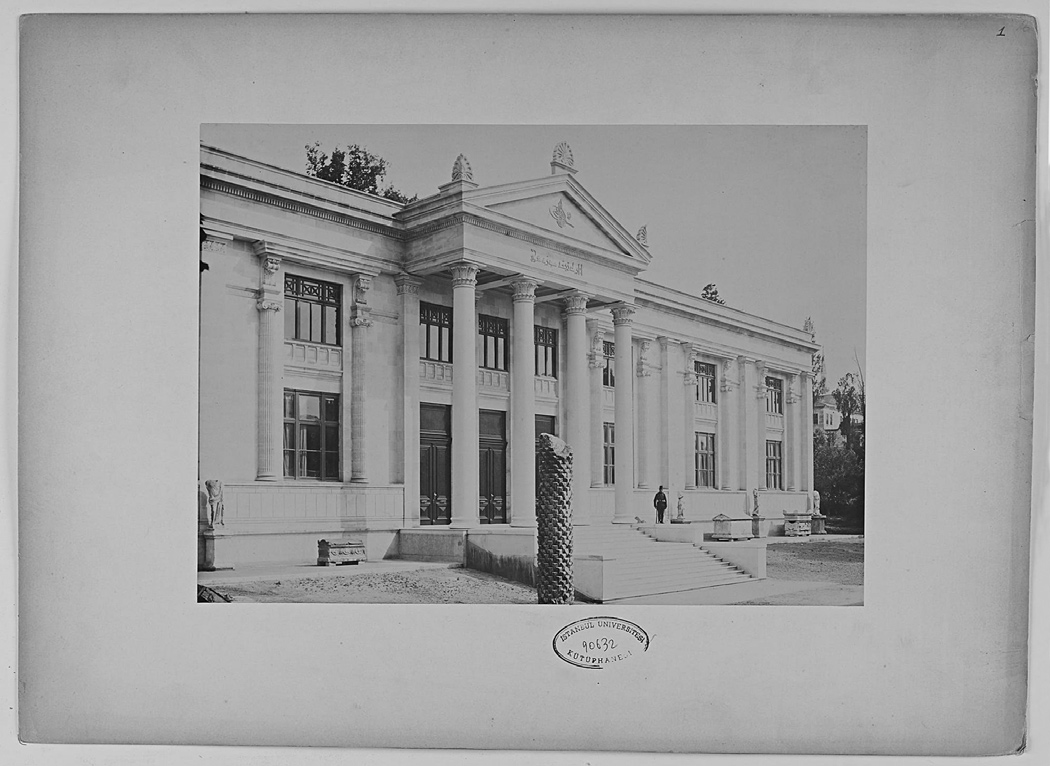

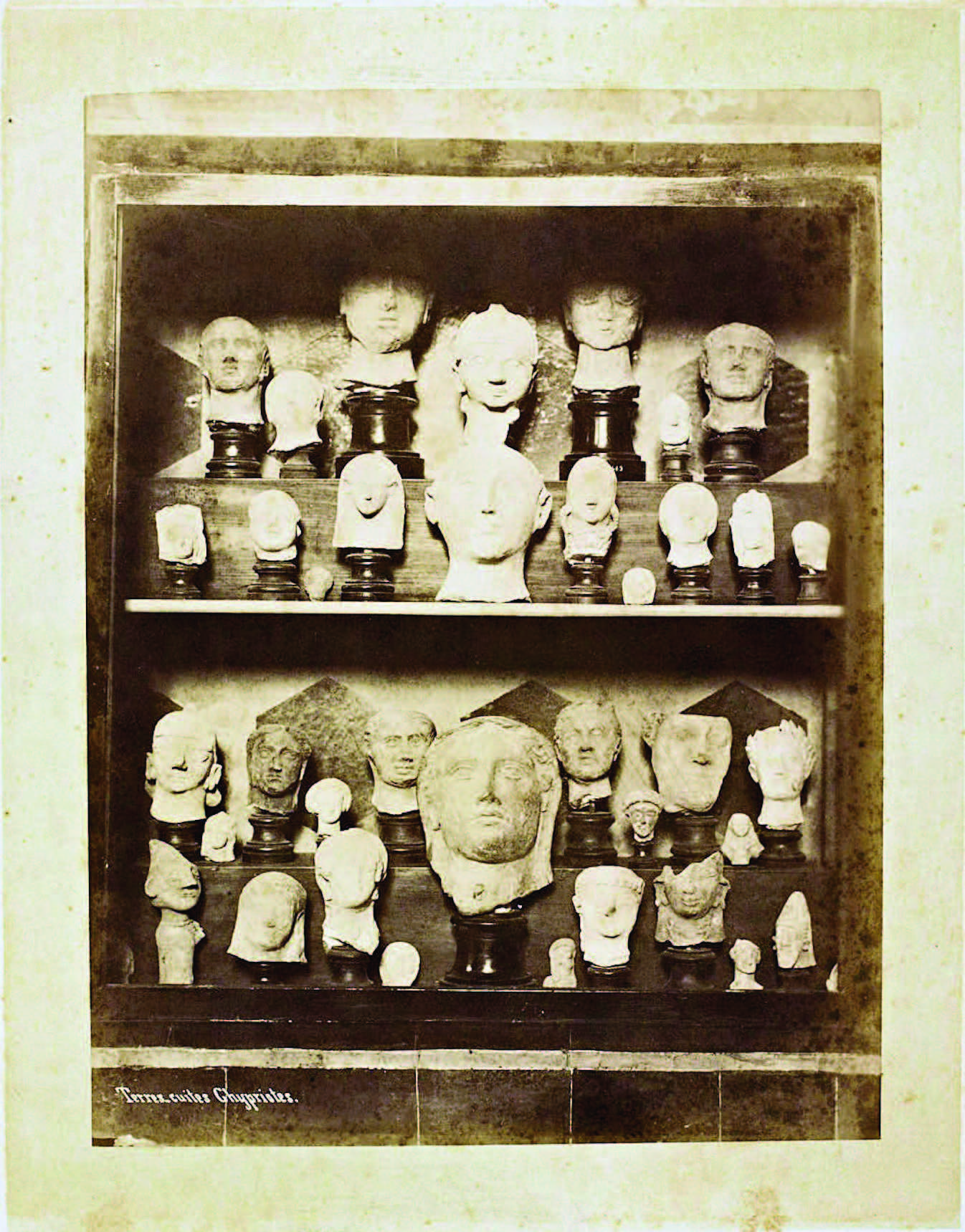

Figure 1 Pascal Sébah, Terres-cuites Chypriotes (Cypriot terracotta). Abdülhamid II Photography Collection, Rare Works Library, Istanbul University. Thirty-six terracotta heads appear in an image captured sometime in the 1880s as part of a series documenting the collection of the Imperial Museum (Müze-i Hümayun) in Istanbul.1 The display combines Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Greek, and Roman heads of various sizes, arranged on four wooden shelves. Unearthed in Cyprus, the heads likely entered the collection at least a decade before the British took over the administration of the island in 1878, while it stayed under nominal Ottoman sovereignty.2 Together, the artifacts visually conjured a range of ancient civilizations whose remains were buried mostly under Ottoman soil.

Pascal Sébah, Terres-cuites Chypriotes (Cypriot terracotta). Abdülhamid II Photography Collection, Rare Works Library, Istanbul University. Thirty-six terracotta heads appear in an image captured sometime in the 1880s as part of a series documenting the collection of the Imperial Museum (Müze-i Hümayun) in Istanbul.1 The display combines Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Greek, and Roman heads of various sizes, arranged on four wooden shelves. Unearthed in Cyprus, the heads likely entered the collection at least a decade before the British took over the administration of the island in 1878, while it stayed under nominal Ottoman sovereignty.2 Together, the artifacts visually conjured a range of ancient civilizations whose remains were buried mostly under Ottoman soil.

While the image caption, “Cypriot terracotta,” may suggest that the common denominator of the artifacts was simply their shared material or provenance, the display stands out because of its resonance with the legal definition of antiquities in the empire at the time. The 1884 Ottoman law of antiquities defined antiquities as “all of the artifacts left by the ancient peoples (ahâlî-i kadîme) who inhabited the lands that constituted the Ottoman Empire” and offered an extensive list of objects that counted as such: temples, theaters, bridges, aqueducts, obelisks, corpses, and mausolea, to name a few.3 An earlier version of the law had defined artifacts in terms of their mobility (transportable or not).4 Yet this version extended a claim to artifacts via their vastly different owners, implicitly declaring ancient Greeks, Egyptians, Babylonians, Phoenicians, Assyrians, and others as former Ottoman residents.

This designation marked not only a change in the understanding of artifacts but also a transformation in Ottoman technologies of governing difference. In the closing decades of the nineteenth century, looming threats of European incursion in the empire’s territories along with pressures of internal rebellions exacerbated anxieties about Ottoman sovereignty. This propelled a shift in governance from an imperial mode crafted to manage a multiethnic, multireligious, and multilingual populace through heterogenous administrative arrangements (known as the millet system), toward an imperial nation-state mode that aspired to standardize the administration of a community of nominally equal p. 18 citizens within a bounded territory.5

Consequently, Ottoman reformers faced a major conceptual challenge: how to reconcile the universality of new administrative categories and rules with the highly particular nature of existing social relations? In a word, for the central government known as the Sublime Porte to tighten its grip over remote provinces in the imperial nation-state mode, it needed rules and categories of governance that were valid always and everywhere.6 The Porte thus legislated laws enforceable across the empire, intruding into the internal affairs of religious communities and other groups such as tribes. It also invented new categories to regulate the relationship between the government and these subjects, the most significant of which was universal imperial citizenship. By equalizing Ottoman subjects before the law this new category was meant, at least in theory, to overwrite previous legal categories based on differentiated ways of organizing collective life. Here, citizenship was less about granting subjects political rights as it is typically understood within the liberal paradigm; it was about asserting sovereignty over imperial subjects, and by extension, their property. This was especially true as property ownership undergirded the very definition of citizenship.7 While the ethos of equalizing Muslims and non-Muslims before the law permeated an earlier set of reforms known as the Tanzimat, or reorganization (1839–1876), it was not until the final decades of the century that it was enshrined in law.

The 1884 law of antiquities was part and parcel of this universalizing drive. Its scope encompassed the empire, and its claim over antiquities as the property of the state was made through interpellating “ancient peoples” as former Ottoman residents, thus mirroring the Ottoman government’s claim to sovereignty over the possessions of its newly minted citizens. Predictably, what transpired on the ground was more complicated. Scholars have detailed the many instances in which the law of antiquities was bent, resisted, or outright ignored. Ottoman bureaucrats found ways to export archaeological objects before documenting them, German and British officials petitioned for exceptions to acquire antiquities owned by the state, and the sultan used artifacts as diplomatic gifts to cultivate political alliances.8 One historian described this dynamic as “dialectics of law and infringement.”9 In placing the letter of law and its breach at opposite ends of a duality, such framework posits the state and its administrative categories and rules as disembodied tools, isolated from the social reality they govern.10 By exploring how the conceptual problem of reconciling universals and particulars unfolded historically in the empire, I propose a different lens on the workings of the administrative state. Rather than taking the abstractions of the state and the concreteness of society as givens, I ask how p. 19 their distinction has historically come to be.11

In what follows, I examine how the question of universals came to occupy Ottoman reformers in the late nineteenth century in several realms of life at once: science, legislation, and aesthetics. While the problem was articulated in each realm differently, all articulations were haunted by a concern with Ottoman sovereignty over land and subjects. One influential figure that traversed these realms was the Armenian bureaucrat Sakızlı Ohannes Efendi (1836–1912). Known today as the foremost proponent of economic liberalism in the empire, Ohannes also delivered the first lectures on aesthetics at the School of Fine Arts (Sanâyi-i Nefîse Mektebi) in Istanbul, and had a long tenure in the Ottoman bureaucracy. His insights are thus uniquely revealing of the status of universals in late Ottoman reform-minded pursuits. Taking Ohannes’s writing on aesthetics and political economy as a point of departure, I examine how the tension between universals and particulars was mediated in two particularly revealing sites often studied in isolation. The first is Darülfünûn (House of Sciences), a monumental building repurposed in 1877 from a site for teaching the universals of the natural sciences at the first Ottoman university, to one for legislating positive universal laws as the first Ottoman parliament. And the second is the Imperial Museum, where rather than compiling trophies of recent conquests like its European counterparts, the universalist idiom of neoclassicism was deployed to stabilize a precarious territorial sovereignty. What emerges is a sketch of a new governmental reason which, even as it was vested in the universality of rules of regulations, did not annihilate but reconstituted particulars.

Universals

In the introduction to his 1880 book, Mebâdi-i Ilm-i Servet-i Milel (Principles of the science of the wealth of nations), which heralded sustained publications on political economy in the empire, Ohannes states that “the science of wealth does not invent [ihtirâ’ değil], but only discovers and proves the natural laws [kavânîn-i tabiiyye] that govern the material well-being of human society.”12 In another statement, similarly reminiscent of the universalist zeal of his European counterparts, Ohannes maintains that “human society, like all other composite bodies (ecsâm-ı mürekkebe), is subject to certain natural laws, and in compliance with these laws it either flourishes or perishes.”13 Yet he adds that while it would have been convenient to simply translate one of the numerous existing works on political economy, these works remain inadequate to the particular conditions of the empire, as their authors had written them with an eye to the needs of their respective nations. How to explain, then, Ohannes’s insistence that those particular p. 20 conditions demand their own mode of theorization, while in the same breath, invoking the most universalist trope of them all—natural law? Figure 2 Gaspare Fossati, A Panorama of Istanbul foregrounding the Darülfünûn building, and taken from one of Aya Sofia’s Minarets, 1852. From Aya Sofia, Constantinople, as recently restored by order of H.M. the Sultan Abdul Medjid, plate 20. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, DC

Gaspare Fossati, A Panorama of Istanbul foregrounding the Darülfünûn building, and taken from one of Aya Sofia’s Minarets, 1852. From Aya Sofia, Constantinople, as recently restored by order of H.M. the Sultan Abdul Medjid, plate 20. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, DC

The idea of nature as a legislator of sorts had started shaping the meaning of being rule-governed in the empire across the natural sciences, political theory, and jurisprudence since the 1860s. One important vehicle for this influence was the Journal of Sciences (Mecmûa-i Fünûn) where, prior to publishing his own book on political economy, Ohannes published serialized and abridged Ottoman Turkish translations of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations. Appearing intermittently between 1860 and 1882, the journal was the publishing arm of the Ottoman Learned Society (Cemiyet-i İlmiye-i Osmâniye), the first civil association created for the advancement of sciences in the empire.14 The journal’s pages combined Ohannes’s translations of Smith with titles such as “An Introduction to Geology” and “The Essence, Properties and Types of Water.” The contributing authors wrote in a self-consciously plain language about regularities in nature that were supposed to hold, under a specific set of conditions, always and everywhere.

If the journal was where the reading public in the empire could learn the latest in the sciences of nature and government, the building of the Ottoman university, Darülfünûn, was the primary site where students of these sciences met. From the outset, Ottoman educational reformers conceived the university as an institution that aspired to nothing less than the “perfection of humanity” (kemâlât-ı insâniyye).15 To design the building in which this lofty goal would be achieved, they selected the Swiss architect Gaspare Fossati (1809–1883), who by then had many state buildings under his belt. Construction began in 1846 but was plagued with many delays for reasons including irregular payments, the outbreak of the Crimean war, and uncertainty about the program. The building remained under construction for over two decades.16

Historians have written the story of the building as one of divergent p. 21 architectural and institutional visions.17 While the idea that a monumental building would serve educational reforms generated consensus, the details of its program did not. In an ironic culmination of events, the building whose site selection and design were shaped by considerations for future expansion was deemed too large for its purpose once completed, and the university was moved to more modest premises.18

Yet Darülfünûn was not just an artifact of inflated ambition and myopic planning. It can, in fact, be read as an apt monument to mid-nineteenth century Ottoman reforms—except for reasons that have nothing to do with its visible location, ornate fac¸ades, or commanding scale. Rather, as a primary site for deliberating universals, the building materialized a central conceptual problem of Ottoman reform. Inaugurated twice to much fanfare within a little over a decade, each inauguration of the building, as I will show next, foregrounded universals of a different kind. In the first inauguration, scholars and statesmen lectured on natural laws and performed scientific demonstrations to a mix of learned and lay audiences. In the second, legislators deliberated universal laws of the judicial variety.

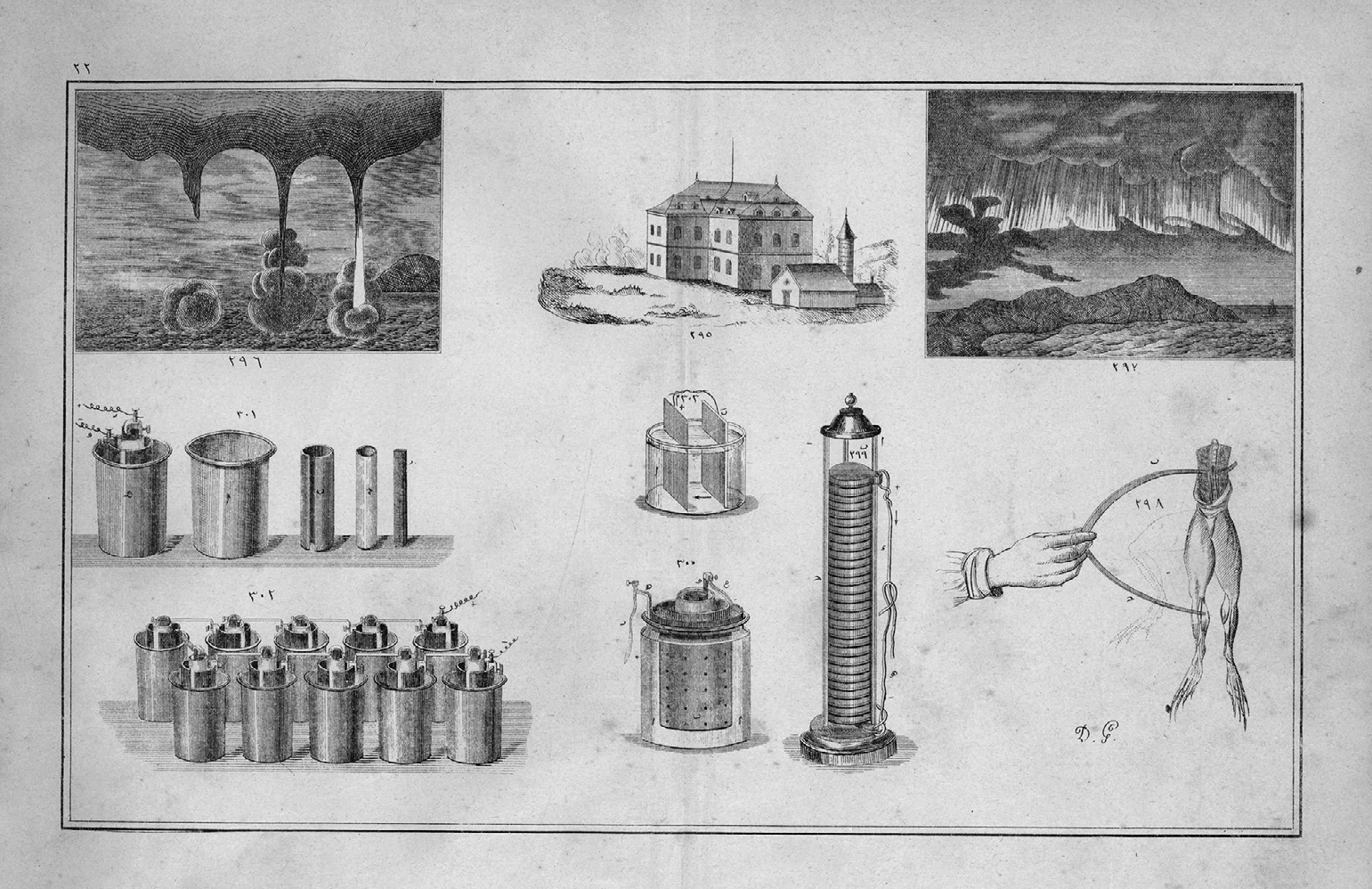

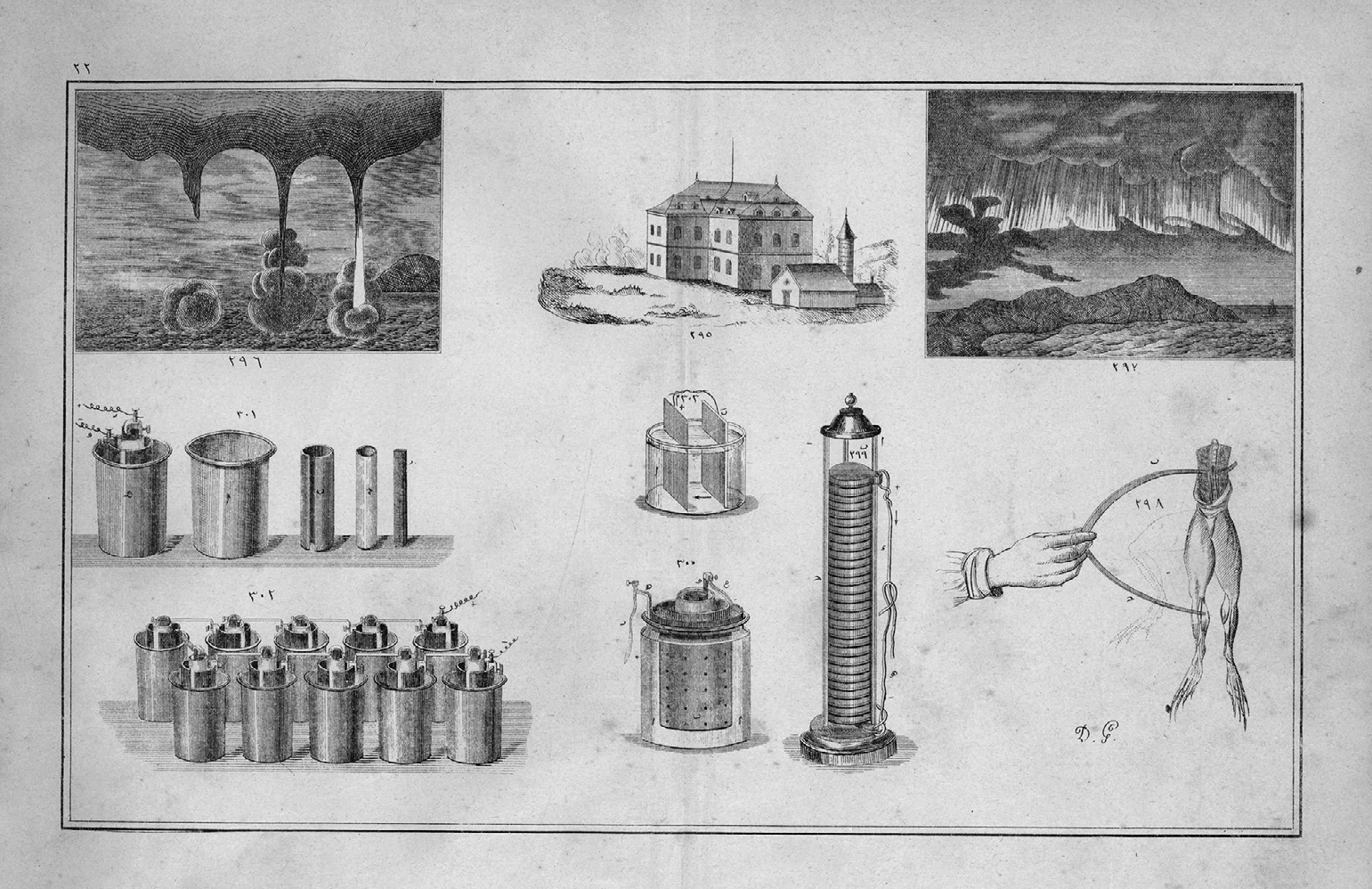

In 1863, even before construction was complete, an official decision was made to inaugurate Darülfünûn as a university.19 This first inauguration took the form of a series of public lectures that were enthusiastically promoted by the Journal of Sciences. An early announcement in the journal emphasized the necessity of witnessing experiments, and assured its readers that simple terms would be used whenever possible so that “everybody could understand,” including all classes of imperial subjects—students, civil servants, and men of arts and crafts.20 Mehmed Emin Derviș Pasha (1817–1879), the director of imperial mines, delivered the first lecture of which the journal provided an especially vivid account. After covering some of the basics of physics and chemistry to three hundred attendees, Dervis¸ Pasha performed experiments, likely using instruments he detailed in his physics textbook. These were

curious phenomena, and the majority of the audience who were seeing such things for the first time in their lives were flabbergasted. Especially the experiments on electrical force where sparks of fire emerged from special tools, and when said force was transmitted into a man’s body via a thin wire, his hand or whatever part of his body that the wire touched emitted blue sparks, and where, thanks to certain chemical compounds, an iron wire became incandescent and fiery like an inflammable substance, left them in astonishment.21

p. 22 In the following weeks, several other statesmen took the stage to lecture and perform demonstrations in various topics in the natural sciences. Chief of the Central Court (Meclis-i Tahkîk) and Chief Physician Salih Efendi lectured on the biological sciences; Head of the Military Academy Safvet Pasha lectured on the laws of gravity while Dervis¸ Pasha was away on a trip; and court astrologer, Osman Saip Efendi, who was a member of the ulema (scholars of Islamic doctrine and law) lectured on astronomy, to name a few examples.22 Figure 3 Illustrations explaining electric current. From Usûl-i Hikmet-i Tabiiye by Mehmed Emin Derviş Paşa. Istanbul, 1870.

Illustrations explaining electric current. From Usûl-i Hikmet-i Tabiiye by Mehmed Emin Derviş Paşa. Istanbul, 1870.

That it was predominantly state bureaucrats who performed these demonstrations—often tackling natural sciences in which they had little expertise—drew explanations from both contemporaneous observers and historians. Münif Pasha, the journal’s editor, reasoned in an article on the lectures that the days when states could be run by the ignorant and incompetent were gone. State positions ought instead to be granted to those knowledgeable in the sciences, “especially those regarding public administration.”23 That Münif seemed to see little difference between the science of administration and the natural sciences led some historians to suggest that the demonstrations were simply meant to elevate the status of science at large among the general public. For instance, Alper Yalçınkaya has argued that unlike familiar notions of nineteenth-century objectivity, where the credibility of scientific demonstrations rested on the nonintervention of a performer whose presence merely allowed predictable natural regularities to run their course, at Darülfünûn the role of the performers was far from neutral. To the contrary, the authority of the statesmen was crucial to elevating that of the knowledge they demonstrated.24 This ambition was cut short, the story goes, by the abrupt ending of this phase of the university life when the institution was moved and downsized shortly thereafter. A follow-up report attempted to make sense of this outcome, regretting that “lectures remained lectures only.”25

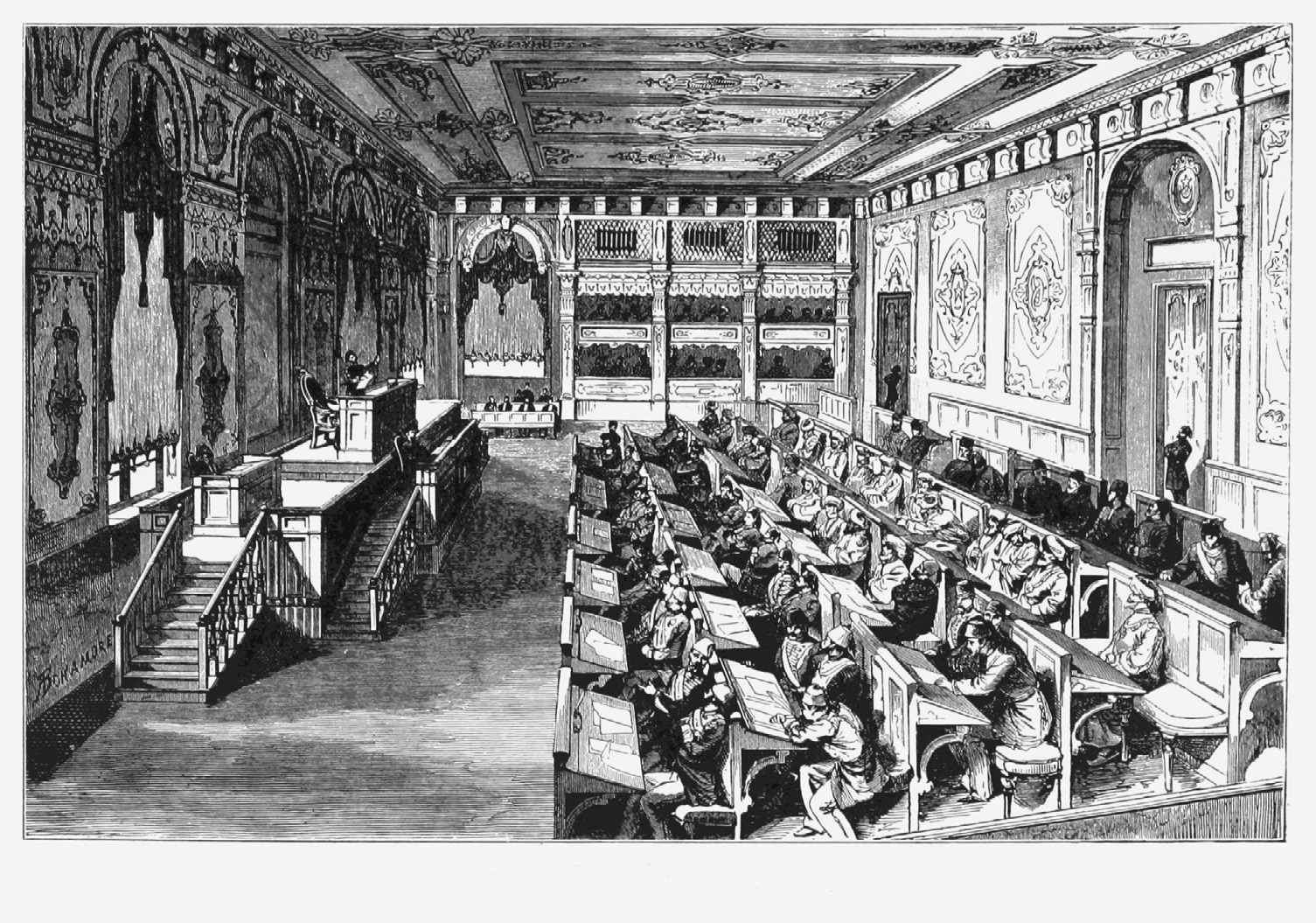

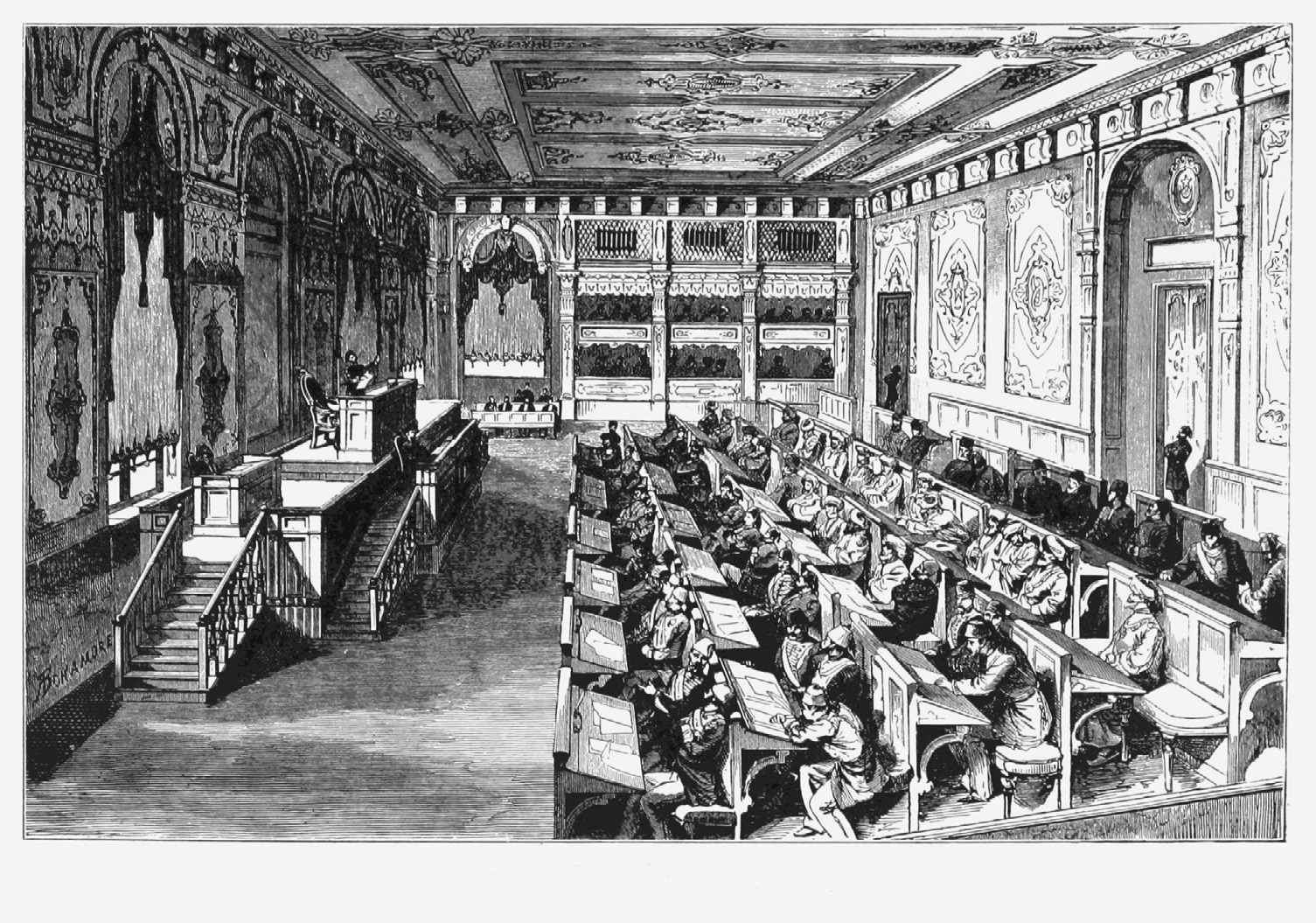

Yet following the story of the Darülfünûn building along a longer p. 23 historical arc reveals that the alliance between the universalism of the natural sciences and the Ottoman administration was more than just an exercise in mutual legitimation. After the university vacated the premises, Darülfünûn hosted miscellaneous ministries before getting transformed into the first Ottoman parliament. The same halls that had once housed expositions of the laws of gravity and the behavior of floating bodies in saline waters were now repurposed for discussing legislative laws which were to be universally valid empire-wide. The parliament and its attendant constitution were a culmination of the political vision of the Society of Young Ottomans, a loosely defined group of learned middle-ranking bureaucrats who advocated for a liberal political system by uncovering universal moral principles within the corpus of Islamic law (Sharia). Young Ottomans believed that political reforms should be grounded on something immutable, eternal, and universal and sought in the exegesis of Sharia and scripture.26 Figure 4 The Ottoman parliament, 1877. From William J.J. Spry, Life on the Bosphorus: doings in the city of the sultan. Turkey, past and present, 1895. The British Library, London.

The Ottoman parliament, 1877. From William J.J. Spry, Life on the Bosphorus: doings in the city of the sultan. Turkey, past and present, 1895. The British Library, London.

Darülfünûn was inaugurated as a parliament in March 1877, and legislators assembled for their first session in their retrofitted chamber six days after the intended opening day due to the delayed arrival of Parliament members deputized by distant provinces.27 In the weeks leading up to this second inauguration of the building, members elected in their provinces disembarked from passenger steamers and trains in Istanbul, many of whom were setting foot in the imperial capital for the first time. Upon their arrival, they presented themselves to the president of the Chamber and dealt with various formalities, the most important of which was their seat selection. They then visited the hall to mark their chosen seats with their visiting cards.28 The rows of seats were surrounded at both ends by two-tiered galleries, one of which was opulently furnished for the sultan, and five other galleries accommodated other spectators including government officials, journalists, and members of the general populace.29 p. 24 As the legislators finally seated themselves under the watchful eyes of an assortment of spectators, they began deliberating laws. One year earlier, the constitution had declared all subjects of the empire to be Ottoman, effectively proclaiming Muslim and non-Muslim subjects as equal before the law. In doing so, the parliament, tasked with making the new constitution operative, strove to enforce a new conception of justice. Up until then, the imperial mode of governing difference in the empire had rested on a conception of justice as the recognition and accommodation of particular circumstances. This kind of justice was embodied in the figure of the just ruler. The new imperial state, however, rested on a purported justice of administration, manifest in universal categories, rules, and procedures that were meant to transcend the individuals who enacted them. Thus for one short year, before the restoration of absolute monarchy in 1878, Darülfünûn was enlisted in the ongoing quest to depersonify justice.30

Once again, the architecture of Darülfünûn sat uneasily with the reforms it housed: If the building had proved too large for the university, its halls were deemed too small for the parliament, prompting bureaucrats to look for alternatives even before the parliament came to an abrupt end.31 It is true that the building did not seamlessly facilitate its program, but this does not discredit its role in reforms altogether. Here, architecture was delegated an anticipatory function, with each inauguration meant to herald reforms to come.

That these reforms did not materialize in the form of a monumental university or parliament in the late nineteenth century does not mean that the ideas latent in their visions bore no fruit. Shortly after the termination of the short-lived parliament, the universals of the natural sciences came together with the universals of administration in the emergent discourse of political economy, İlm-i Servet (science of wealth). To repeat, it was in his 1880 book on the subject that Ohannes characterized the task of political economy as one not of inventing but of discovering the natural laws that already governed economic and social life.32 Having taught the subject at the Imperial School of Administration (Mekteb-i Mülkiye) for twenty years (between 1877 and 1897), Ohannes’s lectures did not remain lectures only, as it were.33 They landed on the ears of many cohorts who went on to join the ranks of Ottoman officialdom and run the affairs of the empire, thus leaving a significant imprint on both political thought and practical matters of administration.34

Midway through his tenure at Mülkiye, Ohannes had a brief stint at the school of fine arts, where he delivered the first lectures on aesthetics in 1891. Little evidence survives around the circumstances of his hiring—aside from a passing expression of hope in his opening remarks p. 25 that he would rise up to the task of teaching such a delicate subject in which he had no expertise.35 Yet, that the science of wealth and the science of aesthetics converged in Ohannes’s teaching at that particular moment was not a coincidence nor simply a mark of an exceptional career. Ohannes’s writings on aesthetics and political economy grappled with a problem that occupied many of his contemporaneous reformers, namely, the status of universals in a world characterized by cultural differences.

While political economy emerged as a technology of governance for the new administrative state, aesthetics became a privileged domain in which the new governmental reason sought to reconcile universals and particulars. If the imperial mode of governing difference had achieved social cohesion by granting nonterritorial autonomy to geographically dispersed groups, the new form of polity, which conceived of sovereignty in territorial terms and sought to govern an abstract collective of nominally equal citizens, had to achieve the cohesion necessary to reproduce itself by other means. Imperial citizenship was too weak of a binding force, and some subjects rejected it outright or saw it as detrimental to their ways of life.36 The Ottoman elite’s preoccupation with aesthetics, which found expression in the school of fine arts where Ohannes lectured and its nearby museum, was one response to this dilemma.37 However, reading Ohannes’s writings on aesthetics and political economy alongside each other reveals that the shift in governance in the empire at the time was not one of turning cultural difference into sameness. Rather, it was toward inventing frameworks within which difference could exist on new terms.

Compilation

Ohannes addressed the relationship between universals and particulars in aesthetics most explicitly in a lecture he titled “Idealism and Realism.”38 Following a brief introduction of each pole of the duality—the exemplary metaphysical ideal on one side and the slavish imitation of nature on the other—he proposed a synthesis that could be achieved by combining “the powers of dissection, generalization, and making whole [bütünleș tirme]” of the human mind with artistic sense. In this way, rather than striving to imitate a metaphysical ideal or to mindlessly copy nature, the artist gained “the power of creation” by “organizing and correcting the things scattered in nature, which [were] often not free from defects or unsuitable as artistic subjects” giving them “a sense of conformity, and render[ed] nature more harmonious and perfect.” In so doing, Ohannes continued, “the artist invent[ed] a genus [cins] by bringing together [bir araya getirerek] the forms that characterize[d] all the species [türler] of that genus in nature.”39 In other words, in his telling, p. 26 invention came about through a process of compilation.

When does compilation amount to something more than the sum total of its parts? This question permeated the reformist efforts of the Ottoman administration not only in aesthetics but also in law. Take, for instance, the jurist Ahmed Cevdet Pasha (1822–1895), who drafted the civil code (Mecelle-i Ahkâm-ı Adliye) of the empire, and insisted that the task of the drafters was one of compiling existing regulations and not of creating new ones.40 Produced between 1869 and 1876, the Mecelle covered matters of private law such as debt, ownership, and contracts. As the need for more uniform rules to govern exchange became more acute with expanding markets in the mid-century, Ottoman bureaucrats were divided between adopting the French civil code and codifying Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh). The latter camp gained the upper hand, and a committee of drafters headed by Cevdet Pasha turned the corpus of Islamic jurisprudence into systematically classified and numbered clauses, arranged in sixteen books.41

Many authors weighed in on whether the Mecelle was compilation or code. Max Weber, for one, did not consider it to be a code “in the true sense, but simply a compilation of Henefite norms.”42 Since then, others have argued that it was, in fact, a code. As opposed to the kanunnâmes, which were law books covering matters of land tenure and taxation the Ottoman government distributed to the provinces in the early modern period—that is, laws that were not intended for uniform application across the empire—the Mecelle was systematic and its scope was universal.43 Some have speculated that Cevdet Pasha avoided calling the Mecelle a code to circumvent charges of innovation (in a derogatory sense) on Islamic jurisprudence.44 Others have noted that the Mecelle allowed much room for rule by exception by including principles such as “necessity makes permissible what is forbidden,” and “rulings change with the change of time,” departing from contemporaneous projects of reform that searched for universal principles that would apply to all circumstances at all times.45 When read alongside Ohannes’s notion that compilation amounts to invention, however, the Mecelle’s status as compilation appears not to be antithetical to its status as code.

Similarly, in maintaining that the science of wealth as a technology of governance did not invent but only discovered and proved natural laws that governed the opulence of human society, Ohannes suggested that the task of political economy was to discern the inner structure of the concrete. It meant looking beyond the apparent arbitrariness of experience for regularities in economic and social life. In this sense, it was not that different from the task Ohannes assigned to aesthetics, whereby the artist “invents a genus” by “bringing together the forms that characterize all the species of that genus in nature.”46 In suggesting p. 27 that invention came about through a process of compilation, Ohannes, like the jurists before him, conveyed a new attitude toward novelty. Figure 5 Interior view of the Imperial Library at the Yıldız Palace. Abdülhamid II Photography Collection, Rare Works Library, Istanbul University.

Interior view of the Imperial Library at the Yıldız Palace. Abdülhamid II Photography Collection, Rare Works Library, Istanbul University.

The novelty of this attitude stands in sharper relief when compared to the discourse around earlier reforms. At the turn of the nineteenth century, almost every reform in the empire was preceded by the word “new.” The most significant of these reforms was the New Order, or Nizam-i Cedid, a term that initially denoted the reform’s central innovation, the new army, but eventually came to encompass the entire reform movement under Sultan Selim III (r. 1789–1807). As its name suggests, the New Order celebrated novelty in its ambition to overhaul existing administrative, military, and fiscal structures, despite its underlying ambivalence towards the actual novelty of the new.47 Though by no means monolithic, the appeal of novelty in government was itself a culmination of a longer process whereby terms such as “new” (cedid), “renewal” (tecdid), “innovation” (icad), and “invention” (ihtira’) became much more prominent not only in political discourse but also in literary, architectural, and urban texts.[fn 48 By the time Ohannes penned his writings in the final decades of the century, the mood had clearly shifted. In the interim, successive peasant revolts in the provinces served as cautionary tales for heavy-handed change. This cautious approach toward novelty influenced the universalist ethos of the reforming state. Ohannes’s appeal to compilation as a means for invention can thus be read as part of a broader shift away from overt proclamations of novelty in a climate where the “new” had lost at least part of its former appeal.

To be sure, this interest in compilation in and of itself was not unique to the Ottoman Empire. It is well known that the nineteenth century saw an exponential spread of compilatory technologies such as atlases, encyclopedias, dictionaries, and museums globally, and the Ottoman p. 28 case was no exception in this regard.49 Historians have argued that the spread of these technologies was primarily linked to a territorial logic of expansion characteristic of contemporaneous European empires.50 What was unique in the Ottoman case was that the interest in compilation emerged at a moment when the prospects of territorial expansion had been largely foreclosed, giving rise to new ways of conceptualizing land, subjects, and territory.

Take the definition of land Ohannes gives in his Mebâdi-i Ilm-i Servet:

According to the science of wealth, the word “land” (arz) refers not only to cultivable soil. This term denotes all natural resources [vesait-i tabiiyye] that are connected to the land, i.e., mines, quarries, forests and pastures, flowing waters, and lakes, in other words, all the places where various industries are carried out.51

Expanding the category of what constituted land, however, came with a crucial caveat.

[O]ne of the most important features of land is that it is limited [mahdûd]. Both the amount of land suitable for agriculture and the amount of mines and forests. As a result of this limitation, it is possible to own the land individually [s¸ahsen ve münferiden temellük], which … is an essential basis of civilization.52

European empires confronted this limitation through territorial conquest. Yet, by the time Ohannes composed these words, recent losses of territory in the Balkans were looming large over Ottoman legislators, and stabilizing the empire’s sovereignty over its remaining territories gained paramount urgency. One productive if not obvious site of this new territorial logic was the Imperial Museum, whose new building was inaugurated in 1891—the same year in which Ohannes delivered his lectures on aesthetics at its neighboring school of fine arts. It might therefore be worthwhile to ask: What kind of a compilatory technology is an archeology museum decoupled from an expansionist territorial logic?

Unlike its European counterparts, the mission of the Imperial Museum in Istanbul resided not in compiling trophies of recent conquests, but in stabilizing a fragile sovereignty. Historian Wendy Shaw has convincingly elaborated the role of the Imperial Museum as “an expression of territoriality.” Yet Shaw has argued that, in housing solely archaeological artifacts—to the exclusion of artworks—the museum was “divested from aesthetics but wed to territory.” In that sense, “patrimony belonged not in the realm of art-historical discourse, which relied on words alone, but the material language of the territory.”53 By situating the territorial strategies of the museum within a mutual preoccupation with universals p. 29 in aesthetics and government, I posit a much stronger affinity between art-historical words, so to speak, and the materiality of territory.

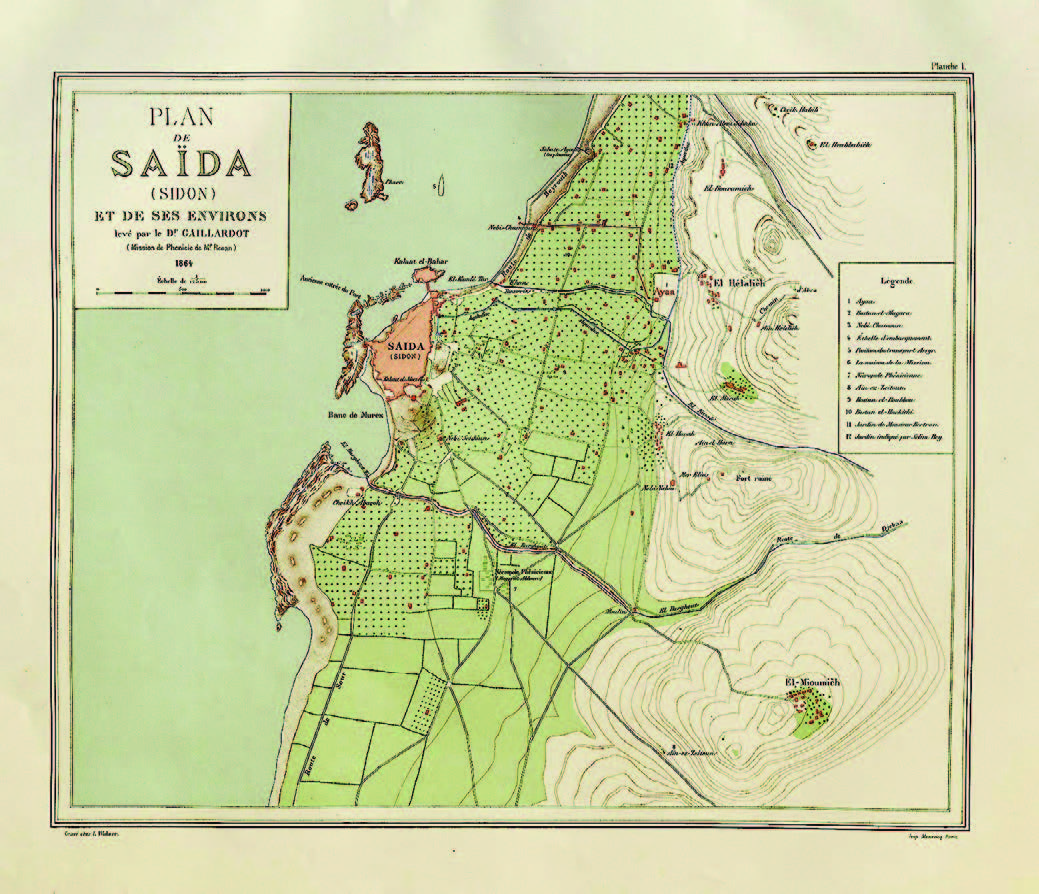

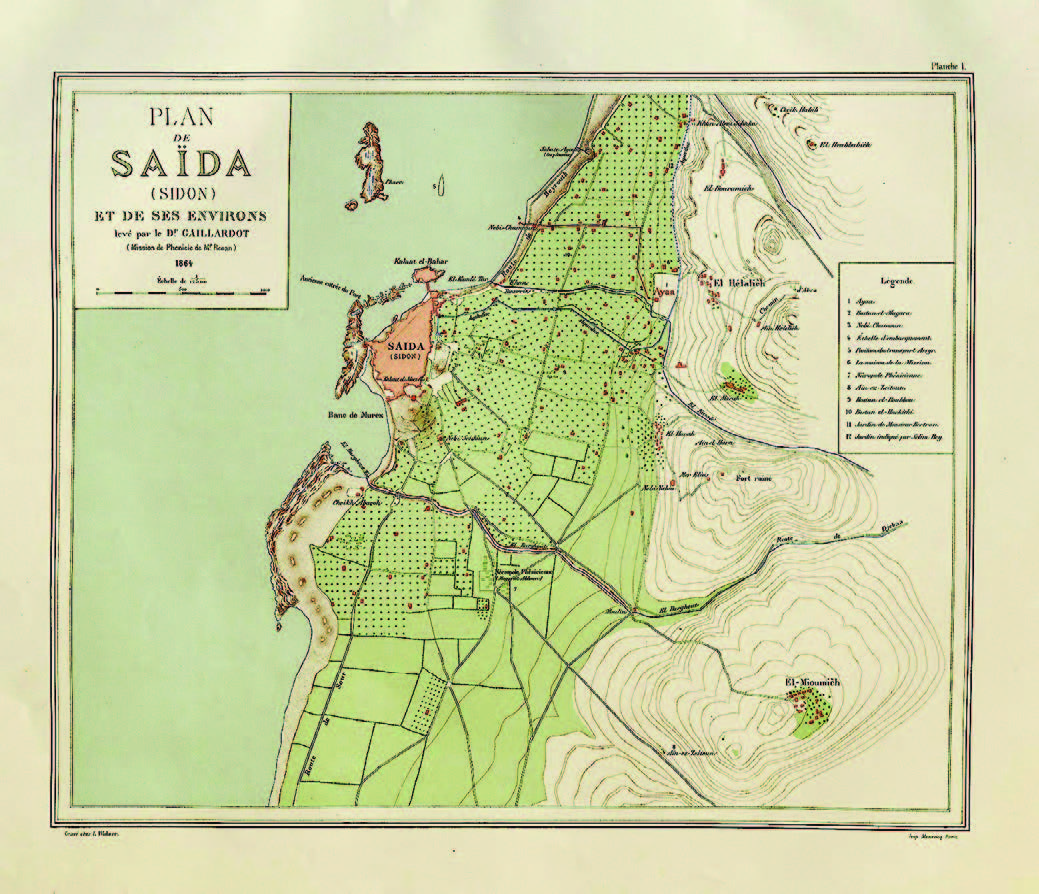

Figure 6 Dr. Gaillardot, Plan de Saïda (Sidon) et de ses environs (Map of Saïda and its surroundings), 1864. From Osman Hamdi Bey and Theodore Reinach, Une Nécropole Royale à Sidon Fouilles de Hamdy Bey, Istanbul, 1887. Figure 7

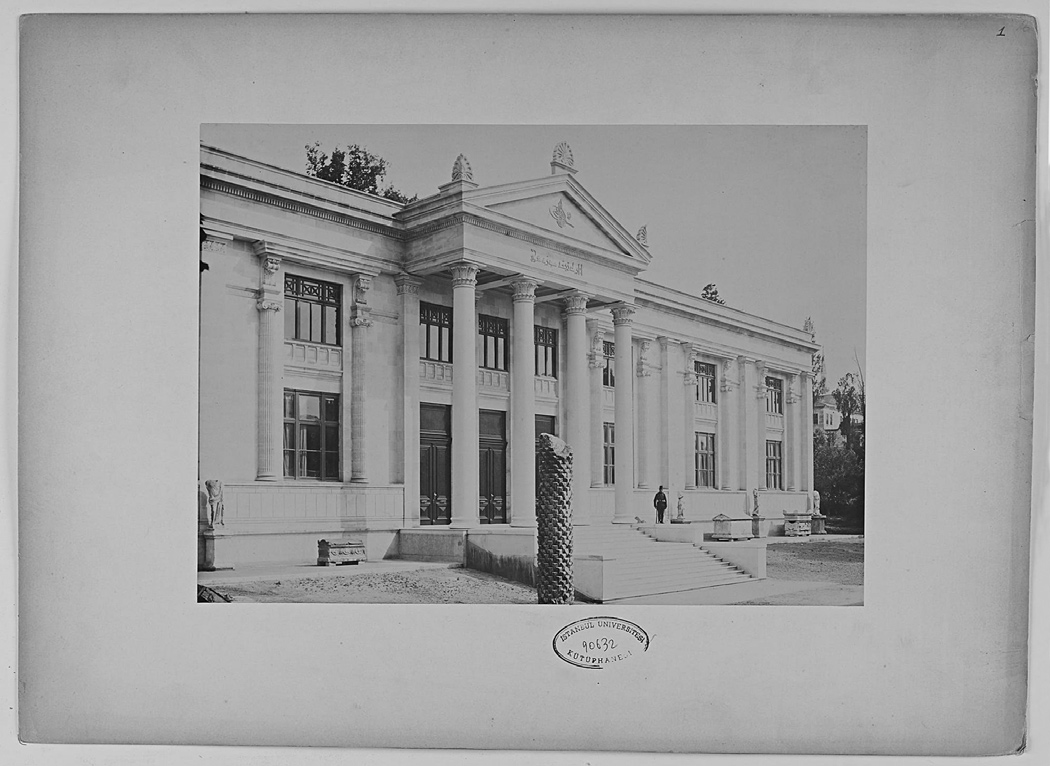

Dr. Gaillardot, Plan de Saïda (Sidon) et de ses environs (Map of Saïda and its surroundings), 1864. From Osman Hamdi Bey and Theodore Reinach, Une Nécropole Royale à Sidon Fouilles de Hamdy Bey, Istanbul, 1887. Figure 7 The new annex of the Imperial Museum, inaugurated in 1891. Abdülhamid II Photography Collection, Rare Works Library, Istanbul University.

The new annex of the Imperial Museum, inaugurated in 1891. Abdülhamid II Photography Collection, Rare Works Library, Istanbul University.

In the late nineteenth century, artifacts dug up from across the empire were transported to the Imperial Museum. Many made stops for temporary display in the courtyards of government palaces or in high schools in the provinces where they were uncovered, thus circulating within the thickening architectural network of the consolidat- ing bureaucracy.54 Once the objects reached the museum, they were often labeled in early catalogues using the location of their discovery and the name of the administrator who had sent them to the museum, signaling that the contemporary relationship the objects had to Ottoman bureaucracy and territory mattered as much as their status as carriers of historical meaning.55 This territorial logic appears clearly in the display of the museum’s main collection; a group of twenty-six sarcophagi unearthed in Saida in what was then the province of Damascus (present-day Lebanon). A quarry owner had happened upon the ancient necropolis in 1887 upon noticing a tomb shaft, which led to the discovery of seven rock-cut burial chambers. The news soon reached the museum director, Osman Hamdi, who supervised the excavation and saw to it that a new building was constructed to house its yield.56

The design of this new annex of the Imperial Museum deployed the universalist idiom of neoclassicism in favor of an Ottoman claim to Hellenistic antiquities. After all, in the words of a contemporaneous French historian, the Ottoman empire possessed “more than half of the ancient Greek world,” whether buried in its soil or increasingly exhibited in its capital.57 Levantine architect Alexandre Vallaury (1850–1921) modeled the building after two of the objects dug up in Saida; the Alexander Sarcophagus and that of the Wailing Women.58 The architecture thus grounded neoclassical aesthetics—which connoted the universalist ideals of European civilizational missions at the time—in the particularities p. 30 larities of artifacts unearthed in Ottoman land.

These particularities extended further to strategies of display. The collections of the Imperial Museum were not organized according to a chronological scheme as was the norm in European museums. Instead, objects were organized geographically according to the site of their manufacture. Sarcophagi made in Egypt and later in Phoenicia were grouped together, as were those manufactured in Attica (in present-day Greece).59 If we were to follow Ohannes’s compilatory logic, whereby a genus is invented by compiling its constituent forms, the genus of the collections and legislative practices of the Imperial Museum was Ottoman territory.

In that sense, the realm of aesthetics not only allowed for reconciling universals with particulars, it also had a privileged power to do so. In his aesthetics lectures Ohannes maintained that

many people exist in the realm of reality, each one is present with his own name and personality. There is no human in the abstract. Creating a person without a name in the world [ismi olmayan bir insan], or a lion with no likeness in another [aynı bulunmayan bir aslan], is a power peculiar to art.60

At first glance, Ohannes’s invocation of the lion as an example might seem odd. Yet a variety of lion sculptures were on display at the museum, including within the centerpiece object, the Alexander Sarcophagus, which Ohannes would have likely encountered.

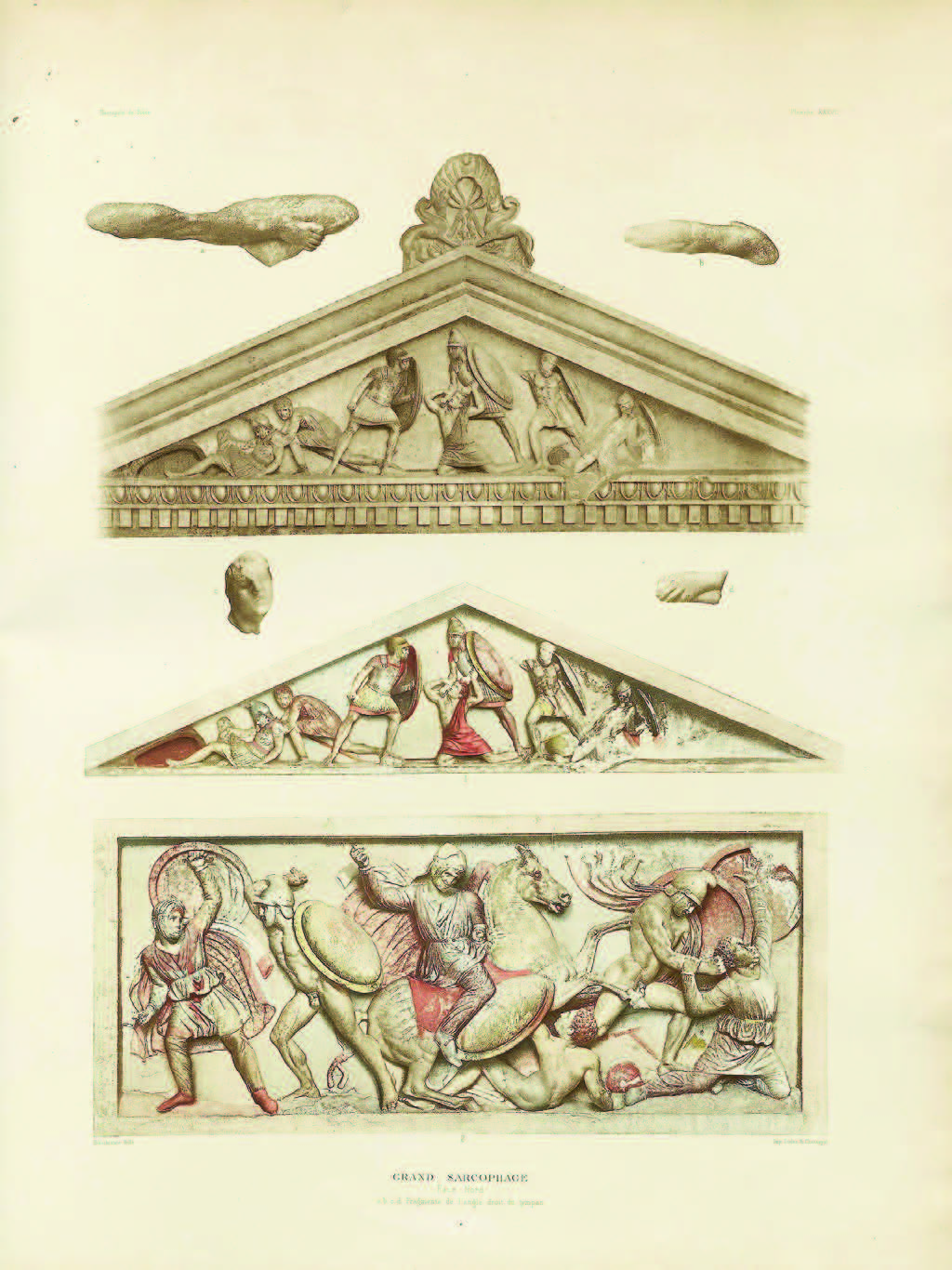

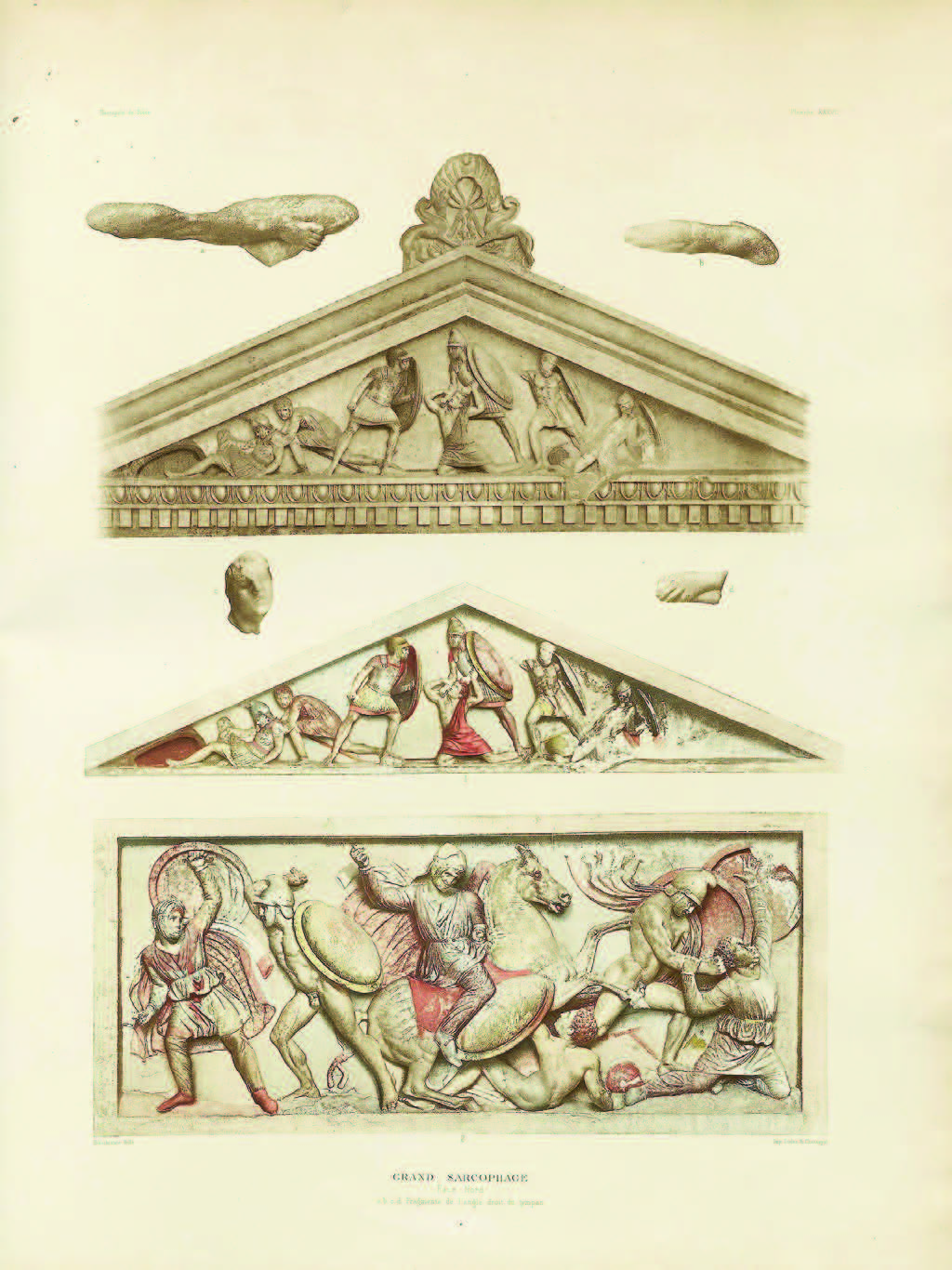

Figure 8 Sarcophage des Pleureuses (Sarcophagus of the Wailing Women). From Osman Hamdi Bey and Theodore Reinach, Une Nécropole Royale à Sidon Fouilles de Hamdy Bey, Istanbul, 1887. Figure 9

Sarcophage des Pleureuses (Sarcophagus of the Wailing Women). From Osman Hamdi Bey and Theodore Reinach, Une Nécropole Royale à Sidon Fouilles de Hamdy Bey, Istanbul, 1887. Figure 9 Grand Sarcophage (Grand Sarcophagus, later named Alexander Sarcophagus). From Osman Hamdi Bey and Theodore Reinach, Une Nécropole Royale à Sidon Fouilles de Hamdy Bey, Istanbul, 1887.

The sarcophagus is adorned with four guardian lions, one on each corner of its two pediments. One side depicts Alexander the Great hunting an Asiatic lion, a species that roamed the lands between eastern Anatolia and central India.61 The particularity of this lion pointed to a geography that existed outside of typically Hellenistic motifs. As a “lion with no likeness in another,” to borrow Ohannes’s formulation, motifs of the Asiatic lion in Hellenistic artifacts would have supported the Ottoman government’s patrimony of Greek antiquity that set it apart from (if not above) European Hellenophilia. The unique lion and the nameless person invoked by Ohannes were arguably products of the same governmental reason. The unique lion shifted Greek antiquities’ conventional field of reference. According to Ohannes, then, if art had a unique power to create, how did its other creation, the “nameless p. 31person,” matter?

Grand Sarcophage (Grand Sarcophagus, later named Alexander Sarcophagus). From Osman Hamdi Bey and Theodore Reinach, Une Nécropole Royale à Sidon Fouilles de Hamdy Bey, Istanbul, 1887.

The sarcophagus is adorned with four guardian lions, one on each corner of its two pediments. One side depicts Alexander the Great hunting an Asiatic lion, a species that roamed the lands between eastern Anatolia and central India.61 The particularity of this lion pointed to a geography that existed outside of typically Hellenistic motifs. As a “lion with no likeness in another,” to borrow Ohannes’s formulation, motifs of the Asiatic lion in Hellenistic artifacts would have supported the Ottoman government’s patrimony of Greek antiquity that set it apart from (if not above) European Hellenophilia. The unique lion and the nameless person invoked by Ohannes were arguably products of the same governmental reason. The unique lion shifted Greek antiquities’ conventional field of reference. According to Ohannes, then, if art had a unique power to create, how did its other creation, the “nameless p. 31person,” matter?

Individuation

If compilation was one concept that mediated the tension between universals and particulars in aesthetics and political economy in the empire, individuation was another important technique. In his writing on political economy, Ohannes takes the individuation of the self as an a priori for an argument about private property:

In philosophical terms, just as self and non-self (i.e., me and someone other than me) are separate from each other, it is also necessary to separate the things that belong to me from those belonging to someone else (bana ve gayrıhu aid olan s¸eylerin de tefrikini icab eder).62

The individual here, not unlike the nominally equal Ottoman citizens birthed by the nationality law of the 1860s or the Mecelle, for that matter, is imagined to be autonomous and free to own, transact, and enter into contracts. Similarly, the individuals presupposed by Ohannes’s characterization of society as a “composite body” needed to be equal and equivalent to each other to enter into relations of exchange, which were their primary mode of interdependence.

It did not escape Ohannes, however, that such an individual was a mere ideal. Thus, in asserting that bringing a nameless person into being was the privileged domain of art, Ohannes suggested that that individual did not simply exist but had to be created. What was the relationship, then, between the individual presupposed by political economy and that as brought into being by aesthetics in Ohannes’s writing? Here lied the crux of how the concept of the individual reconciled the abstraction of the universal with the particularity of the concrete.

It is widely accepted that an abstract conception of individuality has long—at least since John Locke—formed the bedrock of liberal arguments. Critical histories of liberal thought have argued that the abstraction of liberal individuality obscured the density of social relations and forms of life that constituted its real conditions of possibility. They maintained that colonial legislators, in their quest to actualize liberal abstractions in distant locales, confronted dense social relations and forms of life that prompted them to come to terms with the limits of their allegedly universal ideals.63 Andrew Sartori has recently complicated such p. 32 a straightforward antagonism between the abstractions of liberal thought and the concreteness of reality, suggesting that the relationship between the two was, in fact, bidirectional.64

Figure 10 Polychromy on the Grand Sarcophagus (later named Alexander Sarcophagus). From Osman Hamdi Bey and Theodore Reinach, Une Nécropole Royale à Sidon Fouilles de Hamdy Bey, Istanbul, 1887.

Aesthetics was a privileged realm where this bidirectional relationship played out. Recall the terracotta heads at the Imperial Museum that this essay started with. As discussed earlier, the display encompassed sculpted heads of vastly different styles produced by ancient peoples interpellated by the law of antiquities as former Ottoman residents. Yet, because the idea of the Ottoman subject was not an abstraction that hinged on a thinning of the empirical, the particularities of these artifacts were not dissolved into the totalizing category of the (ancient) Ottoman. Rather, Ottoman citizenship was a real abstraction that served the purpose of creating equivalent social entities capable of engaging in capitalist relations of exchange despite their differences. In this regard, the free and equal individuals that Ohannes took to be a precondition to private property were necessarily atomized and antagonistic. Aesthetics, in this thinking, served as a binding force necessary to achieve social cohesion as social relations became more commercialized.

Polychromy on the Grand Sarcophagus (later named Alexander Sarcophagus). From Osman Hamdi Bey and Theodore Reinach, Une Nécropole Royale à Sidon Fouilles de Hamdy Bey, Istanbul, 1887.

Aesthetics was a privileged realm where this bidirectional relationship played out. Recall the terracotta heads at the Imperial Museum that this essay started with. As discussed earlier, the display encompassed sculpted heads of vastly different styles produced by ancient peoples interpellated by the law of antiquities as former Ottoman residents. Yet, because the idea of the Ottoman subject was not an abstraction that hinged on a thinning of the empirical, the particularities of these artifacts were not dissolved into the totalizing category of the (ancient) Ottoman. Rather, Ottoman citizenship was a real abstraction that served the purpose of creating equivalent social entities capable of engaging in capitalist relations of exchange despite their differences. In this regard, the free and equal individuals that Ohannes took to be a precondition to private property were necessarily atomized and antagonistic. Aesthetics, in this thinking, served as a binding force necessary to achieve social cohesion as social relations became more commercialized.

The emergence of aesthetics as a discourse in the late-nineteenth-century Ottoman Empire, then, can be viewed as a state effect, a concept defined by Timothy Mitchell as “techniques that enable mundane material practices to take on the appearance of an abstract, nonmaterial form,” namely, that of the state.65 Historians of the empire have long critiqued state-centered approaches toward the study of Ottoman history. In particular, some have taken issue with dominant readings of law as a manifestation of an omnipresent sovereign will, assumed to have always gotten its way. Such critiques have suggested that historians would be better served by turning their attention to how things played out on the ground in search of a more faithful picture of the actual workings of governance.66 The episodes I highlighted point in a different direction. They show that universals, whether in the form of sovereignty, law, or the imperial citizen, were not simply abstract mischaracterizations of concrete reality. Rather, they were abstractions that actively shaped the concrete. In that sense, examining the workings of p. 33 universalist thinking beyond the so-called West can allow for a critique of Eurocentrism that goes further than showing how concepts got altered and appropriated as they traveled. Instead, it presents an opportunity to reconsider what universals are and how they have always functioned.

It is telling that the sarcophagi collection attracted international scholarly attention at the time due to the fact that the artifacts had retained traces of their original colors exceptionally well. They thus supported—albeit retrospectively—arguments on the use of polychromy in Greek antiquity, a controversial topic in the nineteenth century. In weighing in on these international debates, the Ottoman Empire was not just a test case for whether Western universals managed to hold outside their European settings. Rather, it transformed the understanding of what universals had been all along.

I wish to thank Zeynep Çelik Alexander and Lucia Allais, to whom this article owes its existence, for their generous insights throughout the writing process. I am also grateful to fellow participants in the State Effects conference at the Buell Center, where I presented a version of this research: Cole Roskam, Daniel M. Abramson, Sophie Cras, Rosalind C. Morris, Sheila Crane, Sonali Dhanpal, Brodwyn Fischer, Brian Larkin, and Bruno Carvalho for insightful feedback on the paper. For thoughtful comments on early drafts, I am indebted to Camille Cole, Chelsea Spencer, Phoebe Springstubb, Roxanne Goldberg, Erin Freedman, Lucia Galaretto, and Matthew Lopez. Ultan Byrne has been a crucial interlocutor in shaping my ideas about the state for this research and beyond, and Deren Ertas¸ looked over my early translations of Ohannes’s aesthetics lectures and has enriched my understanding of Ottoman political economy. A word of thanks is likewise due to the editorial team of Grey Room, especially to Alex Zivkovic for smoothly steering the editorial process. Unless otherwise specified, all English translations of original sources that appear in the text are mine.