Figure 1 Installation view of Olmec:

Colossal Masterworks from

Ancient Mexico, Los Angeles

County Museum of Art,

October 2, 2010–January 9, 2011.

Digital image © 2012 Museum

Associates/LACMA. Licensed

by Art Resource, NY.

Installation view of Olmec:

Colossal Masterworks from

Ancient Mexico, Los Angeles

County Museum of Art,

October 2, 2010–January 9, 2011.

Digital image © 2012 Museum

Associates/LACMA. Licensed

by Art Resource, NY.

p. 12

In October 2010, a display of Olmec art served as the inaugural exhibition for Renzo Piano’s Resnick Pavilion, the brand-new addition to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA).1 Two colossal heads, naturalistic portraits carved out of single monoliths of basaltic rock sometime between 1500 and 400 BCE in what is today Veracruz, Mexico, stood out as the primary artifacts in the show. Michael Heizer, the son of Olmec archaeologist Robert Heizer, designed a set of stands for these objects made of Cor-Ten steel, steel that weathers over time to take on an even patina of rust and a material used widely in art and architecture in the last half century.2 Formally, the stands resemble positive representations of the much larger trenches and dugout formations that define Heizer’s more canonical work. They are also reminiscent of the kinds of excavation trenches that archaeologists like Heizer’s father have used to study the Olmecs. While the dialogue between artistic and anthropological objects was central to the installation, the juxtaposition of ancient objects against Heizer’s modernist stands and the slick surfaces of Piano’s building was no less important to the display’s intended meanings.

LACMA’s recent show calls to mind an “old” LACMA exhibition. San Lorenzo Monument Five, a colossal head from the site of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan in Veracruz, was one of two heads featured in LACMA’s recent exhibition. LACMA exhibited the same head more than five decades ago. From September 1963 to January 1964, this ancient portrait of an Olmec ruler greeted visitors to LACMA’s building, located at what was then Exposition Park in Los Angeles. The head rested on a heavy pedestal much less formally intricate than the ones Heizer designed in 2010. The earlier pedestal was not made of Cor-Ten steel, and it was placed over the steps leading to the museum entrance.

The catalogue for LACMA’s recent show elides the powerful resemblance between these two episodes. More important, it sidesteps fundamental questions concerning why Olmec heads retain their appeal for elaborate museum exhibitions and why the circumstances of their display have remained so highly consistent over time.3 Instead, catalogue editors Virginia Fields and Kathleen Berrin discuss how, beginning in 1939, expeditions by Matthew Stirling, an archaeologist sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution and National Geographic Society, gave mainstream exposure to Olmec art, which Mexican explorers had discovered p. 13 in the 1860s.4 They also discuss how Olmec colossal heads in particular spurred specialized art-historical and archaeological debates in the decades after Stirling’s discoveries, mostly owing to their puzzlingly ancient date compared to artifacts from the Aztec and Mayan traditions, which were at that time better known in the United States.5

By not discussing the resemblance between LACMA’s own displays of Olmec heads in 1963 and 2010, these scholars neglect the complex history of museological and artistic appropriations of this archaeological tradition, a history that has yet to receive serious attention. This essay addresses one aspect of this context: Olmec art’s overlooked relationship to two emerging trends in early-to-mid-1960s art and its interrelation to the period’s exhibitionary culture. The first is the production of “public” sculpture, a set of loosely affiliated efforts to rethink the relationship between architecture and sculpture that is often of large scale and situated in urban spaces. The second is land art, an equally fluid set of practices that questions the dialogue between artistic production and environmental and territorial concerns. At a key turning point in the recent history of “American” art, a set of transposed Olmec heads served as a material, symbolic, and temporal fulcrum for a series of seemingly unrelated artistic and curatorial explorations. Exhibitions of Olmec heads facilitated the simultaneous consumption of these objects as deterritorialized, mass-mediated images and as imposing, singular objects. These parallel modalities of consumption had a profound impact on how these Mesoamerican artifacts became central to artistic and critical debates of the period.

LACMA’s 1963 show Masterworks of Mexican Art: From Pre- Columbian Times to the Present was one of several highly visible Figure 2 San Lorenzo Monument Five in

the exhibition Masterworks of

Mexican Art: From Pre-Columbian

Times to the Present, Los Angeles

County Museum of Art, 1963.

Robert F. Heizer Papers, National

Anthropological Archives,

Smithsonian Institution. p. 14 displays of Olmec colossal heads in the United States during the early 1960s. Additional exhibitions included The Olmec Tradition, organized by James Johnson Sweeney at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in 1963, as well as the display of two heads, one of them San Lorenzo Monument Five, the same head shown at LACMA in the early 1960s and in 2010, at the Mexican pavilion for the New York World’s Fair of 1964-1965, held in Flushing Meadows, Queens. At all of these shows, the diplomatic stakes were as high as the curatorial ones.

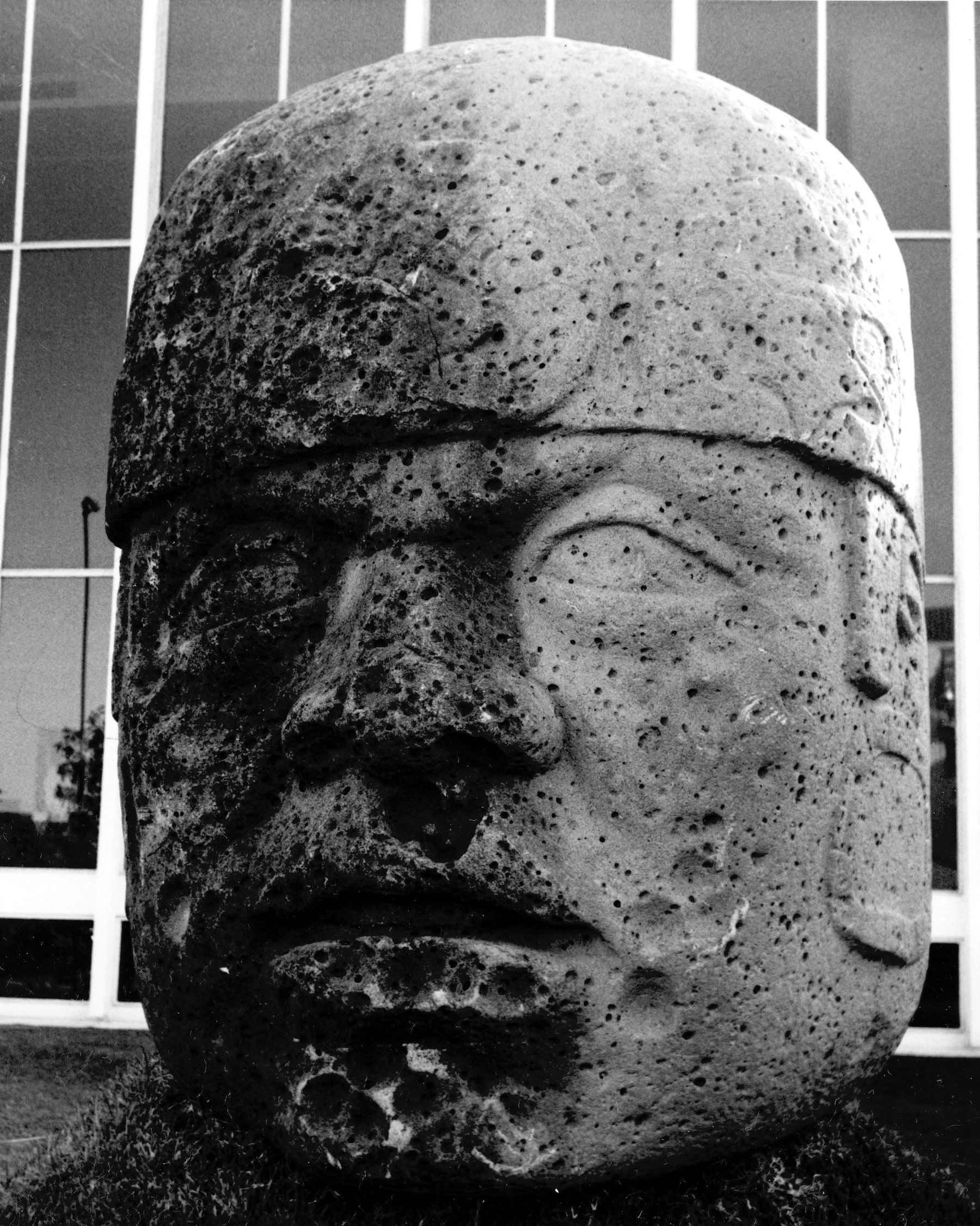

San Lorenzo Monument Five in

the exhibition Masterworks of

Mexican Art: From Pre-Columbian

Times to the Present, Los Angeles

County Museum of Art, 1963.

Robert F. Heizer Papers, National

Anthropological Archives,

Smithsonian Institution. p. 14 displays of Olmec colossal heads in the United States during the early 1960s. Additional exhibitions included The Olmec Tradition, organized by James Johnson Sweeney at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in 1963, as well as the display of two heads, one of them San Lorenzo Monument Five, the same head shown at LACMA in the early 1960s and in 2010, at the Mexican pavilion for the New York World’s Fair of 1964-1965, held in Flushing Meadows, Queens. At all of these shows, the diplomatic stakes were as high as the curatorial ones.

LACMA’s 1963 show, for example, was one of the most ambitious encyclopedic shows ever organized by the Mexican state during a period of heightened official efforts to showcase Mexican art and culture domestically and internationally. Spanning several centuries of artistic production, this show positioned Olmec art as the point of origin of all subsequent artistic traditions in Mexico, including those of the twentieth century. Fernando Gamboa, who curated several other encyclopedic shows of Mexican art for foreign audiences, organized this large-scale undertaking. Commissioned by state-sponsored cultural institutions from Mexico, the massive exhibition of thousands of original artifacts traveled across European capitals and the United States for four full years: 1960-1963.6 New York Times writer Murray Schumach estimated that about nine million people saw the exhibition before it arrived in Los Angeles, its final stop, and in the first two weeks at LACMA it drew over 34,000 visitors.7

Just as significant as the diplomatic implications of the Masterworks show at LACMA, The Olmec Tradition in Houston, and the displays of two Olmec heads in New York was the expensive and technologically complex transportation of heavy monoliths that these exhibitions entailed.8In each of these three exhibitions, curators installed colossal heads in modernist architectural environments, and the clashes between modern and ancient surfaces and materials that these curatorial interventions spurred were central to their visibility and influence. The exhibitions thus exemplify the kinds of discursive operations that Walter Benjamin describes as “doublings” of time. Central to the production of modern historical knowledge, Benjamin argues, is the deliberate staging of confrontations between fragments of ancient history and bits of modern life in order to emphasize the technological and political wherewithal necessary to traverse the distance between these two domains. In the nineteenth-century contexts that Benjamin surveys, these spectacles had remarkably malleable propaganda applications, a condition they retained in the 1960s.9

As Pamela Lee shows, central to the practices of U.S. artists and critics in the 1960s was an interest in concepts of time that challenged then-dominant notions of teleological temporal advance, p. 15 especially those derived from Mesoamerican art historian George Kubler’s influential book, The Shape of Time (1962). Artists such as Heizer and Robert Smithson were especially drawn to alternative approaches to historical time that emphasized cyclical analogies between ancient and modern artifacts. The doublings of time that defined the “discovery” of Olmec art during the early 1960s reinforced these notions.10 What follows is an attempt to make sense of the encounter between Mesoamerica’s oldest artistic tradition and this evolving set of artistic, curatorial, and critical concerns, including its lasting echoes in our immediate past.

| | | | |

The “discovery” of the Olmec colossal heads fueled the imagination of U.S. audiences from the beginning. Stirling had worked on excavations in indigenous territories on the U.S. and Canadian West Coasts, as well as in Dutch New Guinea and Ecuador, before turning to Mexico, and he was no stranger to the fascination “exotic” artifacts could elicit when showcased in museums, as well as through the mass media. He published the first account of his expeditions in Veracruz and Tabasco, which yielded the discovery of five colossal Olmec heads, in National Geographic in 1940.11 Although Stirling discusses his discovery, excavation, and documentation of a wide range of stone sculptures from the Veracruz sites of Tres Zapotes and Cerro de las Mesas, as well as the site of La Venta in the state of Tabasco, he describes the Olmec heads as his most significant finds. In his words, stumbling upon the last three heads represented “the climax of our most interesting period of Mexican excavation.”12

Stirling also points out the diversity of facial expressions, sizes, and individualized anthropomorphic depictions that the heads evince, and he marvels at their differences from most other Mesoamerican artifacts known at the time. Introducing a question of enduring fascination for every subsequent researcher of Olmec culture, Stirling expresses his interest in how the ancient inhabitants of these ceremonial centers moved the heads:

Most of these stones are large and heavy. We were assured by petroleum geologists in the region that no igneous rock of the type from which these monuments were carved exists at any point closer to the site than 50 miles. How were these immense blocks of stone moved this long distance down rivers and across great stretches of swamp to the location where they now rest? Certain it is that the people who accomplished this feat were engineers as well as artists.13

Stirling’s puzzled statement makes clear the Olmecs’ aura of obscurity in both popular literature and specialized archaeologi-p. 16 cal research. However, for mass audiences in the United States, Mesoamerican art was not entirely unfamiliar by 1940. As Holly Barnet-Sánchez shows, interest in pre-Columbian art from Mexico was prominent in the U.S. popular imagination of the 1930s and 1940s. At this time, exhibitions, publications, and popular literature motivated by Pan-Americanist agendas on both sides of the border glorified the avowedly common pre- Columbian heritages of Mexico and the United States. In the United States, the attempt to create the sense of a shared cultural heritage across the border through the display of pre-Columbian art became increasingly significant during the Second World War, as the need to secure cultural and economic relations between the United States and Mexico became a paramount strategic goal.

Emblematic of these attempts was the 1940 exhibition Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art hosted by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York and organized as a coordinated effort between the museum and official cultural institutions in the United States and Mexico. Masterminded by artist, amateur archaeologist, and early enthusiast of Olmec art Miguel Covarrubias, this exhibition provided the model for what Barnet-Sánchez describes as a “collaborative appropriation” of the pre-Columbian past on the part of these two countries.14 The show also served as the direct precedent for the later encyclopedic shows organized by Gamboa, who closely followed the trajectory and general narrative of Covarrubias’s exhibition. Twenty Centuries enlisted the work of figures across a diverse collection of fields. Stirling collaborated with Covarrubias on the exhibition, sending him detailed information and images of colossal heads from his ventures to the Olmec “heartland” before National Geographic published his article and just a few days before the MoMA exhibit opened to the public.15

Readers of Stirling’s National Geographic article offered a striking array of interpretations for his discoveries. In September 1940, for instance, a George Alton from Hawkeye, Iowa, wrote to the National Geographic office, arguing that the five colossal Olmec heads that Stirling had discussed provided decisive evidence of an ancient cosmic and geographic order that existed before the separation of the five continents, and of which the Olmecs were aware. “I know and feel certain,” Alton wrote, “that it was the purpose of the carvers of these heads to mean they knew 5 continents and the Heads faced in the most direct way towards these lands.”16Alton’s hypothesis is not the most fantastical that Stirling’s readers came up with.17 Stirling’s efforts were not merely devoted to exciting the popular imagination, however. In addition to his publications in journals of mass appeal, Stirling also published his findings in academic sources and for p. 17 several decades enjoyed scholarly esteem as one of the primary interpreters of Olmec art and culture in the United States.18

For many years after Stirling’s early writings, the Olmecs re - mained the subject of speculation among scholars of Mesoamerica. By the 1960s, the burden of interpreting Olmec culture in the United States fell on figures such as the Berkeley-based Robert Heizer, an early protégé of Stirling who had first worked on Mesoamerican questions in the context of National Geographic expeditions. Alongside Yale archaeologist Michael Coe, Heizer contributed to the establishment of Olmec archeology as an independent field of study in the United States.19 Like Stirling, Heizer excavated the Olmec site of La Venta several times from the mid- 1950s to the late 1960s. And like Stirling, Heizer not only presented Olmec culture to mass audiences but participated in debates concerning the place of Olmec culture in academic scholarship.

Heizer pursued some of the questions that had long mystified Stirling, particularly the question of how the Olmecs had transported their artifacts. Alongside a letter written in February 1969, for instance, Heizer sent Coe a set of photographic slides he had recently produced that documented the movement of Olmec stone sculptures, including colossal heads, by modern-day inhabitants of the environs of the site of San Lorenzo. In the letter, Heizer alludes to his and Coe’s mutual fascination with the movement of these monoliths and describes his slides as one of only two visual records of the process. The only other source Heizer knew, he tells Coe in the letter, was Sweeney’s catalogue for The Olmec Tradition, a fascinating if not exactly “scientific” publication.20 The movement of Olmec artifacts had puzzled Heizer for some time before this. Four years earlier, in the summer of 1965, Heizer and Howell Williams, a geology professor at Berkeley, had requested funding for a study that would explain the sources of stone for the Olmec monuments, as well as the technology used to move the stones.21 In an article published in Science in 1966, Heizer compares the movement of monoliths in the Old and New Worlds since ancient times, including that of Olmec heads, obelisks, and large stones used to build monumental complexes.22

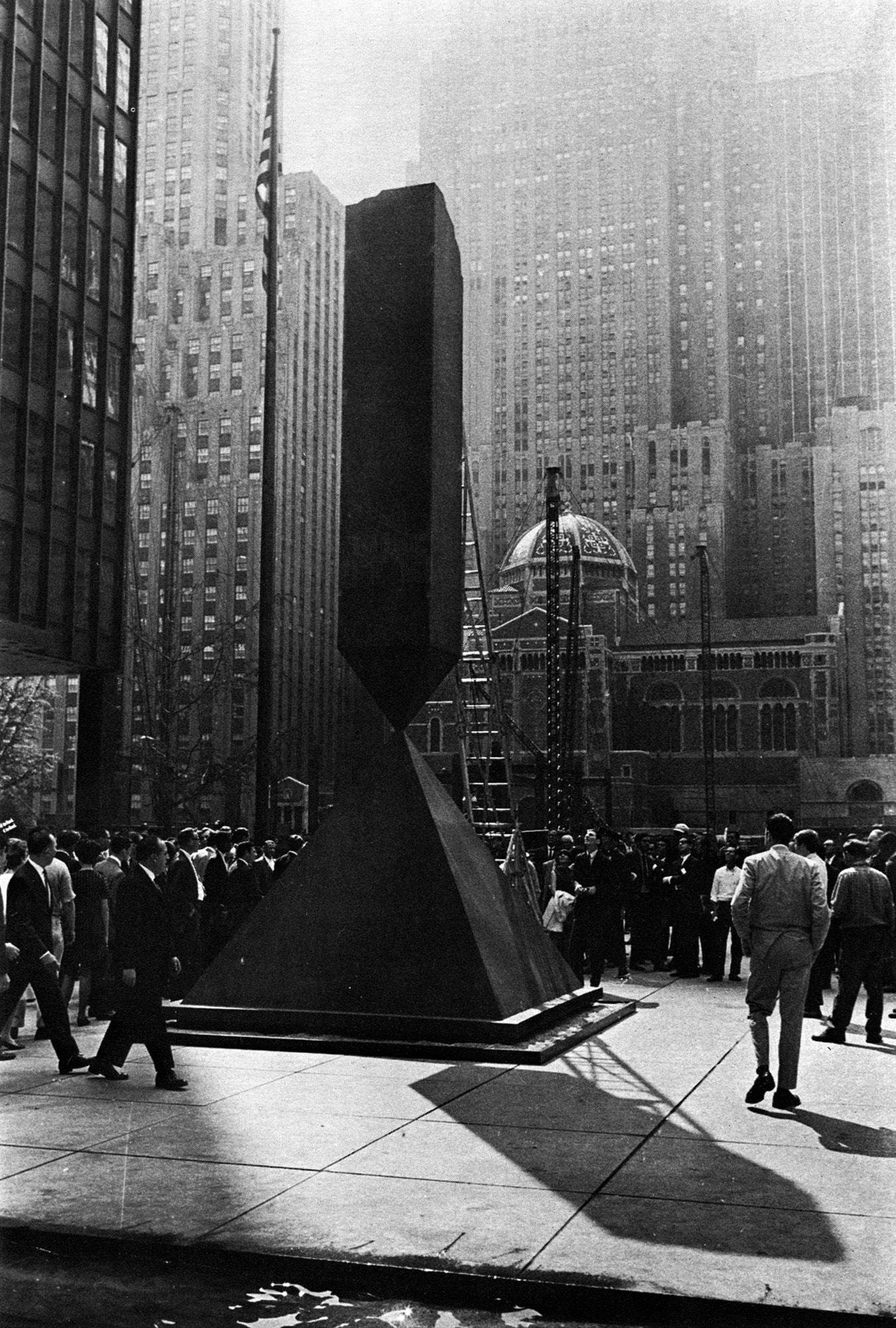

Heizer was aware of the exhibitions of Olmec colossal heads organized in the United States in the early to mid-1960s. In 1967, a group of Heizer’s students at Berkeley produced the first comprehensive publication about the twelve colossal heads known at the time, providing formal analyses of these works as well as archaeological information about them.23 The report paid considerable attention to the visibility of Olmec heads as part of exhibitions in museums and other venues.24 While it accounted for LACMA’s 1963 show and Sweeney’s show in Houston, the report failed to mention the two exhibitions of Olmec heads that had taken place in the context of the 1964-1965 World’s Fair. In a p. 18 March 1968 letter, archaeologist Lee Parsons mentioned these omissions to Heizer, arguing that these displays had been highly significant in introducing Olmec art to mass audiences.25 During the fair’s second season in 1965, two Olmec heads, including San Lorenzo Monument Five, were displayed at the art exhibit Gamboa curated at the Mexican pavilion. Before the exhibit opened, however, Gamboa exhibited one of the heads, San Lorenzo Monument One, in front of Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building in New York as a “public” sculpture on a wooden pedestal designed by Philip Johnson.26

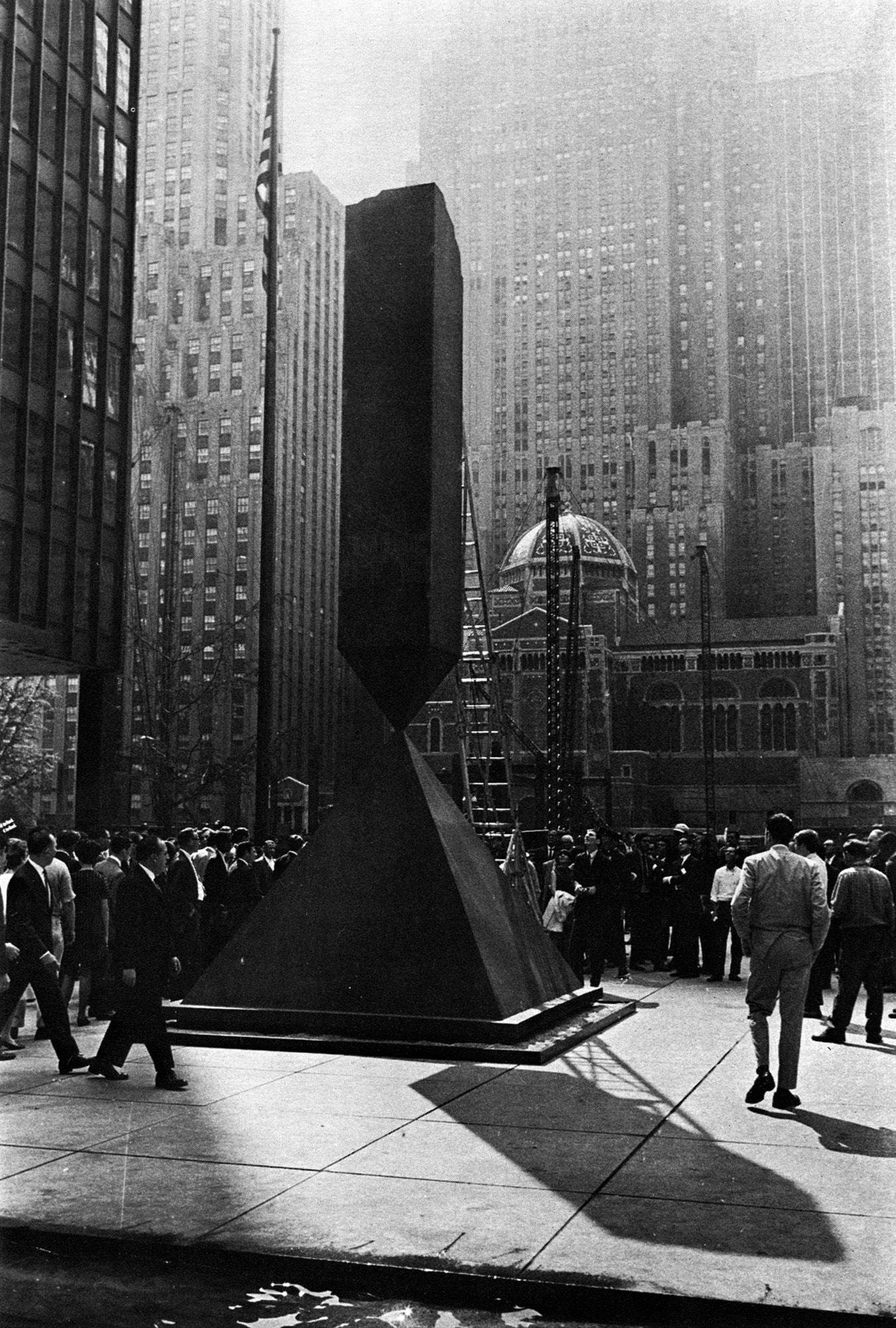

The Seagram intervention served two purposes. Although Gamboa intended it to serve as a prelude to promote the Mexican pavilion’s exhibit at the World’s Fair at an urban area of high visibility in Manhattan, he also promoted it as a gesture of U.S.- Mexican cultural collaboration. Discovered by Stirling in 1947 at the site of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan, San Lorenzo Monument One was one of the largest and heaviest Olmec heads known at the time. The technological challenges that the movement of this colossal head entailed received the lion’s share of media attention. Life took notice of the event, describing the Olmec head shown at Seagram Plaza in its May 28, 1965, edition as the “earliest monumental sculpture found in the Western hemisphere.” To demonstrate the installation process at Seagram Plaza, Life Figure 3 San Lorenzo Monument One on

display at Seagram Plaza, 1965.

As reproduced in Architectural

Forum (June 1965). also presented a large-scale illustration of the heavy monolith being lifted into position by a crane.27

San Lorenzo Monument One on

display at Seagram Plaza, 1965.

As reproduced in Architectural

Forum (June 1965). also presented a large-scale illustration of the heavy monolith being lifted into position by a crane.27

In its account of the same event, Architectural Forum reported that before the head was installed at Seagram Plaza questions were raised about whether the plaza and the midtown Manhattan roads leading to it, including those built over Grand Central Terminal’s train tracks, could support the weight of the Olmec head on a cargo truck. In order to minimize stress to the plaza’s structure and after close consultation with an engineering firm, Gamboa and Johnson decided to place the head on a pedestal made of thick wooden supports and to place this pedestal directly over a supporting column undergirding the structure of the Seagram Building.28 The transfer of the Olmec head from its location at Seagram to the fair was an elaborate incident in its own right. The head was loaded onto a flatbed truck by a p. 19 20 sixty-five-ton crane, much to the surprise of numerous New York City onlookers, who congregated around the event as it unfolded. Moving the head out of Seagram Plaza was estimated to take two to three hours. Although it left Seagram at 9 a.m. on July 9, 1965, the head did not arrive at the fairgrounds until 1 a.m. the next day.29

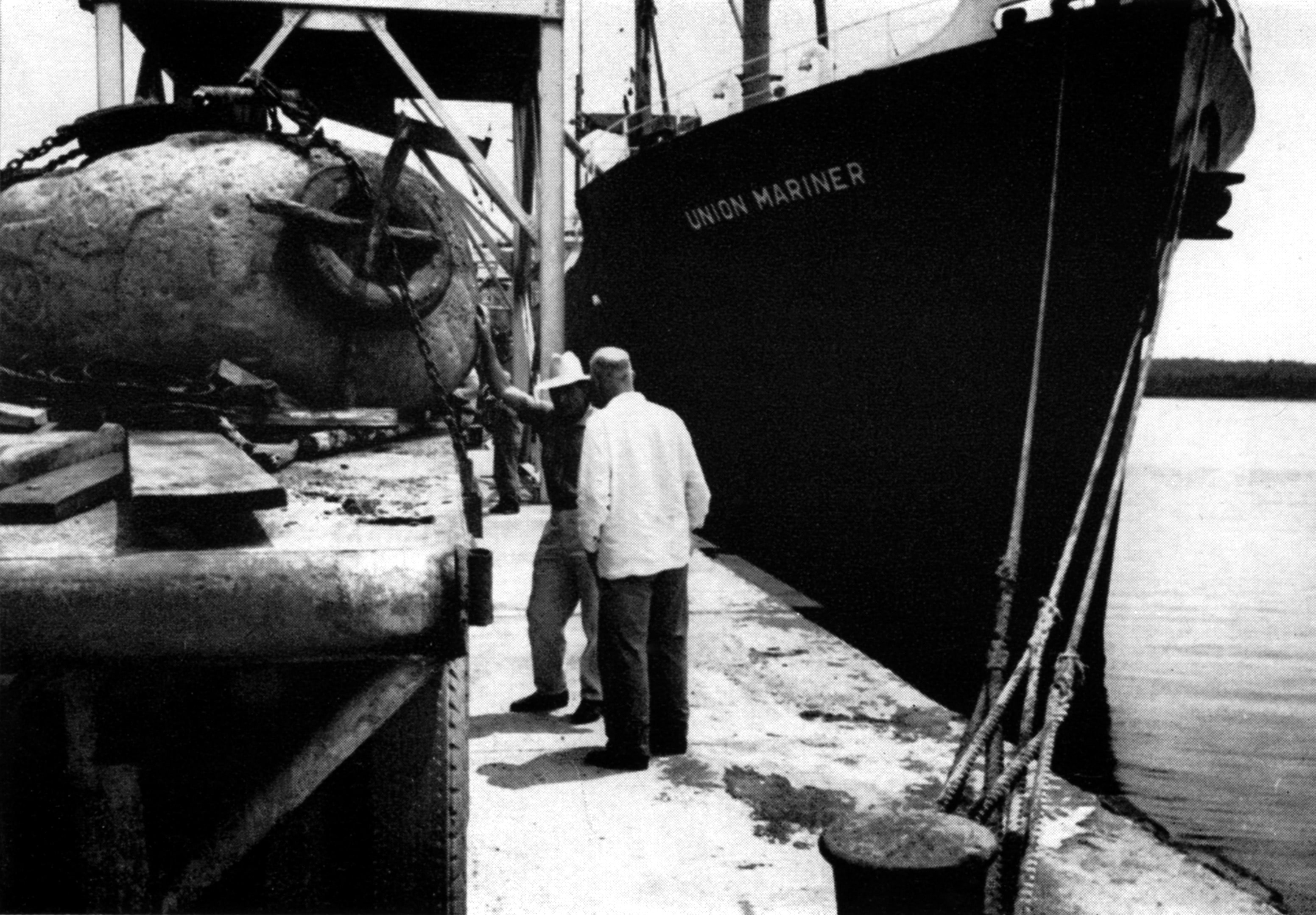

The spectacular movement of this giant head was not the first event of its kind. Sweeney’s show in Houston was the first museum exhibition to present Olmec objects as part of a unified stylistic tradition, and it also had a remarkable history of monolith movement. The show involved another head from the site of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan—Monument Number—and another building by Mies van der Rohe: Cullinan Hall, the museum’s primary exhibition space, a pavilion of steel and glass inaugurated in 1958. Sweeney initially planned to borrow a head from a Mexican museum, but Eusebio Dávalos, then director of Mexico’s National Institute of History and Anthropology (INAH), persuaded him to recover a head from a much less urban location. “Here was a great head,” Sweeney wrote in the catalogue for his show, “a masterwork of early Amerindian art, neglected in the jungle nearly two thousand years… . Why not bring it out for exhibition in Houston, then return it to Mexico City for the National Museum?”30

Strictly speaking, San Lorenzo Monument Two had not been neglected nearly as long as Sweeney claimed, because Stirling had documented it in the mid-1950s. However, the head had never been moved from its discovery location.31 Sweeney traveled to Mexico several times in order to organize the transportation of the head to Houston and also made two trips with documentary filmmaker Richard de Rochemont in order to produce a film

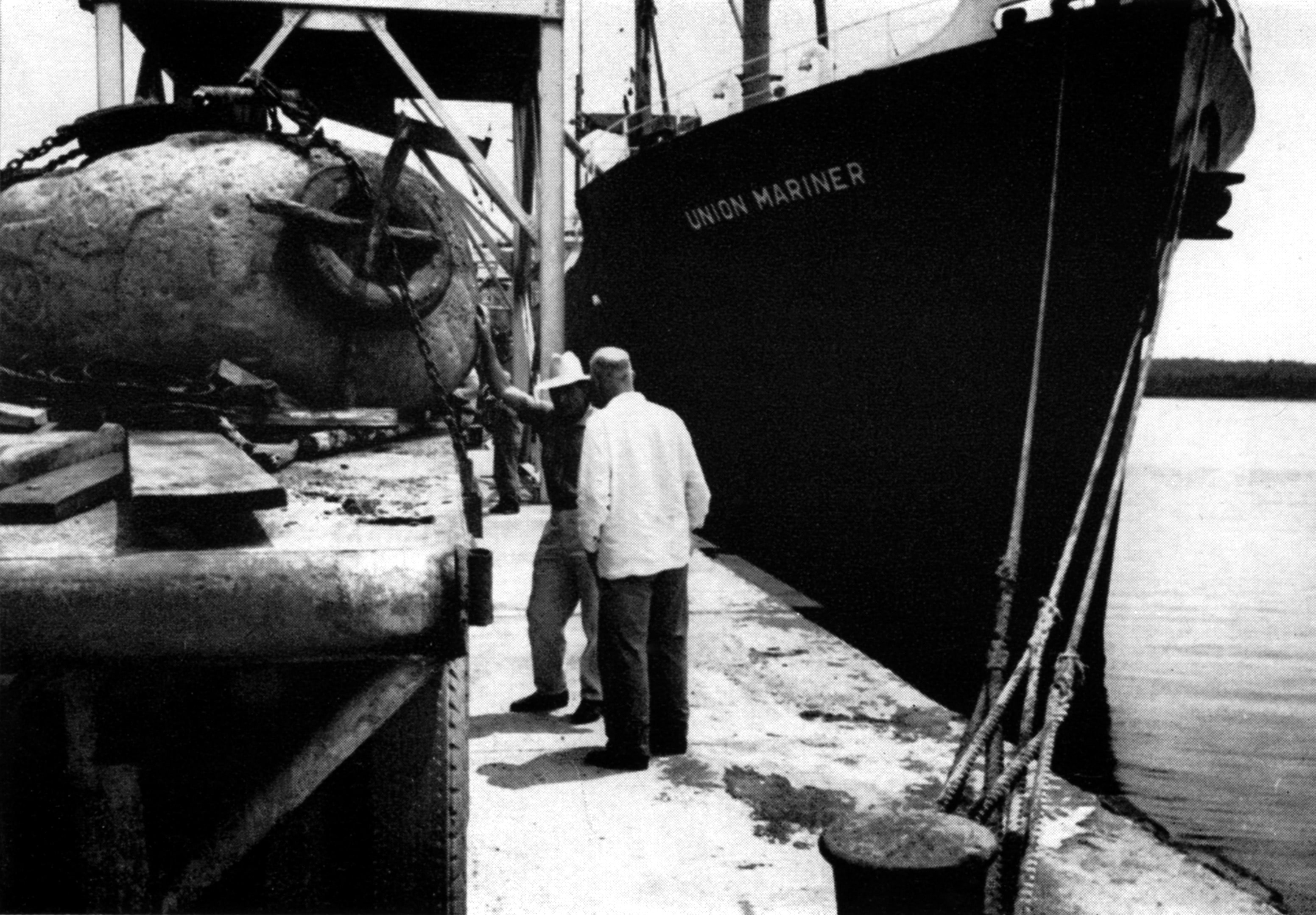

Figure 4 Opposite: “To Houston by Ship.”

From the catalogue for The

Olmec Tradition, Museum of

Fine Arts, Houston, June 18,

1963–August 25, 1963.

Photo: Richard de Rochemont.

RG11:01:02 Publications

Department, Printed Materials,

Exhibition Catalogs, Museum of

Fine Arts, Houston, Archives.

Opposite: “To Houston by Ship.”

From the catalogue for The

Olmec Tradition, Museum of

Fine Arts, Houston, June 18,

1963–August 25, 1963.

Photo: Richard de Rochemont.

RG11:01:02 Publications

Department, Printed Materials,

Exhibition Catalogs, Museum of

Fine Arts, Houston, Archives.

about the expedition. The film connected Sweeney’s and Stirling’s ventures in the Olmec “heartland,” citing the museum director’s readings of the archaeologist’s reports as his primary motivation for the ambitious project and explicitly positioning Sweeney as the heroic continuator of Stirling’s discoveries.32

The catalogue for Sweeney’s exhibition devotes a great deal of attention to the transportation of the head and includes an exhaustive and detailed set of photographs of the many stages of the process. The highlight of the catalogue is the section devoted to the movement of the head, although the actual exhibition included a number of other Olmec artifacts, some of which were just as large and heavy as the moving monolith. The catalogue provides enough details about how the Olmec colossal head was moved to capture the interest of specialists like Heizer and Coe. Beginning with a monolith buried in a jungle setting, the sequence of images in the catalogue illustrates the clearing of forest vegetation in the vicinity of the monolith by numerous local laborers, their creation of a highway, and their transportation of the head, carried first by a trailer truck through the Veracruz jungle and then by ship to Houston from the port of Coatzacoalcos in Veracruz.

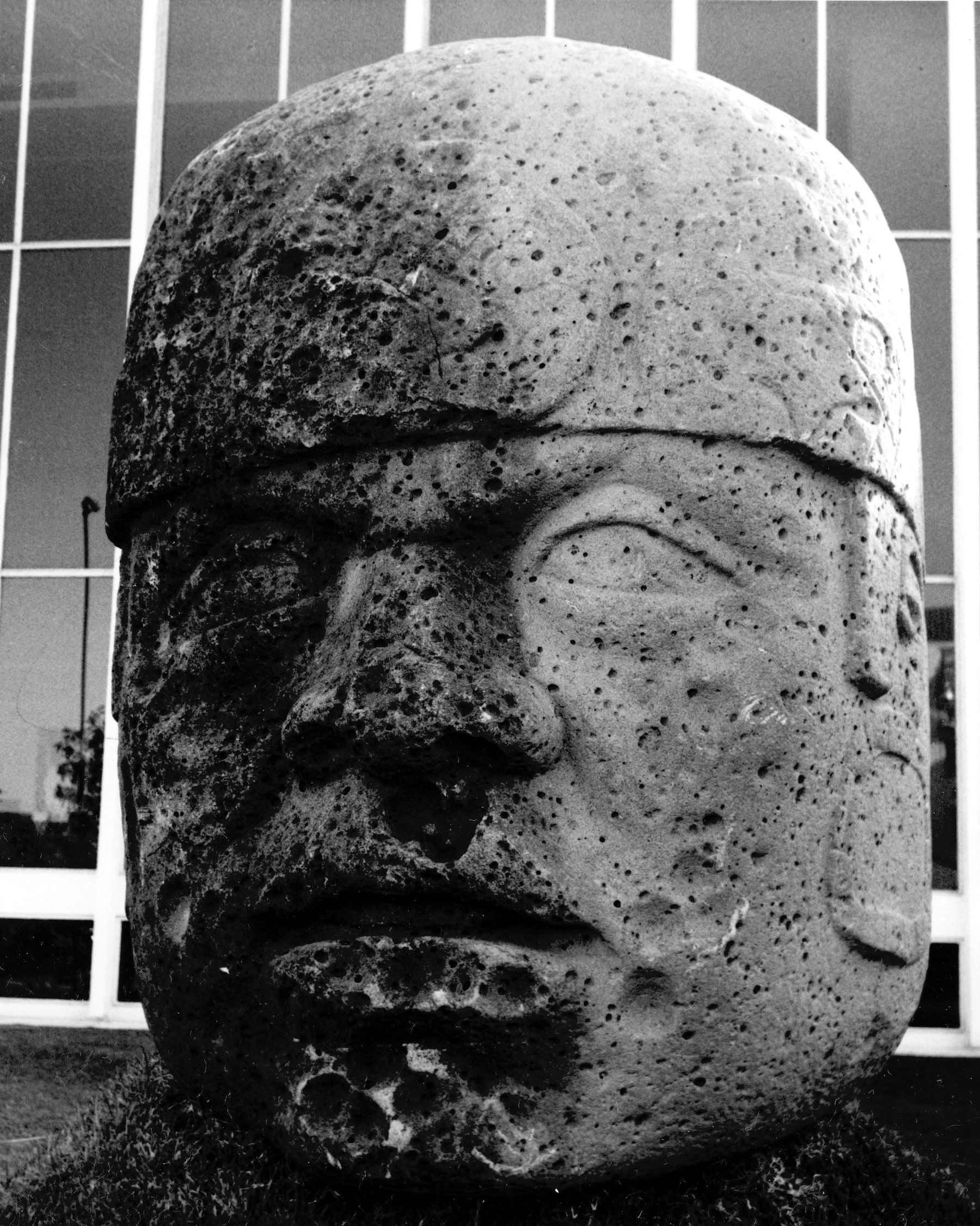

Before they decided to use a trailer, de Rochemont and Sweeney considered other options. In a June 19, 1962, letter, for instance, de Rochemont wonders whether a helicopter could get the job done more efficiently. In making this suggestion, de Rochemont also makes explicit that the real point of the project was not Figure 5 Below: San Lorenzo Monument

Two in front of Cullinan Hall,

Houston, 1963. Installed as part

of the exhibition The Olmec

Tradition, Museum of Fine Arts,

Houston, June 18, 1963–August

25, 1963. Robert F. Heizer Papers,

National Anthropological

Archives, Smithsonian Institution. the head itself but the spectacle of its motion. “I estimate that ‘your’ head,” he writes to Sweeney, “weighs 15 tons… . Biggest known helicopter … lifts 10 tons … Would [Mexican authorities] mind if we cut the head in half?” Although the artistic and archaeological value of the Olmec head was of importance to Sweeney’s exhibition, in de Rochemont’s words, the visual documentation of the massive head’s movement was what truly transformed the film and the exhibition into “an archaeological epic.”33 The triumphant conclusion of the head’s journey led to its installation on top of an earth mound in front of Cullinan Hall. Both the catalogue and the film portray the juxtaposition of the Olmec head’s rugged skin and the reflective surface of Mies’s building as the central incident of the onerous enterprise.p. 21

Below: San Lorenzo Monument

Two in front of Cullinan Hall,

Houston, 1963. Installed as part

of the exhibition The Olmec

Tradition, Museum of Fine Arts,

Houston, June 18, 1963–August

25, 1963. Robert F. Heizer Papers,

National Anthropological

Archives, Smithsonian Institution. the head itself but the spectacle of its motion. “I estimate that ‘your’ head,” he writes to Sweeney, “weighs 15 tons… . Biggest known helicopter … lifts 10 tons … Would [Mexican authorities] mind if we cut the head in half?” Although the artistic and archaeological value of the Olmec head was of importance to Sweeney’s exhibition, in de Rochemont’s words, the visual documentation of the massive head’s movement was what truly transformed the film and the exhibition into “an archaeological epic.”33 The triumphant conclusion of the head’s journey led to its installation on top of an earth mound in front of Cullinan Hall. Both the catalogue and the film portray the juxtaposition of the Olmec head’s rugged skin and the reflective surface of Mies’s building as the central incident of the onerous enterprise.p. 21

| | | | |

De Rochemont and Sweeney wanted to emphasize the ability of their collaboration to create an intense confrontation between ancient artifacts and modernist spaces. This was also the rationale behind Gamboa’s transportation of an Olmec head through the streets of Manhattan and its subsequent installation at Seagram Plaza. Placed in modern display settings, the colossal heads exerted an unsettling influence over their surroundings, exciting intense primitivist fascinations. How the heads’ ability to unsettle viewers in urban contexts operated is best summed up in the catalogue for Gamboa’s 1963 show at LACMA. In his foreword to the catalogue, Richard Brown, then LACMA’s director, describes the aesthetic impact that San Lorenzo Monument Five had over him after he encountered the monolith in the most unexpected of places, the metropolitan capital of the nineteenth century:

On a lovely summer morning in 1962, while strolling toward the Pont Alexandre, reveling in all the refined beauty that makes Paris “home” to every truly civilized man, I was suddenly stunned to encounter a six-ton Olmec head on the steps of the Petit Palais. The poster told me that inside was the great exhibition of Mexican art, about which I had heard so much during the previous four years while it had been touring the major capitals of Europe… . I knew this was the exhibition that had to be seen in Los Angeles.34

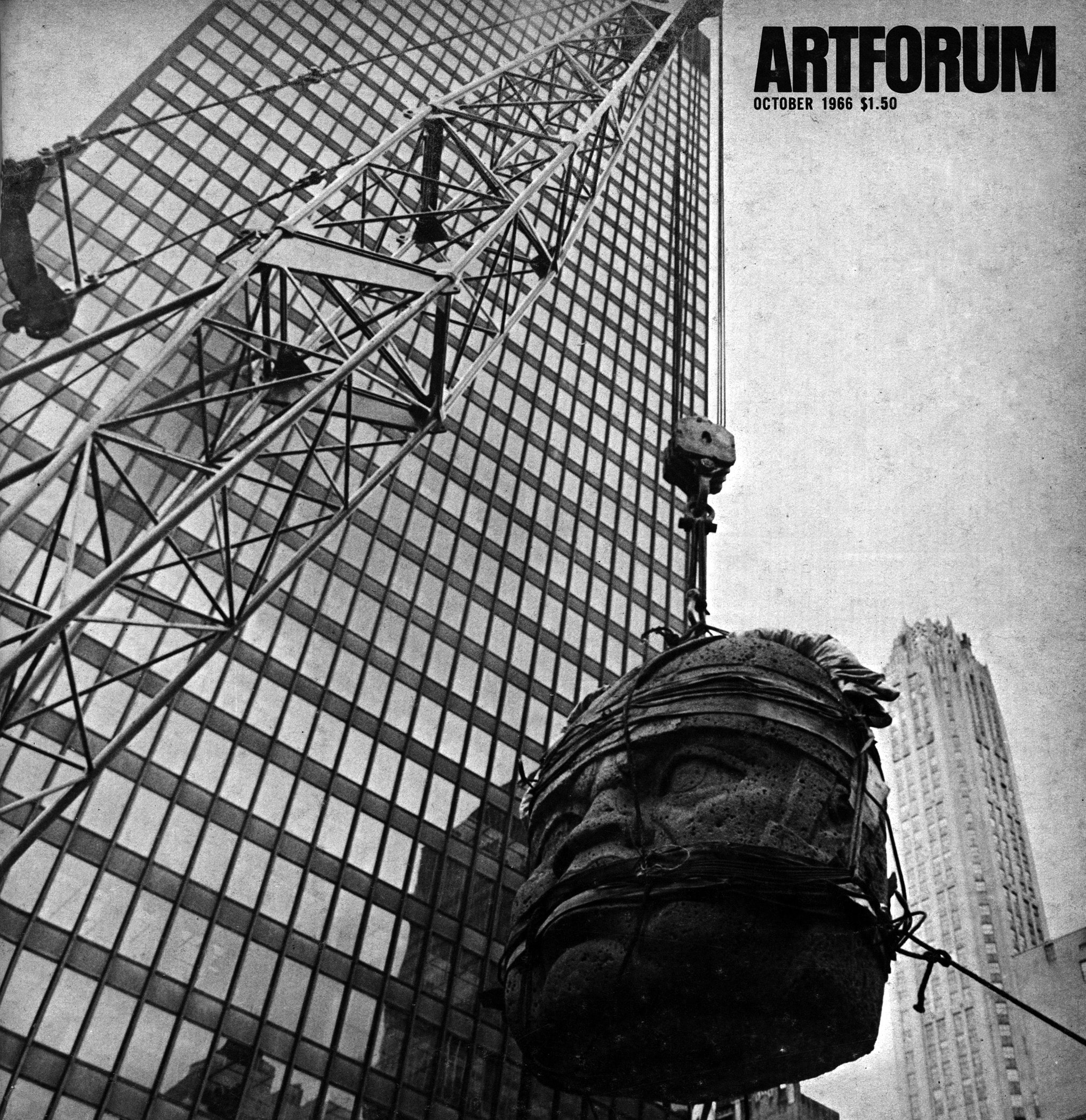

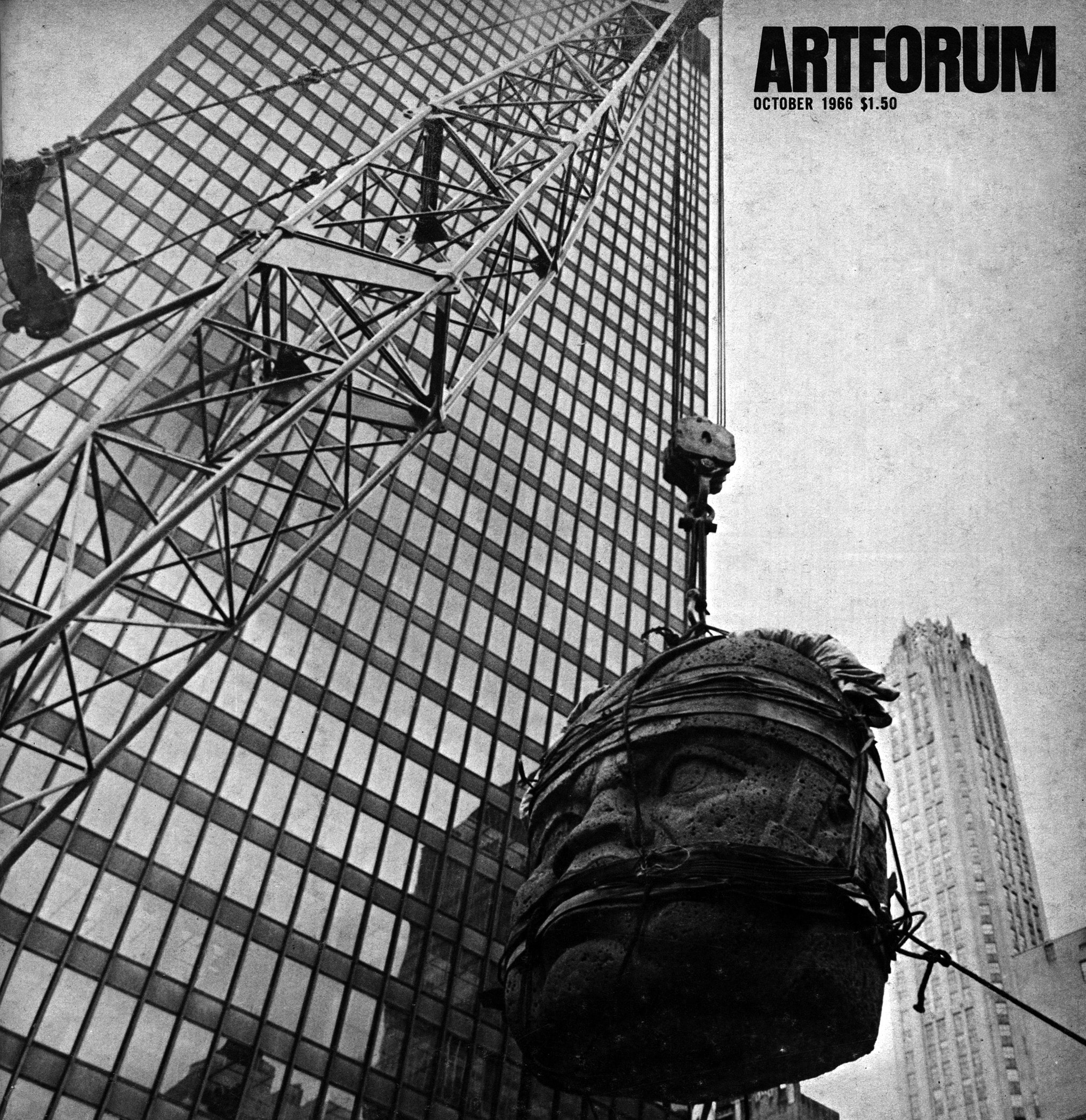

Olmec heads managed to captivate not only museum directors. An intense interest in the revelatory power of the heads also informed their reception among artists and critics. For instance, the cover of the October 1966 issue of Artforum is devoted to the installation of San Lorenzo Monument One at Seagram. Ostensibly, the doubling of time is the cover’s primary theme. In the Artforum image, the heavy Olmec head is suspended in Figure 6 Opposite: Cover of

Artforum, October 1966. midair by a crane and hovers in front of the steel-and-glass skin of Mies’s skyscraper. The image presents the event as an evocative clash of ancient and modern surfaces and materials, a clash so striking that it seems to turn the relationships of scale between sculpture and skyscraper on their head. Because of the photograph’s framing, which displays the monolith’s movement from below, Seagram seems to soar toward the sky looking light and smooth as ever, while the colossal head’s heaviness is emphasized, looming as it does over the viewer. More than sculpture or skyscraper, the image p. 22 attempts to render dramatic and spectacular the distance—temporal, material, and cultural—between the two objects.

Opposite: Cover of

Artforum, October 1966. midair by a crane and hovers in front of the steel-and-glass skin of Mies’s skyscraper. The image presents the event as an evocative clash of ancient and modern surfaces and materials, a clash so striking that it seems to turn the relationships of scale between sculpture and skyscraper on their head. Because of the photograph’s framing, which displays the monolith’s movement from below, Seagram seems to soar toward the sky looking light and smooth as ever, while the colossal head’s heaviness is emphasized, looming as it does over the viewer. More than sculpture or skyscraper, the image p. 22 attempts to render dramatic and spectacular the distance—temporal, material, and cultural—between the two objects.

The October 1966 issue of Artforum also features an article discussing some of the ways in which the Olmec head displayed at Seagram had impacted the work of New York-based sculptors. In the article, Irving Sandler provocatively claims that the installation of the head at Seagram had taught artists Al Held and Ronald Bladen fundamental lessons about the creation of monumental sculptures, that it taught them how to “mak[e] things look larger than they are.”

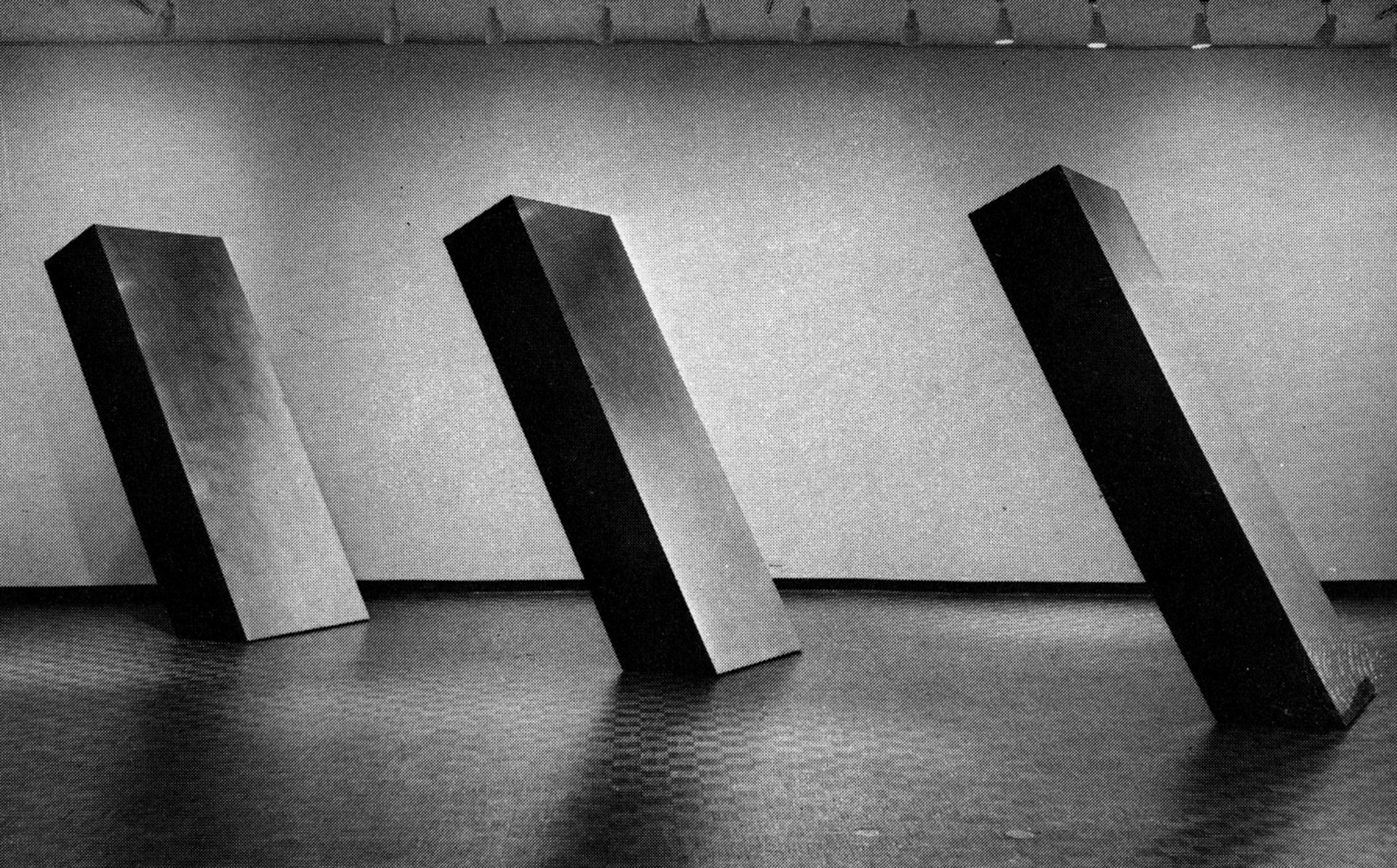

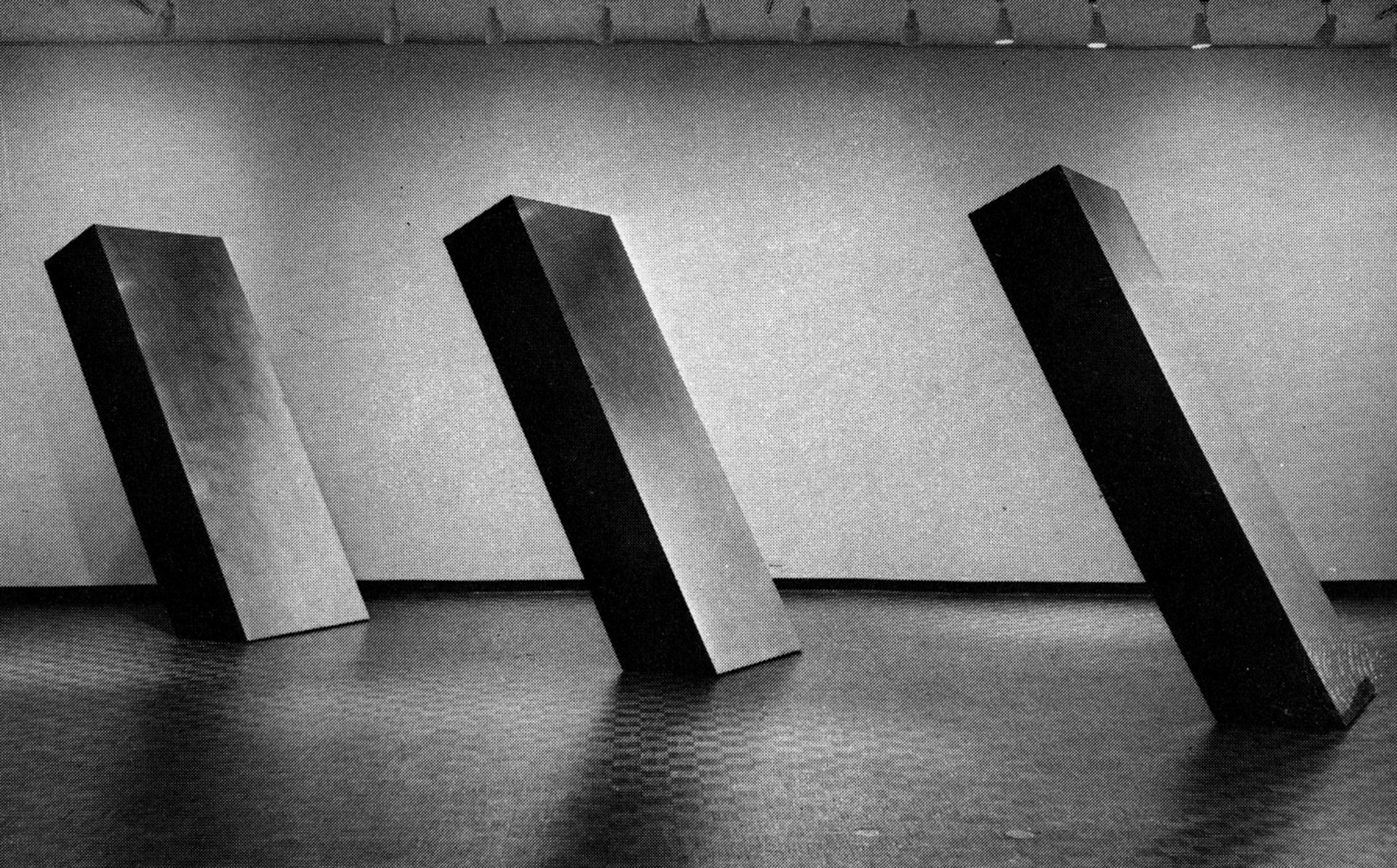

“It was a large sculpture,” Sandler writes about San Lorenzo Monument One, “but size alone could not account for the way it dwarfed the surrounding skyscrapers and made them look cardboard thin.”35 Sandler also argues that the Olmec head and its base designed by Johnson provided the model for Bladen’s Untitled sculpture, whose first version, made in 1965, consisted of three pieces of slanted heavy wood aligned horizontally. Based on a recomposition of the wood components of the sculpture’s pedestal, Untitled also emphasizes the rugged and heavy materials out of which it was made, as well as the strict technical calculations that prevent the pieces of wood, seemingly held upright in precarious balance, from collapsing. In 1966, Bladen produced a version of this sculpture in painted and burnished aluminum, retaining the formal makeup and proportions of the wood original.36

Sandler’s reading of San Lorenzo Monument One as a revelatory influence on the development of abstract sculpture necessitated the full uprooting of the Olmec head from its archaeological context. Gamboa’s exhibition at Seagram facilitated this reading. Whereas at the Mexican pavilion at the New York World’s Fair Gamboa positioned San Lorenzo Monument One and San Lorenzo Monument Five at the origin point of a curatorial narrative of “national” Mexican culture, at the Seagram Plaza he exhibited the first of these colossal heads as an isolated artwork,

Figure 7 Below: Ronald Bladen.

Untitled, 1966. © The Estate of

Ronald Bladen, LLC/Licensed

by VAGA, New York. p. 23

Below: Ronald Bladen.

Untitled, 1966. © The Estate of

Ronald Bladen, LLC/Licensed

by VAGA, New York. p. 23

with minimal historical or cultural contextualization.37

Sweeney was equally adamant about showing Olmec artifacts in almost total isolation from “external” information.38 In his Houston show, he had smaller Olmec objects enclosed in clear glass cases. The larger objects in the exhibition rested on stark white, fully abstract supports. The rugged surfaces of these artifacts contrasted with the polished terrazzo floor of Cullinan Hall, as well as with its stark white walls, which were left empty. In an effort to present the Olmec objects in even more minimal fashion in the exhibition catalogue, Sweeney had photographic proofs of his installation cropped to cut out the floor and ceiling of Cullinan Hall, leaving visible only the Olmec objects against the blank background of the building. In his exhibitions of modern art, Sweeney strived for a similar kind of spatial layout, one in which the formal language of artworks dissolved into the universalizing, Miesian space of Cullinan Hall.39

Gamboa’s display of an Olmec head as a “public” artwork at Seagram had a number of precedents in Mexico, but these earlier displays of colossal heads had not sought to disengage them from the contexts of their discovery.40 In 1960, curators at the Anthropological Museum at Xalapa, Veracruz, had installed San Lorenzo Monument One on top of a mound of earth alongside a number of other heavy monoliths surrounding the museum building. The mound at Xalapa provided a model for Sweeney’s installation of San Lorenzo Monument Two in front of Cullinan Hall. Since 1950, the head known as Nestepe Monument One had been an essential feature of a public square in the city of Santiago Tuxtla in Veracruz alongside other Olmec monoliths on concrete pedestals.41 A replica of La Venta Monument One, one of the heads Stirling excavated during his 1939 expedition, had been installed at a public square in the city of Tabasco, not far from the Figure 8 Installation views of The Olmec

Tradition, Museum of Fine Arts,

Houston, June 18, 1963–August

25, 1963. Photo: Hickey and

Robertson. Museum of Fine Arts,

Houston, Archives. site where the original was found. Before the Seagram installation, Gamboa, as part of his traveling Masterworks exhibition, had installed colossal heads in public spaces at various international locations, including LACMA and the Petit Palais in Paris.

Installation views of The Olmec

Tradition, Museum of Fine Arts,

Houston, June 18, 1963–August

25, 1963. Photo: Hickey and

Robertson. Museum of Fine Arts,

Houston, Archives. site where the original was found. Before the Seagram installation, Gamboa, as part of his traveling Masterworks exhibition, had installed colossal heads in public spaces at various international locations, including LACMA and the Petit Palais in Paris.

In a sense, nothing about Gamboa’s installation of an Olmec head at Seagram was resolutely new. In more ways than one, Sandler’s interpretation of the head as the source of inspiration for an artistic breakthrough of sorts was nothing new either. As Michael Leja demonstrates, the appropriation of the supposedly “primitive” aspects of ancient p. 24 and indigenous art defined the practice of the generation of New York artists and critics with whom Sandler came of age during the 1940s. As pre-Columbian art from Mexico gained visibility in New York through events like Twenty Centuries of American Art, artists such as Barnett Newman, Adolph Gottlieb, and Mark Rothko drew various kinds of inspiration from pre-Hispanic works from several parts of the Americas alongside works from other ancient and indigenous artistic traditions.42

Newman was particularly interested in pre-Columbian stone sculpture from Mexico, and he organized a show of such objects at the Betty Parsons Gallery in May 1944. In a text written for the show, Newman argues that by “looking at them as works of art rather than as the artifacts of history or ethnology” (precisely the way the Seagram and Houston exhibits presented the Olmec heads), “we can grasp their inner significance.”43 Newman also regarded the artistic appreciation of pre-Columbian art in the United States as diplomatically significant. He describes pre- Columbian art as “a large body of art which should unite all the Americas since it is the common heritage of both hemispheres.” Rather than serve to strengthen the geopolitical relations between the governments of different countries, as cultural bureaucrats in Mexico and the United States argued it would at the time, this connection was seen by Newman as potentially subversive because it could unite the peoples of the Americas in challenging these governments’ authority.44

| | | | |

Despite the familiarity of artists and critics in New York with pre- Columbian art from Mexico, the urban presence of an Olmec head at Seagram did bring something new to the mid-1960s Figure 9 Barnett Newman. Broken

Obelisk, 1963/1967. © The Barnett

Newman Foundation/Artists

Rights Society (ARS), New York. New York art world, where practices of “public art” would soon rise to prominence. In the fall of 1967, the New York City Administration of Recreation and Cultural Affairs commissioned a unique kind of exhibition titled Sculpture in Environment. As part of the exhibition, which lasted through October, twenty-four artists installed large-scale sculptures on significant sites throughout the city. In his introduction to the exhibition catalogue, Sandler claims that sculpture’s increasing desire for a sense of “monumentality, not of size alone but of the kind of scale that causes forms to p. 25 appear larger than they are,” had motivated the exhibition. This was the all-important feature that, in his view, the Olmec head shown at Seagram so strikingly possessed. The quest for monumentality, Sandler argues, accounted for the ambitious curatorial attempt to “free” the sculptures in public space in search of a “new” sculptural tradition not limited by the boundaries of the artist’s studio.45

Barnett Newman. Broken

Obelisk, 1963/1967. © The Barnett

Newman Foundation/Artists

Rights Society (ARS), New York. New York art world, where practices of “public art” would soon rise to prominence. In the fall of 1967, the New York City Administration of Recreation and Cultural Affairs commissioned a unique kind of exhibition titled Sculpture in Environment. As part of the exhibition, which lasted through October, twenty-four artists installed large-scale sculptures on significant sites throughout the city. In his introduction to the exhibition catalogue, Sandler claims that sculpture’s increasing desire for a sense of “monumentality, not of size alone but of the kind of scale that causes forms to p. 25 appear larger than they are,” had motivated the exhibition. This was the all-important feature that, in his view, the Olmec head shown at Seagram so strikingly possessed. The quest for monumentality, Sandler argues, accounted for the ambitious curatorial attempt to “free” the sculptures in public space in search of a “new” sculptural tradition not limited by the boundaries of the artist’s studio.45

The installation of one of these “new” sculptures in a public space directly engaged the recent memory of Gamboa’s installation at Seagram. At Seagram Plaza in the same location where Gamboa had displayed San Lorenzo Monument One only two years earlier, Newman installed the first iteration of his Broken Obelisk (1963-1967), a twenty-foot-high sculpture cast out of Cor-Ten steel.46 An ironic commentary on the obelisk’s status as a canonical monumental form, Newman’s work comprises a pyramidal base and an apparent fragment of a broken obelisk. These two components meet at their pointy edges, as if suspended in precarious balance. Cor-Ten steel explicitly blurred the visible boundaries between “natural,” organic textures and smooth, industrially produced ones. This material, which showcases its own decay and aging, mirrors the porous surface of the basalt out of which San Lorenzo Monument One is made and gives Newman’s sculpture a “primitive,” rough finish.

In her review of Sculpture in Environment, Lucy Lippard argues that most of the sculptures placed in public spaces throughout the city “looked like nothing so much as evicted furniture.” Newman’s work was the only “first-rate” work in the entire exhibition. The sculpture succeeded not only because it was noticeable, “a necessary prerequisite of public art,” but because the combination of its large scale, rugged surface, and highly visible site of installation “provide an inescapable impact or ‘presence,’ an indefinable quality of much recent nonrelational work which Newman’s sculpture has inherited from his painting.”47 “Primitive” art had been one of the primary iconographic sources for Newman’s nonrelational painting since the 1940s, and his contribution to Sculpture in Environment continued this dialogue by engaging more than just the scale, rugged texture, and precise site of installation of San Lorenzo Monument One. The narrative crux of Newman’s sculpture consists of its combination of implied motion and stasis, two variables that lent the Olmec monolith, as installed by Gamboa, much of its expressive power. Not only does the dynamic interaction between the sculpture’s physical components hint at movement, but Broken Obelisk also alludes to the movement of monoliths thematically.

Since Roman times, obelisks, objects rife with talismanic meaning, have been moved from their original locations in Egypt into Western urban centers as part of campaigns of territorial p. 26 conquest. When displaced and reinstalled in these foreign centers, the obelisks stand out as radically anticontextual, objects out of tune with their urban surroundings yet capable of reinventing their meanings. The Parisian Place de la Concorde is a case in point. In 1836, King Louis Philippe I ordered that an obelisk gifted to his government by Egypt’s viceroy be placed at the center of this square. Founded in 1755, the square was originally named Place Louis XV in honor of the reigning monarch, and showcased a statue of the king that was toppled and replaced by a guillotine during the Revolution, at which time the square served as the site of numerous public executions. The obelisk installed in 1836 was thus aimed at recasting the square’s violent history in terms emblematic of post-Revolutionary social harmony and cosmopolitan imperialism. Transporting this artifact was an impressive engineering feat commemorated in the obelisk’s pedestal. Moved by hundreds of workmen through a complex system of heavy ropes, wires, and pulleys, the obelisk’s displacement across water and land was accomplished by overcoming numerous seemingly insurmountable obstacles.48

In 1881, an obelisk was placed in Central Park in New York as part of a much-publicized political exchange between U.S. and Figure 10 Michael Heizer. Dragged Mass

Displacement, 1971. Photo courtesy

the Detroit News Archives. Egyptian authorities. The monument reportedly almost broke while being loaded onto the steamship that would transport it across the Atlantic.49 San Lorenzo Monument One can be understood as the mid-1960s equivalent of these moving obelisks, an object from a still-mysterious ancient culture that had traveled across national borders as part of a diplomatic exchange between the United States and Mexico. Although the Olmec head was not permanently installed at Seagram, its movement was no less meaningful on account of its mass-mediated dissemination.

Michael Heizer. Dragged Mass

Displacement, 1971. Photo courtesy

the Detroit News Archives. Egyptian authorities. The monument reportedly almost broke while being loaded onto the steamship that would transport it across the Atlantic.49 San Lorenzo Monument One can be understood as the mid-1960s equivalent of these moving obelisks, an object from a still-mysterious ancient culture that had traveled across national borders as part of a diplomatic exchange between the United States and Mexico. Although the Olmec head was not permanently installed at Seagram, its movement was no less meaningful on account of its mass-mediated dissemination.

Positioned next to the Seagram Building and its surrounding skyscrapers, the colossal head stood in jarring contrast to its surroundings. The head’s much-promoted transportation process was cumbersome on account of its scale, weight, and rugged materials, and its physical and cultural condition was thus fragile and contingent, not unlike that of p. 27 the fragmented obelisk to which Newman’s sculpture alludes more literally. Aesthetically emancipated as a result of its uprooting from its original context of discovery, the Olmec head was also out of sorts in its imposed setting of “modern” display. Thus, contained in Newman’s sculpture was the simultaneous celebration of the displacement of monoliths to serve official cultural agendas and a critique of the instrumentalization of these objects that such procedures inevitably entail.50

While she does not point to the specific dialogue between Broken Obelisk and San Lorenzo Monument One, in her review Lippard does discuss the strong primitivist bent of works by Newman, Bladen, Tony Smith, and Robert Morris that were included in Sculpture in Environment. These sculptors’ attempts to redefine monumentality in sculpture, she claims, were predicated on an appropriation of the presumed stoicism of ancient, “primitive” forms. The objects these sculptors attempted to evoke included “the minarets, mounds, mastabas, obelisks, ziggurats, menhirs of ancient cultures.” These were all components of the reservoir of “primitive” forms that these and other artists had long tapped into and that also included pre-Columbian art from Mexico. Lippard also argues that among artists of the mid-1960s this interest was imbricated with “the idea of archeology itself, the hidden or enclosed, the complex conceptual or intellectual point buried in an impressive mass of purely physical bulk and monumentality.” In addition to proving formative to the development of “public” art trends, this particular interest defined the creation of early earthworks, not least those whose production involved actual excavation.51

The intimate connection between primitivist sensibilities and the production of earthworks and “public” sculptures has not been emphasized enough by scholars. For example, in her survey of the rise of earthworks and other land art interventions, Suzaan Boettger demonstrates that Sculpture in Environment was tied to an often contentious dialogue among city administrations, artists, and critics who debated the role of public sculpture in New York and other U.S. cities in the late 1960s. Yet, despite Sandler’s involvement with the groundbreaking show and Newman’s longstanding interest in pre-Columbian art, as well as the powerful relationship between Broken Obelisk and the installation of San Lorenzo Monument One at Seagram Plaza, Boettger does not include any of the episodes examined here as part of her otherwise informative analysis.52

Among the more recent breakthroughs in the study of the emergence of land art is the acknowledgment of the close interrelation between its various trends and public art interventions.53 Sculpture in Environment is only one of several exhibitions that propelled this period of experimentation forward.54 Michael p. 28 Heizer’s early oeuvre is situated at the precise intersection of these practices, and the irruption of Olmec heads into the artistic scenes of New York and Los Angeles must be considered significant formative events vis-à-vis his work during the mid- to late 1960s. The work that most directly engages these events is his Dragged Mass Displacement of 1971. Upon a commission by the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) in 1969, Heizer orchestrated the movement of a monolith through an empty lot next to DIA’s main building. Gathering crowds of spectators, the seemingly futile event, which yielded a great deal of debris and was eventually decommissioned because of public outcry over its onerous production, elaborates a powerful critique of modern urbanism.

The work presciently contests one of urbanism’s core operative assumptions: the economic, discursive, and ideological opposition between natural and urban spaces. Dragged Mass Displacement plants itself firmly in the unstable middle ground between these domains. As Julian Myers argues, the work deconstructs the concept of urban space on material and conceptual levels by forcing the ground to reappear through the slow and destructive motion of a monolith, which effectively strips away urbanization’s effects from a parcel of earth as a crane drags it. Myers argues that by zeroing in on the specifics of its urban setting Heizer’s intervention also denounces the racially segregated fabric of Detroit, one of the cities in the United States where urban unrest was most significant in the late 1960s.55

Nevertheless, Heizer’s interest in forcibly making an inscription Figure 11 Michael Heizer.

Levitated Mass, 2011–12.

Photo courtesy Greg Polvi. p. 29 on the ground and moving a large-scale monolith in Dragged Mass Displacement is also directly tied to the archaeological concerns that dominated his father’s practice during the mid- to late 1960s. This relationship has been almost wholly ignored, and most writings on Heizer’s work have focused only on superficial formal relationships between his work, especially his large-scale earthworks produced in remote locations, and pre-Columbian architectural sites.56 However, this interrelation far exceeds purely formal matters and deserves more careful attention.

Michael Heizer.

Levitated Mass, 2011–12.

Photo courtesy Greg Polvi. p. 29 on the ground and moving a large-scale monolith in Dragged Mass Displacement is also directly tied to the archaeological concerns that dominated his father’s practice during the mid- to late 1960s. This relationship has been almost wholly ignored, and most writings on Heizer’s work have focused only on superficial formal relationships between his work, especially his large-scale earthworks produced in remote locations, and pre-Columbian architectural sites.56 However, this interrelation far exceeds purely formal matters and deserves more careful attention.

Like Newman’s Broken Obelisk, Dragged Mass Displacement focuses, albeit with different intentions, on the impact radically anticontextual objects can exert on the fabric of a city. Unlike Newman, Heizer was relatively uninterested in the talismanic attributes of “primitive” sculpture or its potential to provide public sculpture with the kind of experiential je ne sais quoi that Lippard and other critics of the 1960s highly praised. Heizer was instead more engaged with the specific discursive conditions under which uprooted monoliths operate when they are transported from one place to another. Arguably, with Dragged Mass Displacement he was specifically referring to recent events of this kind.

The mass-mediated dimension of Dragged Mass Displacement, which was at once a concrete intervention and an ephemeral but avidly documented event, harks back to the spectacular movement of monoliths that defined Gamboa’s and Sweeney’s operations just a few years earlier. These events were themselves continuations of the archaeological fascination with the movement of colossal Olmec heads that had dominated specialists’ concerns since Stirling’s expeditions. Like Heizer’s intervention, these events were almost wholly constituted in the discursive space of media-based dissemination. And as in the case of these exhibitions, the disruptive spatiotemporal effects of moving monoliths are effectively Dragged Mass Displacement’s primary theme. However, an even more specific connection exists between Heizer’s early interventions and these bombastic exhibitions: During the late 1960s Michael Heizer and Robert Heizer began collaborating on a number of interventions in which archaeological and sculptural practices coalesced.

Writing to fellow archaeologist Philip Drucker in August 1968, Robert Heizer seems remarkably unenthusiastic about the prospect of writing a new book about the Olmecs. Heizer admits to having been “mostly occupied not with archaeology, but [with] Michael’s new art, which involves long trips in 4-wheeled pickups to dry playas where considerable digging is done.”57 Writing to Drucker a month later, Heizer discusses his increasing involvement with his son’s experiments. “Mike has been busy with his ground art project. He and I made a two day trip to Massacre Lake, in Nevada p. 30 just south of the Oregon border, and made a beauty [Isolated Mass/ Circumflex (1968)].”58

The last of Heizer’s nine Nevada Depressions,Isolated Mass/ Circumflex consists of a foot-wide trench dug up in the shape of a loop on a barren landscape. Its labor-intensive production yielded six tons of displaced earth and presaged the kinds of larger-scale and now canonical works that Heizer would complete in the following decades in similarly remote locations.59 Like many of these works, the Depressions are formally and thematically based on interactions between positive and negative space. Heizer produced them by manipulating his sites of intervention, making literal incisions on the earth, and reaccommodating rocks and other landscape formations in machine-made trenches. Tied to the expansion of sculpture’s “field” of operation at the time, Heizer’s interventions also critique archeology’s disciplinary assumptions.60 Working alongside an active Olmec archaeologist, his own father, Heizer literally reenacted the archaeological practice of digging in the ground as a means to acquire historical knowledge. Yet by refusing any easy legibility as acts of intellectual inquiry, the Depressions call into question the ideological premises behind any archaeological intervention.

| | | | |

Michael Heizer’s extended work with LACMA from 2010 to 2012 pays belated homage to these collaborations with his father, engaging a line of sculptural explorations that can be traced back to the years of “discovery” of Olmec art in the United States. Heizer’s installation of Olmec artifacts in Renzo Piano’s Resnick Pavilion makes at least one reference to Newman’s Broken Obelisk and its relationship to the Seagram site. Heizer’s stands of Cor-Ten steel evoke Newman’s use of the same material, as well as the common history that Newman’s sculpture shares with Gamboa’s installation. Gamboa’s installation at Seagram, in turn, shares a common institutional history of early display of Olmec art with LACMA, where one of his moving Olmec heads was shown in the 1960s. And as with Gamboa’s installation and Newman’s intervention, in Heizer’s 2010 installation the doubling of time is again staged through the confrontation between ancient, monumental, and “anticontextual” sculptures and a building defined, like Seagram and Cullinan Hall, by the modernist languages of steel and glass.

And yet, the resonances between Heizer’s recent work and the era of “discovery” of Olmec art in the United States are even more significant. In addition to the creation of the Cor-Ten steel stands and the exhibition environment for Olmec monoliths in 2010, Heizer also organized the transportation of a large-scale p. 31 monolith to LACMA during the summer of 2012, restaging episodes in the history of Olmec artifacts. The work, Heizer’s Levitated Mass, is structured around the transportation of a 340- ton boulder “discovered” via an explosive blast in a quarry in Riverside, California. If displays of Olmec heads in the early 1960s purposefully excised their cultural contexts of production and discovery, here Heizer exaggerates this gesture by selecting an object that has no ostensible “cultural” profile. The monolith’s perceived worth, as Heizer makes explicit, is exclusively derived from its large size.61 “If all goes according to plan,” the Los Angeles Times reported in May 2011, “that boulder will make a seven-day journey in August from the quarry to the museum’s Miracle Mile location on a specially designed 200-wheel truck. There, it will rest on two concrete rails lining a 15-foot-deep trough, as the museum’s newest sculpture.”62 The massive boulder did make the trip, transitioning from geological curiosity to objet d’art in the process.

Heizer traces the genesis of Levitated Mass to sketches from 1969 that are contemporary with his nine Nevada Depressions and Dragged Mass Displacement, works with which the completed intervention shares obvious thematic and procedural ties. But beyond Heizer’s own oeuvre, Levitated Mass also offers glimpses of other significant incidents from the mid- to late 1960s. Installed at LACMA, Heizer’s imposing monolith hovers over visitors who walk underneath it through the passageway over which it is suspended, which is encircled by a line of Cor- Ten steel embedded in the earth. With the monolith positioned in seemingly unsteady balance over this passageway, this intervention harks back to the tectonic qualities and materials of sculptures such as Newman’s Broken Obelisk or Bladen’s Untitled, which emphasize the delicate technical balance that prevents their heavy components from collapsing. In addition, experiencing the monolith by walking through the passageway underneath it evokes not only the experience of many of Heizer’s other renowned works but the experience of the actual excavation trenches through which archaeological artifacts are studied.

As with the case of Sweeney’s and Gamboa’s projects during the 1960s, Levitated Mass focuses primarily on the technological and logistical problems engendered by moving a massive monolith for the sake of its public exhibition. Heizer’s project also inhabits the mass-mediated discursive spaces—which today involve a wider spectrum of media than those available in the 1960s—in which these processes become most visible.63 The massive expense and technological interventions that Heizer’s recent work has provoked compel us to consider how the magnetism of monoliths still mobilizes economic and aesthetic forces. Although Heizer’s geologically ancient monolith belongs to no p. 32 specific “ancient” or “primitive” culture, the bombastic spectacle of its movement was still successful in generating visibility not only for the artist who envisioned the project but for the institutions that funded and orchestrated the many stages of the process. Thus, Heizer’s work does more than just elevate the profiles of the cultural brokers behind such an onerous intervention; it invites us to reflect on precisely what makes these events interesting when no “higher” intellectual or exploratory quest is apparent in them. In remaining open-ended in this way, Levitated Mass reminds us that the carefully staged doublings of time are conspicuous spectacles of institutional might. But it also argues that these events should invite inquiry and contestation as they continue to happen around us.

Figure 12

p. 33