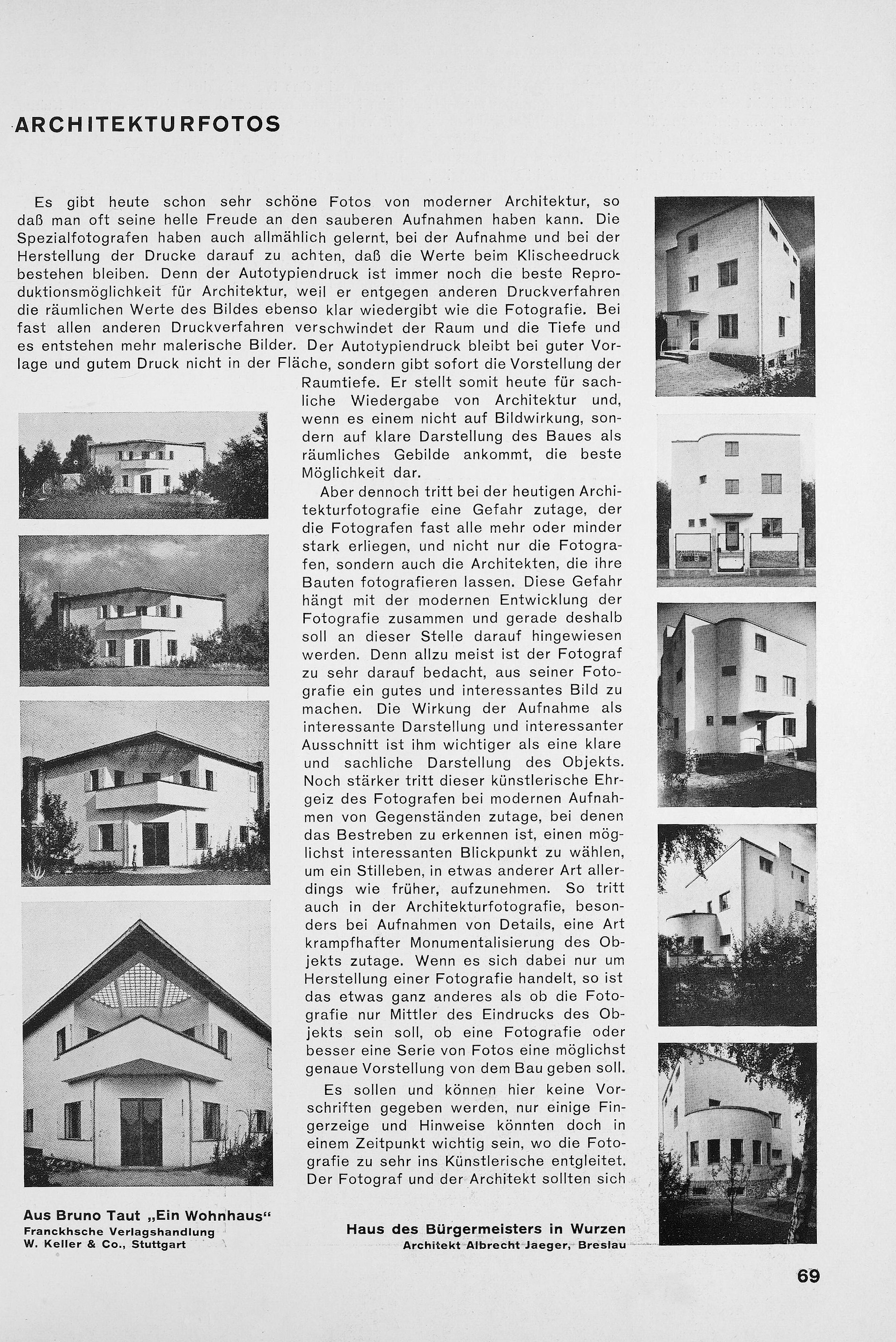

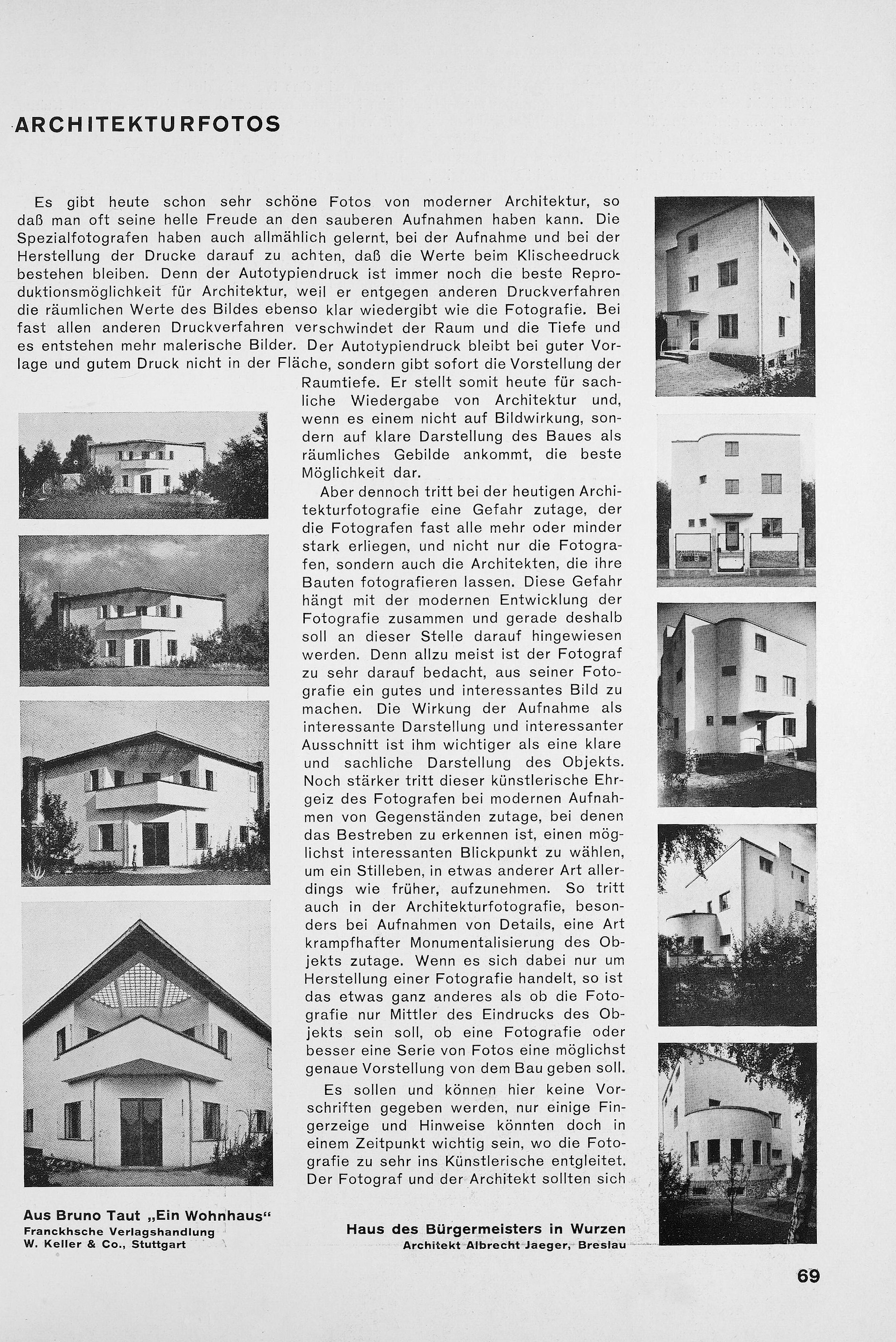

Figure 1 First page of Wilhelm Lotz, “Architekturfotos,” Die Form (February 1929). Left column: from Bruno Taut, Ein Wohnhaus [1927]. Right column: Albrecht Jaeger, Haus des Bürgermeisters, Wurzen.

p. 103Today there are so many beautiful photographs of modern

architecture that one can regularly revel in immaculate pictures.

Professional photographs have slowly learned to attend, in

their exposures and their prints, to the proper values for the

final printed image. Indeed, autotypes remain the best reproduction

option for architecture; for, compared to other printing

processes, they render spatial values as well as actual photographic

prints. In nearly all other printing processes, space and

depth disappear, resulting in more painterly [malerische] images.

With a good template and printer, autotypes are not restricted

to the surface but immediately provide the impression of deep

space. For the objective [sachlich] reproduction of architecture—

that is, from the perspective not of visual impact but of

clear presentation of buildings as spatial structures—autotypes

are the best option.

First page of Wilhelm Lotz, “Architekturfotos,” Die Form (February 1929). Left column: from Bruno Taut, Ein Wohnhaus [1927]. Right column: Albrecht Jaeger, Haus des Bürgermeisters, Wurzen.

p. 103Today there are so many beautiful photographs of modern

architecture that one can regularly revel in immaculate pictures.

Professional photographs have slowly learned to attend, in

their exposures and their prints, to the proper values for the

final printed image. Indeed, autotypes remain the best reproduction

option for architecture; for, compared to other printing

processes, they render spatial values as well as actual photographic

prints. In nearly all other printing processes, space and

depth disappear, resulting in more painterly [malerische] images.

With a good template and printer, autotypes are not restricted

to the surface but immediately provide the impression of deep

space. For the objective [sachlich] reproduction of architecture—

that is, from the perspective not of visual impact but of

clear presentation of buildings as spatial structures—autotypes

are the best option.

And yet a danger is evident in current architecture photography—

one to which nearly all photographers succumb to

varying degrees, and not only the photographers but the architects

who have their buildings photographed. This danger is

linked to the modern development of photography and thus

warrants discussion here. For all too often the photographer

is anxious to turn his photographs into good and interesting

pictures. To him the impression the photograph makes as an

interesting representation and an interesting detail is more

important than a clear and objective [sachlich] representation

of the object. Such artistic ambitions on the part of the photographer

are even more evident when accompanied by a noticeable

effort to choose the most interesting possible viewpoint in

order to make what amounts to a still life, albeit differently

than before. Accordingly, we find in architecture photography

a convulsive monumentalization of objects, especially in the

capturing of details. If it were only a question of taking photographs,

it would be entirely different than when we understand

photography exclusively as a transmitter of impressions

of objects; that is, if we understand a photograph—or, better, a

series of photographs—as providing the most precise possible

conception of a building.

This is not the place to lay down rules, but only a few important

pointers and tips for those moments when photographers

risk sliding into the artistic. Photographers and architects should

always ask themselves whether the envisioned photographs

will produce the most objective [sachlich] possible representation—

and then photograph from this vantage point. Perhaps

we must even establish a norm whereby we orient ourselves

toward the cardinal directions more than toward interesting p. 104 pictures and details. Just as one always indicates the cardinal

directions on a site plan, so too one should indicate on every

photograph the cardinal direction from which the photograph

was taken. This would be especially beneficial for residential

buildings. We illustrate two attempts that are of interest insofar

as they offer an interlink to—or, better, an approximation of—

filmic representation. First, the photographer of a house by

[Bruno] Taut advanced toward it incrementally from the countryside

so that one perceives how it becomes more and more

like a cube as one approaches it from a distance. In the second

example, the photographer circled the house with his camera.

By surveying the five ensuing photographs, one gains a sense

of the house’s corporeal physicality [Körperlichkeit]. For the

representation of architectural objects, similar strips of images

[Bildstreifen] may productively supplement larger pictures,

which better show details. As people prepare to mount a photography

exhibition in Stuttgart [namely, Film und Fotografie

or Fifo], they should consider these viewpoints and seek out

options. Above all, they should consider the task of photography

as the transmitter of impressions of objects.