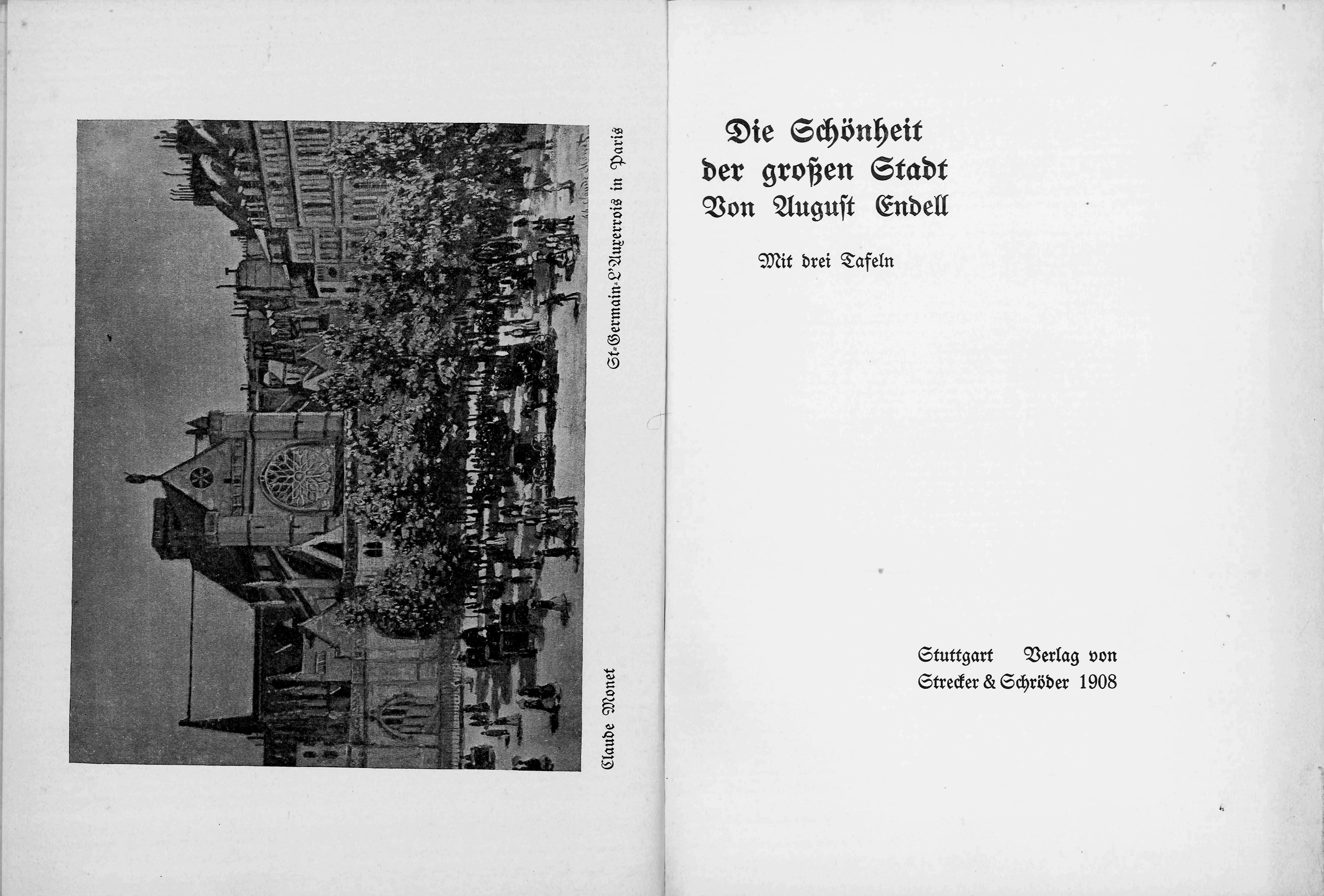

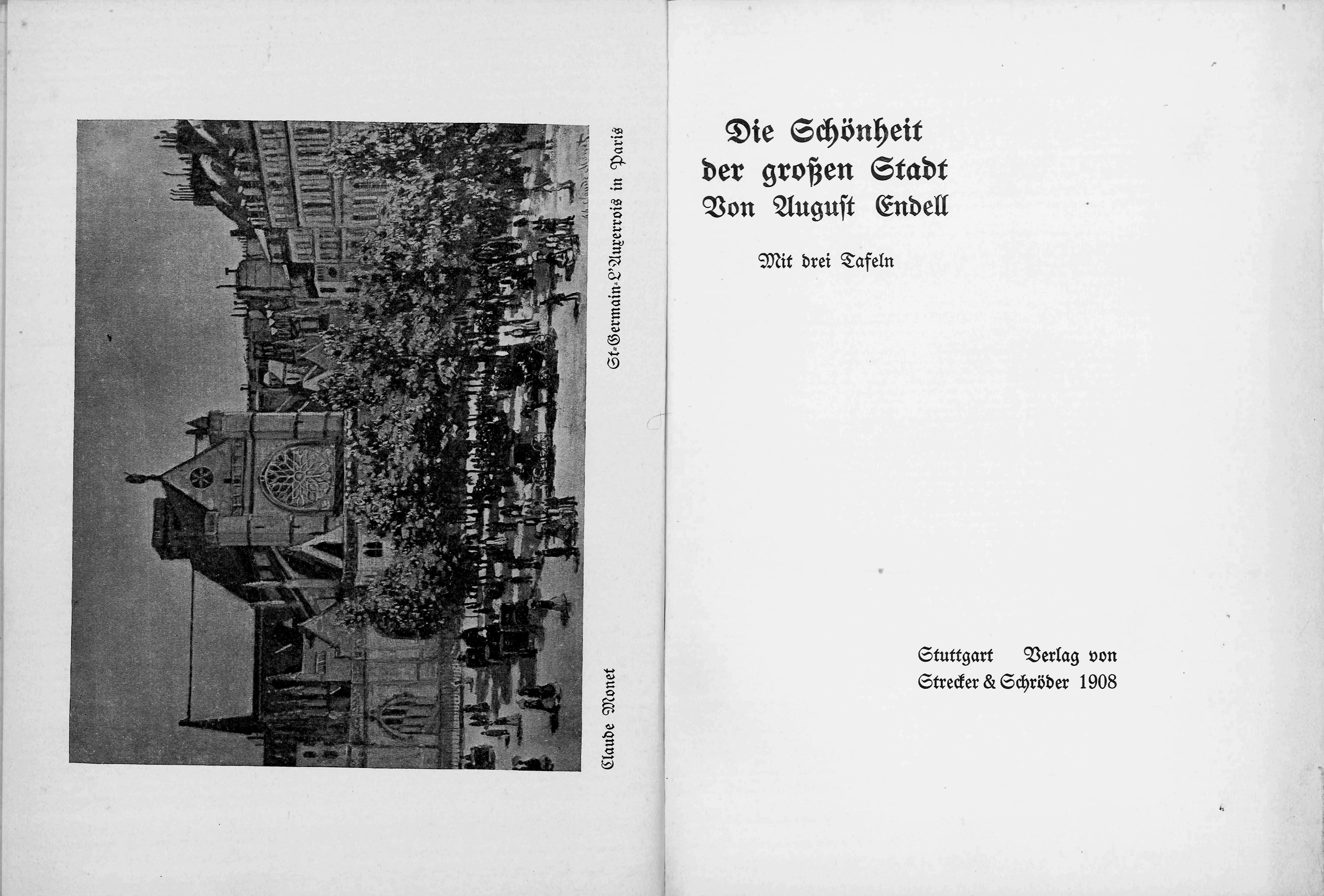

Figure 1 August Endell.

Die Schönheit der großen Stadt,

1908. Cover.

August Endell.

Die Schönheit der großen Stadt,

1908. Cover.

p. 116

August Endell (1871–1925) wrote *The Beauty of the Metropolis (Die Schönheit der großen Stadt) in 1908, a few years after he had moved from Munich to Berlin. Close to the artist Hermann Obrist (1862–1925) and the philosophy professor and empathy theorist Theodor Lipps (1851–1914) in Munich, Endell made a name for himself with the publication of his essay “Um die Schönheit” (On beauty, 1896) and the construction of his design for the Elvira Photography Studio in 1898. Once in Berlin he founded a private design school (Schule für Formkunst; School for Form-Art), continued working on small-scale architectural projects, and published countless theoretical essays. In 1918 he succeeded Hans Poelzig (1869–1906) as the director of Akademie für Kunst und Kunstgewerbe (Academy for Art and Applied Art) in Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland), where he taught architecture until his death in 1925.*

If the Elvira Photography Studio is the most familiar among Endell’s design work, *The Beauty of the Metropolis *remains his most important contribution to aesthetic theory. The text has two parts. The essay begins with a theoretical exposition, in which Endell condemns the contemporary impulse to flee from “the here and the now” to a dubiously pure nature and an imaginary past. The second part, published here, is a series of short descriptions of atmospheric effects from a city that is gradually revealed to be Berlin. Endell turns the early twentieth-century German antiurbanist literature on its head in this text by identifying beauties in a city notorius for its ugliness as well as its moral decadence and political unrest. Like Karl Scheffler (1869–1951) who found a fantastical element in Berlin’s formlessness, Endell proposes that Berlin, viewed from an impressionistic perspective, become a training ground for the modern sensorium. It is significant that in the midst of a public controversy about the acquisition of French paintings for public German museums, Endell made a point of illustrating the book with the work of Claude Monet and Max Liebermann.

The Beauty of the Metropolis should be read at the pace that Endell recommends that the modern beholder see the world. When seeing is slowed down so that the gaze is allowed to linger on every line, every plane, and every color, Endell claims, vision will acquire a novel sensuality. Furthermore, this newfound sensuality is synesthetic: light is not only a visual phenomenon in this p. 117 text but emits noise and produces tactile effects. Influenced as much by Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867) as by Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926) and Stefan George (1868–1933), Endell tried writing poetry early in his career. In The Beauty of the Metropolis*, Endell turns this poetry into prose: while sentences may occasionally lack verbs, they abound with adjectives and adverbs, listed with a relentless staccato rhythm that leaves the reader breathless at times. “Language is especially wealthy for the description of visible things,” Endell explains, but the question of language’s adequacy to describe a world imagined to be loaded with emotions—a question that remained a dividing line in psychological circles at the turn of the century—lurks in the background of* The Beauty of the Metropolis.Modern design, Endell suggests in the last sentence of the text, will be constructed upon the foundation of this new way of seeing the world.

—Zeynep Çelik Alexander

THE METROPOLIS

The Metropolis as the Symbol of Today’s Decline

The metropolis, the most visible and perhaps the most unique fruit of our contemporary life, the most conspicuous and complete form of our work and will, is predictably always the target of outrageous attacks. The metropolis appears to be the symbol and the most powerful expression of a culture turned away from the natural, the simple, and the naive; wild hedonism, nervous haste, and revolting degeneration accumulate into a greyish chaos in it, to the disgust of the virtuous. [The metropolis] corrupts the people that it deceitfully lures to itself; it unnerves them, and makes them weak, selfish, and wicked. The city dweller is disdained for having no home [Heimat]. The unspeakable ugliness of cities is condemned, their terrible noise, their dark courtyards, and their thick and gloomy air. It would be possible to ignore such Figure 2 August Endell. Die Schönheit der

großen Stadt, 1908. Title page

with frontispiece by Claude

Monet, Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois

in Paris, 1867. Painting purchased

by Hugo von Tschudi for the

Nationalgalerie in Berlin in 1906. p. 118 opinions, and many others too, if the city dweller himself did not want to believe in them, if he did not want to dream—under the name of Heimat—of low farmers’ cottages with windows shimmering at dusk, so familiar from the theater; if thousands of people would not pointlessly waste away their existence with such talk. It can certainly be considered a worthwhile goal to make cities disappear from the face of the earth. For the time being, however, cities exist and their existence is necessary if our entire economy is not to fall into ruin. Hundreds of thousands have to live in cities, and instead of implanting in people an unhealthy and hopeless longing, it would be smarter to teach them to see their city genuinely for once and to create out of their surroundings as much joy and vigor as is possible. It must be acknowledged, of course, that life in our cities is more exhausting, unhealthier than life in a small town or in the country. The objection can be raised that the city dweller is increasingly estranged from the soil, plants, and animals and thereby is robbed of many possibilities of happiness. It must be admitted that our buildings appear for the most part hopelessly boring, lifeless, and, at the same time, gaudy and pretentious. But the conclusion to be drawn from this is that we have a duty to change the way we build our cities accordingly, to build more spaciously, honestly, and artistically. And in need of even sooner fulfillment is the task of making up for the city’s faults by means of other enjoyments.

August Endell. Die Schönheit der

großen Stadt, 1908. Title page

with frontispiece by Claude

Monet, Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois

in Paris, 1867. Painting purchased

by Hugo von Tschudi for the

Nationalgalerie in Berlin in 1906. p. 118 opinions, and many others too, if the city dweller himself did not want to believe in them, if he did not want to dream—under the name of Heimat—of low farmers’ cottages with windows shimmering at dusk, so familiar from the theater; if thousands of people would not pointlessly waste away their existence with such talk. It can certainly be considered a worthwhile goal to make cities disappear from the face of the earth. For the time being, however, cities exist and their existence is necessary if our entire economy is not to fall into ruin. Hundreds of thousands have to live in cities, and instead of implanting in people an unhealthy and hopeless longing, it would be smarter to teach them to see their city genuinely for once and to create out of their surroundings as much joy and vigor as is possible. It must be acknowledged, of course, that life in our cities is more exhausting, unhealthier than life in a small town or in the country. The objection can be raised that the city dweller is increasingly estranged from the soil, plants, and animals and thereby is robbed of many possibilities of happiness. It must be admitted that our buildings appear for the most part hopelessly boring, lifeless, and, at the same time, gaudy and pretentious. But the conclusion to be drawn from this is that we have a duty to change the way we build our cities accordingly, to build more spaciously, honestly, and artistically. And in need of even sooner fulfillment is the task of making up for the city’s faults by means of other enjoyments.

The City: A Fairy Tale

For what is astonishing is that the metropolis, despite all its ugly buildings, despite its noise, despite everything that deserves criticism in it, is, for those who want to see, a wonder of beauty and poetry, a fairy tale more colorful and manifold than any tale told by a poet; a home [Heimat], a mother who everyday showers her children extravagantly with ever-new happiness. This may sound paradoxical; it may sound exaggerated. But he who is not blinded by prejudice, who understands how to dedicate himself, who busies himself attentively and insistently with the city, soon becomes aware that the metropolis embraces in its streets thousands of beauties, numerous wonders, an endless richness that lays exposed before everyone’s eyes and yet is barely noticed.

[… .]

THE BEAUTY OF THE CITY AS A LANDSCAPE

I intentionally leave aside the so-called natural beauties, which, contrary to what is claimed, the reviled cities are not completely devoid of: the public parks, mountains, rivers, and lakes. I will not touch upon the old architecture either: the pretty old houses, churches full of memories, and attractive squares from the past, although they too receive too little attention. Few know that evenp. 119 poor Berlin has enough of the arts of architecture [Baukunst] and city-building [Stadtkunst] that if one were to put all its old buildings and churches together, one could have a fine old (and not at all small) city. I will talk only about the modern city whose form, with ever fewer exceptions, is abominable. The buildings are flashy and yet dead; the streets and squares meagerly fulfill practical requirements; they monotonously stretch out without a break, without a lively feeling of space [Raumleben], without variety. One can wander the new parts of Berlin for hours and still have the feeling of not having moved beyond the same spot. Everything seems to be of the same shape despite the conspicuous struggle to stand out and to differentiate oneself from one’s neighbor. And even here, in these dreadful heaps of stone, lives beauty. Here, too, are nature and landscape. The changing weather, the sun, the rain, the fog make a strange beauty out of the bleak ugliness.

THE VEILS OF THE DAY

The Fog

The fog is perhaps the most vivid, but its beauty is barely noticed. It changes a street completely. It covers the buildings with a thin veil; grey, whenever the clouds above hide the sun; warm, golden, and colorful, whenever the sky above is free. It changes the colors of the buildings, makes them more unified and milder; it blurs the strong shadows, even elevates them, and these buildings, almost all of which suffer from a senselessly excessive amount of relief, appear finer, flatter, and more restrained. Even the cathedral, this dreadful product of handiwork that has lost its aim and rudder, appears as a wonderful image on this hazy fall day if the fog becomes visible and warm around ten o’clock in the morning; the pointless depressions, the thousandfold carvings and divisions disappear, filled up with the fog, and the disjointed forms become full and grand. The fog refines the terrible architecture, it fills the streets that otherwise seem to disappear into endlessness and renders out of the void an enclosed space [Raum].

The Air

While the fog palpably affects even the most inattentive eye, the air, which almost constantly wraps a thin, hazy veil over everything in our surroundings, has an effect that is gentler and less conspicuous. Its density changes, and so does this veil every day; sometimes it is almost unrecognizable, and then again it becomes more powerful in its effect. Beautiful, when the whole street seems to have been made out of a thousand shades of grey and black, with the colorful highlights of an advertising pillar or a yellow autumn tree. Beautiful, when, after a spell of dryness, everything appears light grey, almost white. Wonderful, when on bright summer days a gentle haze spreads a delicate, colorful veilp. 120 that is visible only in the shadows. Of course, as is the case in nature, not everything is beautiful. One must look for beauty. And that is more difficult, because [the metropolis] is unlike the natural landscape whose beauty has been painted or described a thousand times before. Often one will find tiny bits of beauty, as the reflective streetcar tracks in the grey asphalt or the recess of a balcony whose red wall, half-lit by the sun and half in shadow, contrasts with the grey wall of the house, producing a delightful play of colors. But often there are also large images that delight: a felicitous light, a beautiful distribution of shadow that falls across the street, creating an animated form out of boring regularity.

The Rain

The effect of the rain is entirely different. It does not blur the colors but makes them heavier, darker, more saturated. The light grey asphalt becomes a rich brown; the outlines become harder, the air becomes more visible, depths appear deeper; everything receives definiteness, massiveness. But above this the marvel of luster and reflections covers everything in a glittering web and creates out of the rationally functional street a shimmering fairy tale, a glittering dream.

The Twilight

Even wilder, more fantastic is the twilight. It compresses the haze of the day, deposits ever-darkening clouds in the depths of the buildings. The streets appear to be filled in at the bottom right and left; all forms appear quieter and heavier; all colors duller and milder; everything darkens gradually, only a few points glow, the colors of a car or of posters on an advertising column that seemed so glaring during the day sound pale and delicate in the sinking grey. But the sky drowns out everything with its light; it dazzles the eye and spreads over the whole street a mantle of flickering, uncertain, quivering light that is everywhere and yet comes from nowhere. And then suddenly the sunset flashes; everything that seemed grey and dying before glows with warmth. The whole air is filled with warm, bright colors; all colors become vivid; the tops of the houses and churches glow in bright yellow-red; and the radiant blue of the evening spreads itself in the dusky streets. It penetrates everywhere; it is stronger than any artificial light; the narrowest streets are filled—perhaps it is strongest there. It is an unforgettable experience [Erlebnis] to sit around this time in a café on the first floor and to look down on the ever-darkening masses of people, to feel suddenly the flaring up of a little piece of sky above, and then to see how the blue tide fills entire streets, how it penetrates through large windows into smoke-filled rooms and how in a moment it displaces the newspaper, the cards and the conversations, and all the triviali-p. 121 ties of banal experience.

The Veils of the Day

Fog, mist, sun, rain, and twilight: these are the powers that clad the great stone nests in an endless cycle with an ever-changing brilliance of colors; their forms coalesce, making them sometimes more self-enclosed, sometimes monumental; they build out of the poorest courtyards and out of the most desolate quarters a world of more colorful wonder. They fashion out of the seemingly immutable heaps of stones a lively entity that perpetually forms itself [sich gestalten]. An individual could never exhaust all the wealth; experiencing what is offered by his surroundings, his yard, his house, the streets that he walks everyday, is in itself a full occupation.

The Gabled Wall

In front of the window of my study stands a tall gabled wall. From my desk I can see nothing except this wall and, if I go right up to the window and bend back my head, the sky. The wall is unplastered, made from bad bricks, sometimes yellow, sometimes reddish, with grey, irregular joints. But this wall lives; it is a different creature under different weather conditions: it is grey, drab, heavy on cloudy days, becomes animated on bright days. Then the red brick gleams stronger than usual, and the irregularities of the wall stand out more clearly and give it a glistening texture. Sometimes the sun shines on the wall’s upper part. Then the wall above becomes fiery and glazing and the part below takes on a soft, delicate, blue tone. Against the wall (I live on the second floor) stretch the tops of some trees with thin, glossy branches from the so-called garden; in the summer the tree has gigantic leaves—the tree wants to live and the top leaves are the first to drink in the powers of the sky—and their heavy green is rich and full against the dull tones of the wall. But in the autumn when the leaves start turning yellow, the wall irradiates; illuminated and shaded by the sun, a soft light emanates from it, making the shades appear cool and bluish. And when other leaves turn red, then a picture of wonderful delicacy emerges: the red of the leaves glow in front of the delicate red of the stone. But when one looks at the garden in the late afternoon, if a gentle fog envelops the trees, then one finds himself in a magical land: in the darkening space in front of the purple shimmering wall float the colorfully glowing leaves, and around them undulates the twilight, appearing, disappearing, turning blue. Then comes the winter, the leaves fall, and one day in front of the reddish and bluish glowing wall emerges the top of the tallest tree, alone struck by the sun, ghostlike, incomprehensible, like a golden whisk.

p. 122

The Street

And just as this wall reflects the life of the year, so does the street in front of my house. I go down every morning for a few moments to see how it changes. Its length changes constantly, depending on the visibility of the air; the ends are almost always closed by the haze and, depending on the sun and the shade, the buildings seem higher or lower; they move closer or farther away. The grey of the footpath and the embankment, the green clouds of the rows of trees, the black columns of the trunks, they appear different every day, not always beautiful, but often so delightful that I cannot tear myself away. And so it is everywhere.

The Romanesque Church

Nearby stands a Romanesque church. Dreadful, most dreadful as architecture, confused in its composition, absurd in its proportions, misguided in its details, laboriously assembled out of a thousand tired precious details. Architectonically speaking, the view is the most horrible thing I can think of. It is impossible to get used to it. And yet I look every day at its towers. For the air and the haze make a new wonder out of the church every day. The stone roofs of the towers, made darker than the walls and the gables by the rain and the weather, dominate all the streets around, and every day I see them in the changing light of day. Sometimes they appear to be pale grey and far away in the background of the grey sky. Sometimes they are almost dark and menacingly close; they appear green after the rain, and from certain sides even purple; and then when illuminated by the blue sky, they are almost white. They are different when seen from a distance, different when seen closer up, different in the light, different in the shade, different every hour and every day, and they too are only a piece of the living essence [Wesen] that mysteriously and powerfully always surrounds us and that we know how to describe only with paltry words such as weather or climate.

The Iron Bridge

As one notices changes in what is seen every day, the loveliness and scale of streets and neighborhoods rarely experienced are engraved upon one’s mind. Among the most powerful sights that I know is an iron bridge of the Stettiner line. Behind the railway station is a street that stretches along the embankment, on the right a row of five-story buildings without balconies, flat, dull, formless. But in the distance rises a dark monster. For there the railway turns a little to the right and crosses the street overhead with its seventy-meter-long bridge. The road dips there under the bridge so that it looks as if the bridge almost touches the ground, the gigantic load-bearing walls shift against each other and form a dark, leaping mass that skirts the last building and seems top. 123 rush toward it. The black, towering, moving mountain seems like a trumpet blast; the heart stands still when beholding the immense force, passion, and size of the hulking mass. I could compare it to only one thing. It was in the port of Kiel. The armored cruisers were widely spaced from each other a fair distance out. And among them was one that had its signal flags hung out for drying: that was the same passionate, terrible roaring, perhaps even more intense because of the wild colors that faded into a shrill red: the whole thing a huge, blood-red crest wafting heavily from the deck to the mast in tremendous contrast to the giant forms of the ships in their silent grey.

Geleisdreieck

Similarly enormous, but more disrupted are the great arches of the triangular junction of the elevated railway, a strange contrast to the thin, obscure forms of iron construction.

The Schlesische Train Station

Quite different, glistening, almost playful but also overwhelming is the hall of Schlesische Station, the colossal roof area of 207 × 54 meters, held by countless thread-thin iron rods, so thin that one can barely follow their coherency, that the eye almost perceives it as the sensation of painful cutting. An abhorrent architectural effect, but unparalleled when a fine mist fills the vast hall and the iron bars seem like an endless, glittering spider web.

The Street of Birdcages

In strange contrast, the sight of certain streets in the northeast of the city in midsummer. The buildings are very tall, taller than what is now allowed, but without any bay windows, hideously plastered with a thousand misguided, lifeless forms. Two tall, dismal walls: the senseless profusion of moldings and profiles spreads a web of black shadows where the sun hits the surfaces, and makes the dull grey of the paint even heavier on the shady side. But all these buildings have on each floor two latticed balconies that look like small birdcages, and each cage is completely full of the dark green and red of the flowers and the vines carefully cultivated there. So the walls of the street seem to be covered with thick, richly colored nests, which, in perspectival foreshortening, look like they are all right next to each other, giving the cheerless, meager street a curious attractiveness of subdued passionate fervor, of fantastic grandeur. Thus, a picture of rare beauty can emerge out of a schematized paragraph of the building code, out of the ruthless exploitation of land, out of the lack of architectural judgment, and out of the longing of the imprisoned dwellers of the metropolis for flowers and growth. Of course, this is an especially happy coincidence.

p. 124

It is easier to have grand impressions where the scale of the engineering structures already has a certain degree of monumentality in raw form, especially in the great hall of factories, whose beauty is admittedly known to only a few, and, above all, in the halls of train stations.

Friedrichstraße

Train Station It is wonderful when one stands overlooking the Spree on the outside platform of the Friedrichstraße train station where one sees nothing of “architecture” but has in one’s field of vision only the giant face of the glass curtain [Glasschürze] and the contrast to the petty chaos of buildings all around.1 It is especially beautiful when the twilight with its shadows fuses together the tattered confusion of the surroundings into a whole and begins to reflect the many small slices of the red sunset, when surfaces acquire colorful, shimmering life, spanning over the deep, dark, nocturnal chasm out of which the squat bodies of locomotives push forward threateningly. And then what a climax when one goes into the darkening hall, still filled with uncertain light: the gigantic, slowly curving form vague in the dim haze, a sea of grey, soft color tones, from the brightness of the rising steam to the heavy darkness of the roof and the full blackness of roaring locomotives, coming in from the east; above them the evening sun shines brightly on the dreary surfaces of the glass curtain like a towering, shimmering, red mountain, like some roof gable kindled by the evening sun to a glaring fire.

VEILS OF THE NIGHT

If the day has a thousand colorful veils, the night in the city has even more. Starry skies and moonlight hardly ever show to advantage, but the artificial lights bring about infinite plays of color. Already in twilight their presence is felt. It looks lovely when the long rows of green street lamps emerge in the blue glistening street, under the glimmering pink sky in fine chiaroscuro, all colors sound muffled: first barely visible, then as colored dots, and only then with their own lives in the falling darkness. Slowly the night fills the streets, like a vessel higher than the street walls, densest at the foot of the buildings. The glare of the deep blue sky helps to increase the veils of the shadows, and in this sea of mist and layers of shadow the colorful lights begin their eternal game. Their colors and intensities are very different. The green and yellow white of gas lights, the mild blue of the ordinary arc lamps, the red and orange colors of the Bremerlicht, and the new varieties of the arc lamp, the red and white of the lightbulbs and metal filament lamps.2 In addition, the dark red and green of signal lights. Every street offers new arrangements and contrasts.

The Hardenbergstraße

Wonderfully quiet and big, a wide street, like the Hardenbergstraße, illuminated with only two rows of bluish arc lamps, the whole street in clear, full light, without being interrupted by the clamor of store lights. The buildings to the right and left appear to fall back in the twilight, and the trees in the front yards assume a strange appearance different from their appearance during the day; they almost resemble mountains of moss upon which lightgreen tips also stand out from a deep-black background. Dark-green clouds are nested ghostlike in the depths of gardens, but wherever the thick branches of trees extend over footpaths, there the jagged forms of leaves light up brightly, making the light falling through them appear to those underneath as if surrounded by an edge of flowing light, the whole thing a gleaming lace veil, delightfully beautiful in its dainty sharpness, in its rich density and movement. And on the ground against the cold gleam of stones is silhouetted the fantastical web of leaf shadows in subtle, warm tones. On rainy days, however, the picture changes completely: the street turns dark, the light grey smoothness of the asphalt becomes brown like milky coffee; the waves of its surface glitteringly reflect the light of the lanterns. The air is filled with fine, fresh mist, and the whole sky seems covered with a wonderful veil of bluish purple.

The Shopping Street

The light is very different in the narrow streets, where rows of buildings, pushed closer together, make darkness more palpable, where rows of trees wrap the upper floors in shimmering shadows, which to the dazzled eye appear to be dressed with delicate light. Bare and bright lies the dry asphalt without reflection, only the tram rails gleam, but under the trees, beyond the reach of the lights hanging in the middle of the street, a thick, colorful light breaks out in great mass from the lower floors of the buildings and from long rows of shops so that human figures have the effect of black shadows. The buildings appear to float in the air, and among them, as if from unlocked mouths, flows a tide of shining light.

A Side Street

A quiet side street, by contrast, makes a dark impression. If [on the shopping street] there seemed to be a corridor of light along the buildings, here the street is filled entirely with darkness, and the few gas lamps burn in small cages as if burrowing in the air. The gas lamps have an uncertain halo of light around them, but they illuminate hardly a few meters; furthermore they act only as points of light, while the strong light sources carve in the air huge vaults filled entirely with light. And if we enter into this vault of light, then we are surrounded by rings of light; it is as if we are inp. 126 a space that has around it a transparent but distinctly perceptible wall. It is particularly delightful when one sees from such a space of light the distant lights of another such space as if through a veil. This I felt once very strongly, on Schloßstraße in Dresden.

Schloßstraße in Dresden

Many red-burning arc lamps fill the narrow street there; they drill themselves a vault that reaches up to the third floor and forward to the Old Market. But the market shimmers in blue lights, and this can be seen only faintly through reddish walls that surround one like gentle music. Of course, this depends on the atmosphere. In stifling, dusty nights, the cavities are smaller; after rain and wind they often grow to surprisingly gigantic proportions, indeed almost seem to disappear. It is also very pretty when faint lights acquire importance by throwing cones of light onto high walls, thereby creating large color fields. This is also the case with the above-mentioned Romanesque church, which has arc lights on bordering streets and gaslights only on the square. And now the bright limestone shimmers in a soft, dull green, and the whole church seems to be encased by a dark cloak and separated by busy roads while the towers become invisible in the low-hanging night.

On the Canal

Yet other effects emerge in the dimly lit canal lined with two quays, each of which is planted high with three tall rows of trees. The dense tree crowns prevent the dispersion of the light completely. The silent buildings rise darkly behind the shadowcasting clouds of the canopies. The gas lamps have the effect of points of light, which are joined by the wandering carriages and automobiles: a subtle, blinking web of stars spreads over the dark masses. The sluggishly flowing, smooth water is all black, and the ghostly silent mirror image of quiet nocturnal life shimmers from below to the pedestrians above. And it is lovely when, making one’s way around a bend, one is confronted suddenly with the fanfare of the brightly illuminated Potsdamer bridge with its tremendous life.

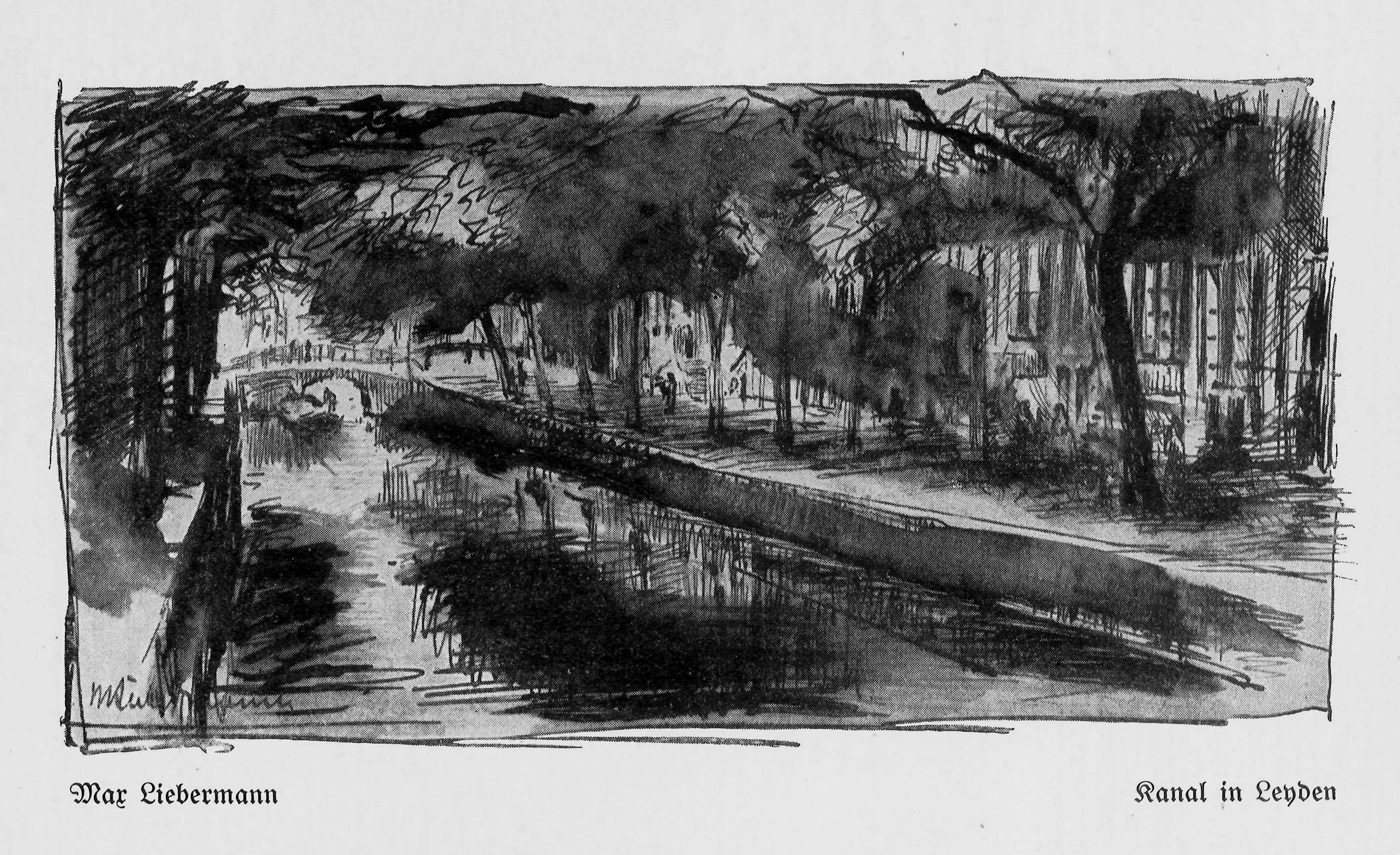

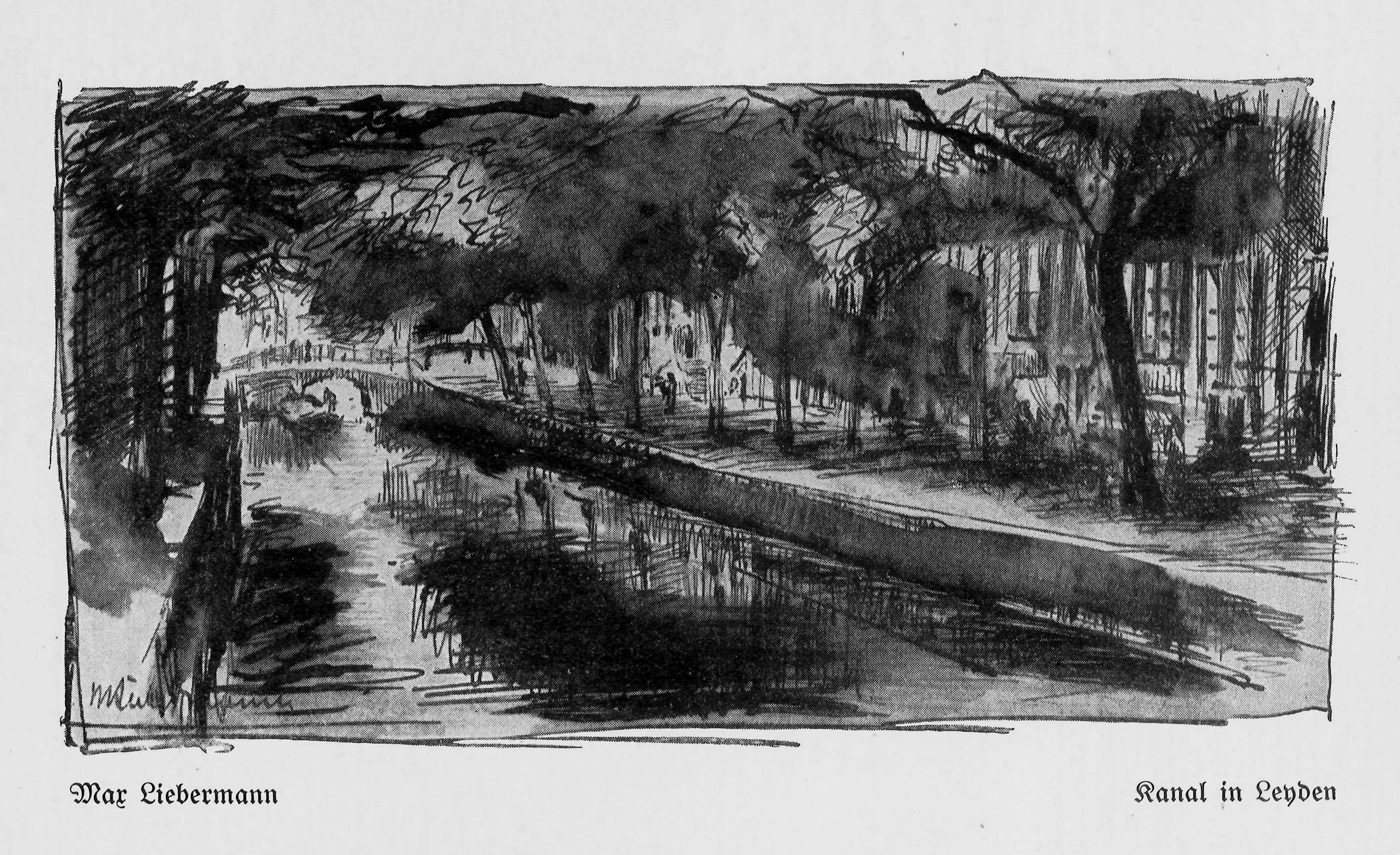

Figure 3 Max Liebermann. Canal in Leiden,

ca. 1900. From August Endell, Die

Schönheit der großen Stadt, 1908.

Max Liebermann. Canal in Leiden,

ca. 1900. From August Endell, Die

Schönheit der großen Stadt, 1908.

p. 127

THE STREET AS A LIVING ESSENCE

If the veils of the air, twilight, and artificial light create out of the dumb waste of streets strangely fantastical shapes and forms, to which their builders had not given any thought, and if out of soberly cubic rectilinearity emerge sleek, animated, generous forms with the aid of shadow and shimmer, so emerges out of people and traffic an element that creates a living entity out of silent forms, an element that awakens and acts and becomes exhausted, that is one way on most days and another on festive days.

People as Nature

In general, human beings are not considered as nature, quite the contrary. The modern moralist (he usually does not belong to a church) is only too willing to view human beings as evil from youth onward, as the source of everything unnatural and detestable. For that reason, the philistine—who has neither the knowledge to understand suffering and mistakes foreign to him nor the inner happiness that makes one strong enough for compassion— fearfully avoids the mob and only shouts out his curse from a distance, from a secure corner. And yet it is in the metropolis that one can get to know people from a perspective that is endlessly appealing, a perspective that inevitably remains hidden in smaller communities. In the latter, everyone knows everyone else; the other is a seeking, demanding person. One must talk when one meets the other, must greet, must establish some kind of a relationship. In the metropolis one passes everyday by hundreds and thousands, keeping silent like a stranger, as if passing by trees in a forest. The people are only appearances, they are organizations for themselves, organizations whose inner coherency does not affect us, but whose gestalt is accessible to us like the forms of mountains and trees. Human beings as part of nature. And this part of nature is just as charming and attractive as any other. What an abundance of types, of variation in age, in development, in the shape of the body and the soul. Only for the fool and the ignorant are the exterior and interior separated. For those who know how to see, gait and posture, eye and mouth are indications of inner life, but not tediously, in the form of endless external occurrences that so actively provoke the curious, but rather in a manner that unites life, in a manner that brings together its unique pace, warmth, tension, complexity, refinement, momentum, and strength and makes it immediately available to feeling. Few things are nicer than sitting in silence in the tram and watching strangers, not in order to eavesdrop on them surreptitiously, but rather in order to experience in an observing, feeling way, to enjoy. How much beauty can be found in old age, in sickness, in sorrow, in severe pain; it is often quite gentle, imperceptible, hidden from the inattentive but overwhelmingp. 128 even the blindest with magnificient loudness. It is strange to think that all sense of beauty originates from sensuality. That is putting things topsy-turvy. Sensuality awakens the eye, but the more subtly one sees, the more delight one derives from forms that would have never triggered one’s sensuality. And that is why some doctors do not want to understand that artists can represent sick people for their beauty. How subtle the sick colors of children of the metropolis often are, how their features sometimes take on a wonderful, austere beauty precisely because of hardship and privation. And even depravity and impudence may have beauty, strength, and indeed grandeur. The naive person sees beauty only where he desires. The person who sees truly, though, knows how to recognize beauty even where his desire does not speak to him. That is why he is able to sustain unfeigned interest, to enjoy and to give, whereas the “healthy” and the “unspoilt” run away in terror and cry out aloud to vent their indignation. The world would indeed be intolerable without the beauty of weakness, old age, and illness, and he who knows how to find [beauty], will be able to walk in the poorest parts of the city without fear.

Women’s Clothing

It is certainly more lighthearted to stroll in the streets of wealthy neighborhoods to watch the colorful throng of women. The much-maligned women’s fashion is indeed almost the only form [Gestaltung] that is alive and well today. The pedants who consider fashion foolish and pointless because of its ephemerality sin against life. For fashion is but a symbol for life itself, which is always passing, changing, which pours out its gifts lavishly without calculating anxiously whether the expenditure has a reasonable relation to gain. Nature scatters thousands of seeds all over, even if only one should bear fruit; and it is this extravagance of thought, this eternal start, this colorful richness that makes fashion so enjoyable. Doctors rightfully disapprove of the lacing up of the body [with corsets], and anyone who knows naked beauty will agree with them. Not much will change before pools in the open air and bathing together reveal the beauty of the nude and make it desirable again. Until then, however, reformers will have to make other expenditures of taste and sentiment in order to confront conventional fashion in a serious manner. [Conventional fashion] is still far superior in terms of sense of color, elegance, charm, and casualness. Here, too, the sense of color—the only thing that we have acquired from the culture of the eye in recent years—asserts itself pleasantly. And instead of morosely reprimanding failures, we should recognize how much more attractive materials have become, how much subtler their tonality, how much more our day has developed the ability to put together colors, arrange them, and fine-tune them. Even ifp. 129 lace and embroidery (and detail in general) leave much to be desired, the whole is often sufficiently attractive or at least more successful than most of what is vaunted as the great achievements of the “modern room.”3 The latter means something only in terms of color. Its formal poverty and crudeness are naturally more visible and more embarrassing compared to a dress, which lends the movements of the wearer an allure without which details are erased and forgotten.

Man and Street

Even if one did not accept [fashion’s] beauty, there would still be the beauty produced by people lingering in the streets, entirely independent of individuals. One person, one moving point, is already enough to change the impression of an orderly symmetrical street. [The street] receives, as it were, an asymmetrical human axis; the free space is divided by the moving body; distance and scale receive new meaning. When a human figure rises out of the flatness of a street, the spot receives a particular emphasis in perspective, it becomes clearer in its spatial arrangement, and because the human figure is of a certain familiar average size, the space is perceived immediately as a result. The flat image of the eye, which registers only subtle shifts of depth, extends back.4Man creates through his gestalt what the architect and the painter call space [Raum], which is very different from what is meant by space in mathematics or epistemology. The painterly architectonic space is music, it is rhythm, because it confronts our self-expansion in a particular way, because it sets us free in exchange, it surrounds us. The street as an architectural space is still a miserable product today. Air and light make it better, but it is the people moving in it that apportion it anew, animate it, widen it, fill the dead street with the music of the rhythmically changing space-life [Raumleben]. What is more, because people walk the same street in different ways—different in the morning when rushing to work, different again when women go shopping, different before noon, different in the evening—the streets are divided into the silent, the loud, those hastily trodden upon, and those strolled upon by people taking in the sights. Streets acquire their hour of life; they have good sides and bad; there are Sunday streets and there are everyday streets, all clearly separated by density, haste, and the kind of tumult that today appears grey and hurried, on another day colorful and easy.

Horses and Vehicles

And the mass of horses and vehicles. Here too in beautiful individual forms, a trotter, an English riding horse, or the heavy working horses with thick shanks. The vehicles [on the street] only rarely have that fiercely sleek beauty that we admire in mod-p. 130 ern sailboats, the impeccable lines, impeccable materials, and impeccable detailing. Carriages modestly boring, automobiles still uncertain in their form, carts often wonderfully colorful and bizarre. They should not be considered in detail, not as matter-offact form [sachliche Form], but they make attractive and pretty pictures, where foreshortening creates strange new structures, where the bright paint finishes appear softer in the veils that cover everything. Especially in the twilight, this coming together and apart of clusters of forms becomes noticeable; the evening’s clouds of shadows fill out the forms. Horse and cab become one; they appear to the living eye as a grey mass with dark shadows and sparkling highlights here and there. The perspective seems to disappear completely; there is no longer foreground and background; the whole resembles a walking nocturnal mountain over which the red, dim lights of the lanterns light up ghostlike. And so all the vehicles become wondrous living things: the gigantic yellow boxes of the postal stagecoaches, the shaking, thunderous cabs of the omnibuses, and the glass vessels of the trams that seem to glide along with their shiny green bodies, pushing themselves around curves in a surprising manner and projecting flashing lights as they turn around bends.

Altogether [the vehicles] create the space of the street and contribute to its hour of life. They stretch up and down the streets, fill the space between the sidewalks, throng, threaten the dense swarms of traffic arteries, trail off, sink into quieter streets. But wherever they come, they bring movement and liveliness. Even when they stand still waiting, they give the street a new and unusual appearance that always subtly changes the sense of space. Wonderfully beautiful images often result. I remember very vividly one such view.

Under the Iron Bridge

It was in the heat of the summer somewhere up in the north on the circular railway system [Ringbahn] where the rails on the bridges, instead of being carefully bedded on sand out of consideration for the neighbors’ ears, were laid hard and rattling on the construction site. Under such a bridge stood a cart with wooden beams, pulled by two heavy horses whose powerful heads sank in exhaustion. They stood on the side of the road in front of a yellow brick wall and the opening of the underpass appeared larger and wider as a result of their standing there. On the other side were two children whose presence made the space more tangible. Outside, the sun loomed in a stifling haze and the brightness seemed to enclose the space forward and backward with a transparent cloak, and bluish shadows seemed to fill the void. But a thousand scattered rays of sunlight rippled through the gaps of the iron construction, as if through tree branches, into the shadyp. 131 coolness, spreading over the dusty street, over the children, over the yellow wood, and the silent, gigantic horses.

The Life of Space

It is the life of the space [Raum] that gives here, as in all similar situations, such a strong and meaningful basis to form and color. It is difficult to convey a clear picture of this. It is customary to understand under the term architecture the elements of a building, the façades, the columns, and the ornaments. And yet all of this is only secondary. What is in fact most powerful is not form but rather its reversal, the emptiness that spreads out rhythmically between walls, that is defined by them, but whose liveliness is more important than the walls themselves. Whoever can feel space, its directions, its scale; whoever understands that the movement of the emptiness means music; to him is granted entrance to a nearly unknown world, the world of architects and the world of painters. For just as the architect derives pleasure from the play of space-movement [Raumbewegung] between the walls that are his creation, similarly gratified is the painter who forms intricate, manifold space in the landscape between mountain and forest and in the city on the ground of the streets between people and cars.

In Front of a Café

In this regard, among the most astonishing is the life of a square. Across from the ill-fated Romanesque church is a café with a terrace where I have often sat for hours on summer evenings, and where I never grow tired of watching the colorful play of people’s comings and goings. The square is misguided as architecture, perhaps even worse as a traffic system—as if someone tried to produce the greatest possible number of dangerous crossings— but it is unique as a field over which human figures are distributed. The crowds of the neighboring streets dissolve here in all directions, and the whole place seems covered with individuals. The people move apart from each other. Space stretches between them. With a shifting perspective, the more distant figures seem increasingly smaller, and one clearly feels the vast expansion of the square. All of the people are free from one another; now they move toward one another in dense groupings; now there are gaps; the formation of the space is always changing. Pedestrians push themselves through, conceal one another, detach themselves again and walk freely and alone, each emphasizing, articulating his share of space. The space between them thus becomes a palpable, immense, living entity. What is even more extraordinary is when the sun endows each pedestrian with an accompanying shadow or when the rain spreads a glistening, uncertain reflection underfoot. And in this strange space-life unfolds the swarmp. 132 of brightly painted trucks, the colorful dresses, everything united, cloaked, embellished with the veils of day and of dusk.

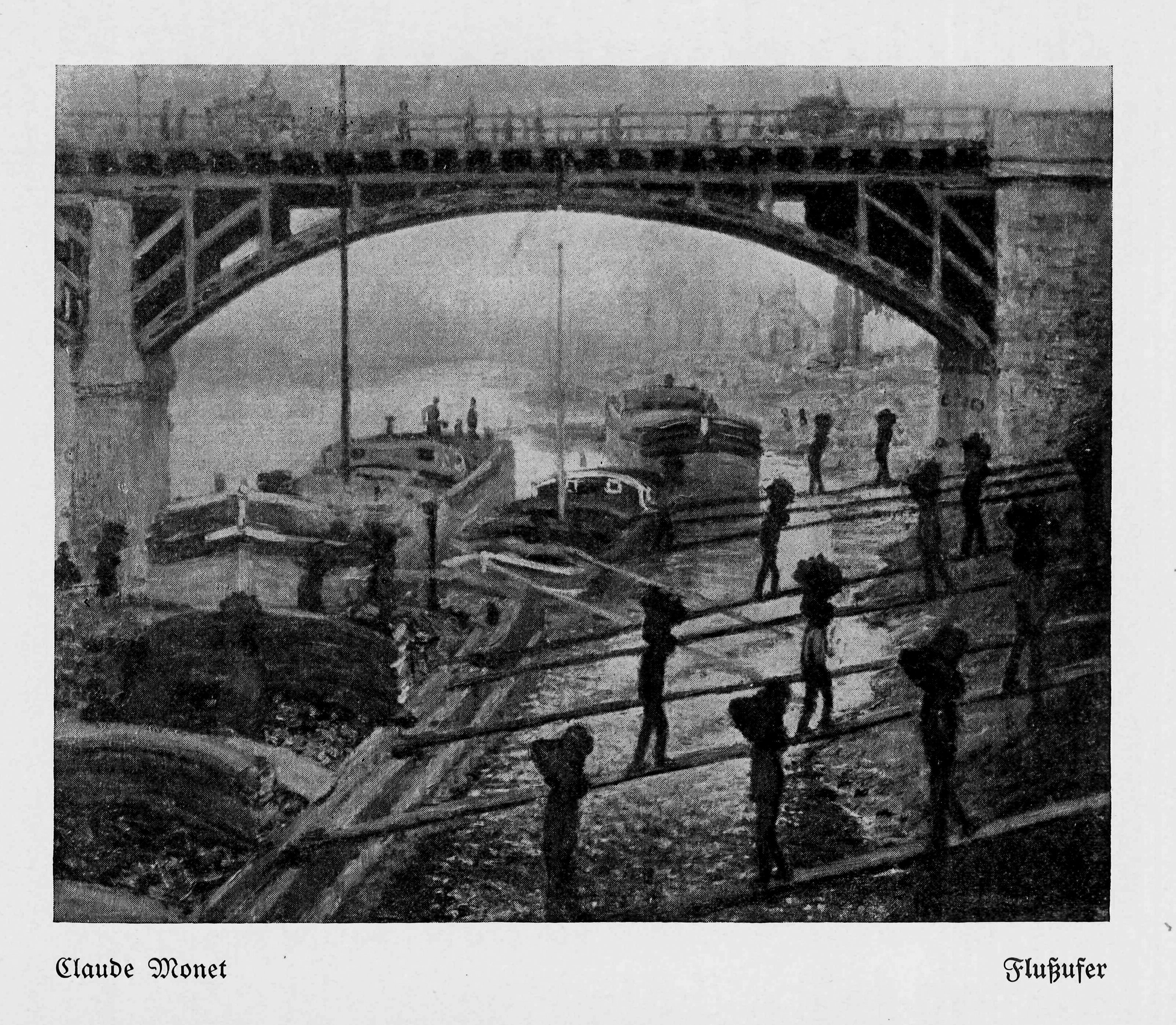

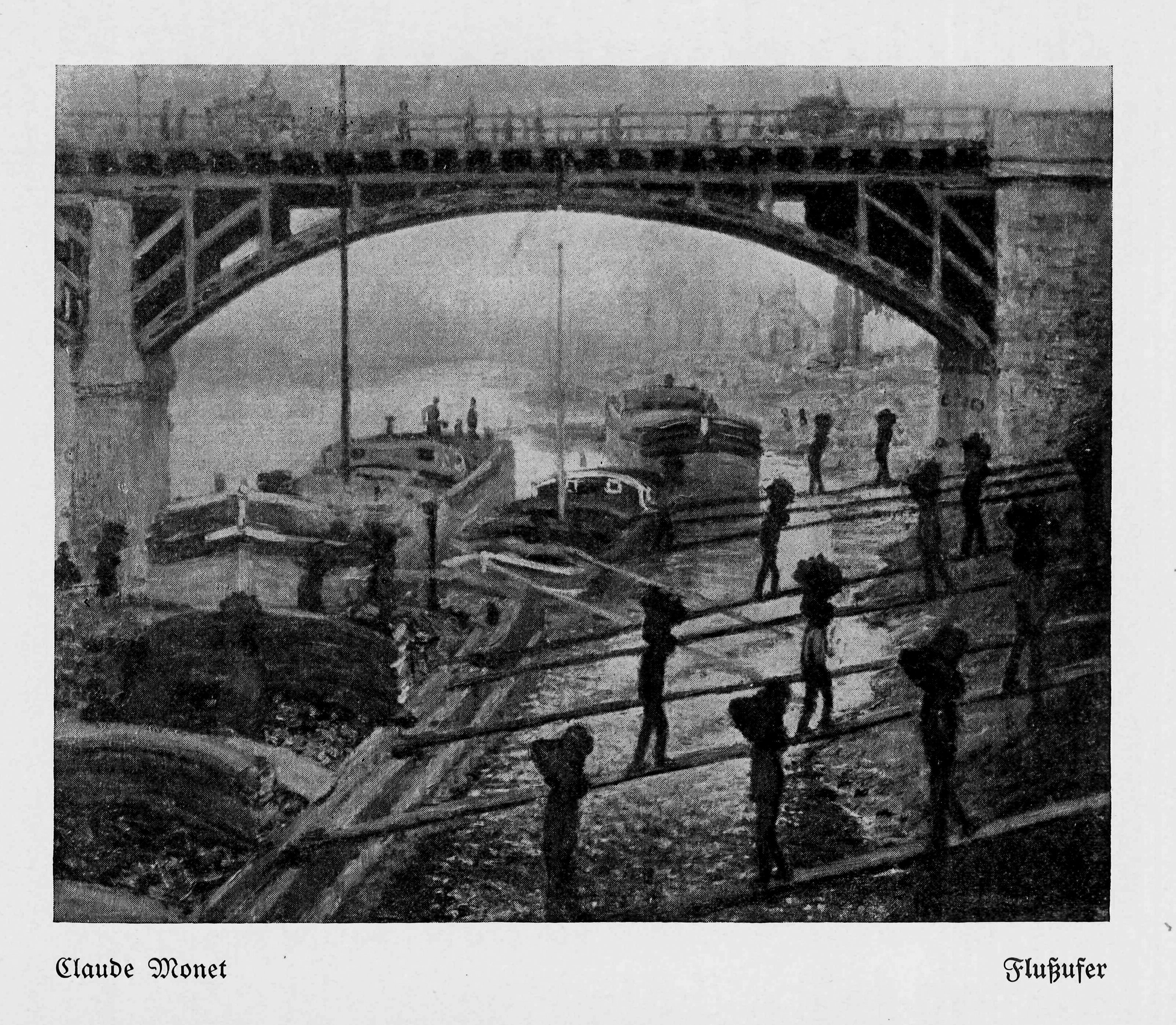

These things have almost never been painted; in pictures masses of human beings almost always fuse into formless lumps, with some free space between them, but this is not living space. To achieve this, the tones of the atmosphere would have to be seen more subtly and keenly than usual. I recollect a Monet painting that reflects the peculiarity of phenomena. On a riverbank is a large barge, parallel to it are multiple planks that reach the land, and workers carrying loads walk upon them. Occlusion, perspectival distortion, the recession of figures, and their standing independently of one another, everything shows to wonderful advantage.

Workers in a Structure

Similarly, I once saw a structure in a great hall, with unfinished walls and exposed steel beams, its windows boarded up to hold the cold at bay, so that semi-darkness spread on the floor, which consisted of rhythmically arranged iron bars. Then came a crew of workers, walking slowly and heavily over a path formed by the planks, each carrying on his back a heavy brown sack of concrete, and this slow-moving line gave the desolate, tall space an incomprehensible ceremoniousness. For a few moments, this made me forget everything around me, including my work, my reason for going there.

I ask you not to think of [Constantin] Meunier here. It was not the sublimity of work—or whatever the stilted phrase might be— that made the picture so great. Like many others, Meunier brought grandeur to the worker; he glorified him, made him Greek, because he did not see the worker’s true beauty. These workers did not walk with strained muscles, with which an actor postures effort and strength; instead they walked bearing weight cautiously with the knowledge of experienced people who understand Figure 4 Claude Monet.Les charbonniers,

also called Les déchargeurs de

charbon (The Coalmen, also

called Men Unloading Coal),

1875. From August Endell, Die

Schönheit der großen Stadt, 1908. that it is a while until the end of the day and that even the strongest must save his strength to make it last. And precisely this slow, peculiar motion, of which we know nothing in the theater, had beauty and charm; it filled the room with a solemnity that was all the more immense because it had never been seen or felt in that manner before. I dwell on this point at length because I want to eliminate misunderstanding, and because I have never read anything about it.

Claude Monet.Les charbonniers,

also called Les déchargeurs de

charbon (The Coalmen, also

called Men Unloading Coal),

1875. From August Endell, Die

Schönheit der großen Stadt, 1908. that it is a while until the end of the day and that even the strongest must save his strength to make it last. And precisely this slow, peculiar motion, of which we know nothing in the theater, had beauty and charm; it filled the room with a solemnity that was all the more immense because it had never been seen or felt in that manner before. I dwell on this point at length because I want to eliminate misunderstanding, and because I have never read anything about it.

p. 133

It is these effects of space and movement, joined by the veils of the atmosphere and light, that create an unfathomably colorful fairy-tale out of the metropolis, a tale that can never be exhausted. I want to pick out a few pictures from the wealth that I experienced in recent years, pictures that can perhaps give some idea of the magnificence of these things.

Parade Ground

In Westend there is a parade ground that stretches out. A deep cut of the railway borders it to the south, villas located snugly in gardens to the north, and tenement housing to the east—the building “development” of this section is underway as well—and the edge of Grunewald, just on the other side of another incision of the railway, draws the boundary to the west with a low forest edge. On cheerful Sunday afternoons the vast field is covered with people; throngs of pedestrians pour down from the bridges, from the adjacent streets they come in dense crowds, but the wide field entices them, as it were. The masses dissolve, scatter themselves, a colorful back-and-forth emerges. Multiple football games are carried out simultaneously. The large playing fields, marked with flags and enlivened by the colorful specks of the players, seem tiny in the vast plain. The vast number of viewers does not suffice to form fixed lines. Everything is free, free to stretch into infinity. A triumphant feeling of happiness spreads through the people. The individual with his suffering and struggles of life disappears; collective life is clearly palpable; it acquires a visible form [Gestaltung]. It is wonderful to go through the crowds, not thinking but rather feeling the people. But this is not the strangest thing. Most curious of all, powerful, mysterious, and unchangeable like destiny, is the ground that carries this crowd. It is light green with large brown spots that recede in perspective and become smaller in the distance, making the width of the expanse more pronounced. And this ground is gentle and undulating; so is the large carpet of people covering it. They play, walk, stroll, in this direction and that: without knowing they make a wonderfully immense form, a form borrowed from the ground and yet stronger and more formidable than the bare ground; colorful, richly animated, intersecting with itself a thousand times, but in its movement unconditionally accepting a secret law, the law of the ground. Of course, I mean this without any obvious literary symbols. As our eyes take in [this picture], it is not the resemblance but the thing itself that makes this picture so incomparably powerful. And this is proof that our eyes can experience things directly [direkt erleben], and not only intellectually or poetically as is usually assumed. It is also marvelous when the evening twilight brings a quiet order to the tumultuous masses as everyone rushes to the bridges leading into the city to go home.

p. 134

Unter den Linden

The colorful crowd is like a forest, and for those who stay still, who can see and surrender themselves, it is as refreshing and wonderful. I sometimes go into the city on hot Sundays, when the well-off flee Berlin, when the stifling haze and the stagnant hot air make it unbearable to stay in my room. I go under the linden trees in order to see the great parade of people dressed up, heading home. Then the beautiful forum of Frederick the Great is almost empty of cars, and the giant bright asphalt surface lies unused on Sunday, almost like the stones of St. Mark’s Square. But the people tread it rarely, out of customary shyness, and so only a thin web of human figures spreads over the wide surface; and the two colorful streams press on the sides; they quietly fill out the evening shadows emerging at the foot of buildings; black hats, light-colored men’s suits, and women’s colorful frippery form a dense, shiny ribbon, which, like a colorful snake, slides from the shelter of the buildings over the open, bright neighboring spaces. The whole thing is bathed in wonderful light; reddish dust seems to envelop everything, throughout the sky glows a pale blue. The buildings, whose colors fade slowly, are hit by the sun only here and there; they glow delicately and vividly, their gently moving elements define and form the wide space. In the distance out of the dark grey, a few of the windows of the palace glow in the sun, and under that flashes the bright yellow of a postal car.

Potsdamer Platz

Potsdamer Platz in the evening. Two large lamp poles with sparkling red arc lamps carve a gigantic dome of pointed arches in the heavy, thick air. Small and low flow the side streets therein, appearing to close not too far away. Especially low are Potsdam and Bellevue Streets with their trees that define a shallow vault between them. The front sides of the trees’ crowns shine in the bright light like green rocks with a thousand cavities, while the giant masses of linden trees on Leipziger Platz form dark, silent, distant mountains. The rim of the buildings shows subtle red and purple tones. People surge on the footpath, push their way on the bright, dry asphalt to tramways and carriages in eternal return. Their tops glisten in the light, but underneath they seem completely wrapped in darkness that covers the glare with a whitish haze. Sometimes the rush becomes so extraordinary that hardly a spot remains free, and those who come over the embankment appear to have emerged out of the sea, out of the waves of wheels and horses’ legs. And then a vehicle stops surprisingly close in front of the spectators and appears, as if by magic, big, clearly graspable, but also confused, a ghostlike presence of grey-andblack tones. Then it suddenly disappears again, a horse’s headp. 135 entirely fills the field of vision, his nostrils are wide open—the animal is breathing hard with strained shoulders—and the profile of the head thus looks as noble as an ancient bronze horse sculpture. Then the disarray dissolves all at once; the piece of asphalt in front of me seems to stretch into infinity; a bright light replaces the dark and chaotic fortress of wagons and is swallowed a moment later by the black crowd again. In the harsh, unfamiliar light, vehicles assume fantastical forms; a small automobile looks like a giant bumblebee; the thin spokes of carriage wheels—which look even thinner because of their blackness— under the massive box of the car are reminiscent of spider legs, the lanterns seem to hover freely over the black masses. And under all of this on the ground a wonderful world of shadows spreads out; they flit ghostlike over the surface with inexhaustible vitality.

In Front of the Brandenburg Gate

In front of the Brandenburg Gate on an autumn evening. The afterglow is extinguished, and the sky is completely filled with a mysteriously piercing blue after dusk. The balding trees form slightly reddish masses. Here too, two large lamp poles emanate a bright red light that is reflected by the tall columns of the gate. Through the openings one darkly sees the linden trees, coolly illuminated blue, and above them the approaching night. Only a few cornices of the small gatehouse, illuminated by red light, glow strangely and harshly out of the bluish picture between the columns. The wide plaza is covered with reddish veils created by the glare. The cars looking for the entrance seem to move as if at the bottom of the sea. They have lost all tangible reality. They seem to be made of clouds, shadows, and light. And in between, endless throngs, returning from Tiergarten from all sides, cross the plaza. People and crowds of cars merge here completely. The whole place is packed tight and appears as a unified being. Not even the ponderous mass of the trams can break the spell, so powerful are the light and the air, enveloping everything, connecting everything, fusing everything into a restlessly animated monstrous creature. Still, in spite of a thousand screams, all seems silent. The light drowns out the noise, one does not even notice it. What gives the whole a formidable quality are the marble balustrades and walls, which by day are hideous. They form the banks of this lake of light, and countless people—a silent, amazed, and solemn assembly, hardly recognizable in this fog of light—sit and stand against them. The large circle thereby acquires something truly majestic, a great and sublime beauty, on par with the noblest, capable of exercising power over the soul as only the strongest can and that the past gives to us in the form of tradition.

p. 136

These are just a few sketchy excerpts. This world should be depicted by a poet who could dedicate his entire energy and art to finding the most painterly, plastic, and vivid [anschaulich] words for this wonder. And it should be painted by painters who have the ability to convey form and color and space directly. Our painters (that is, painters in the sense discussed here) still go abroad to find themes. And it is understandable that the student tries to comprehend where the teachers have painted. It is forgivable that the landscape and the people appear painterly abroad, because they have already been made painterly. I am not familiar with Holland and I have never seen the silver Paris, and therefore I cannot compare. But I know French pictures well enough, and I have the feeling that we have different yet equal beauties that await discovery and conquest. Naturally, only patient study and experimentation can lead to this goal, only generations of painters will be able to provide an idea of the extent of this world. Only then could the beauty of the metropolis become a selfevident asset like the beauty of the mountains, plains, or lakes, and children will grow up in secure possession of this asset as we have grown up in possession of the beauty of the landscape. And only then can we hope that the power of comprehensive design [Gestalten] will grow with full force on the secure foundation of visual enjoyment.

p. 137