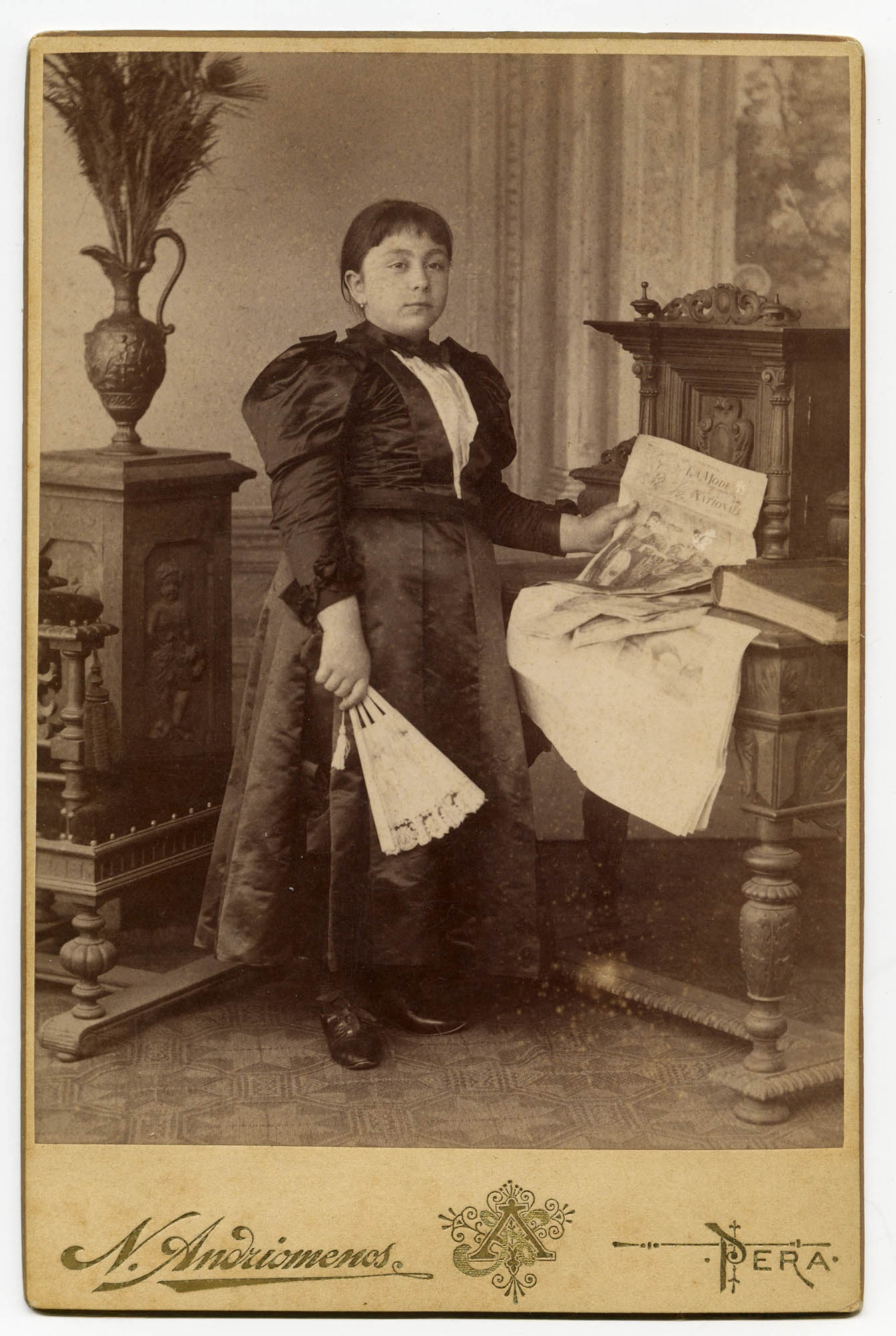

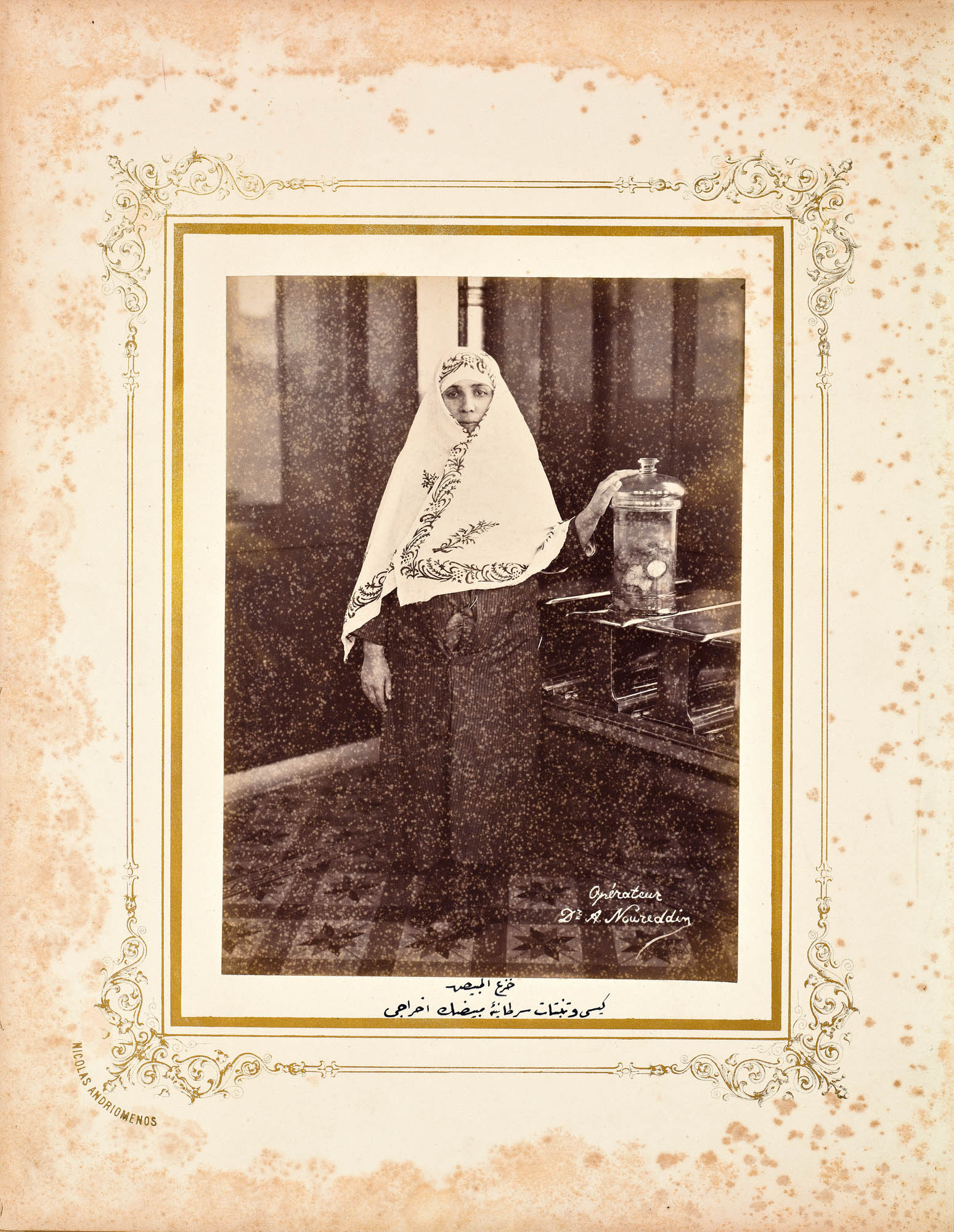

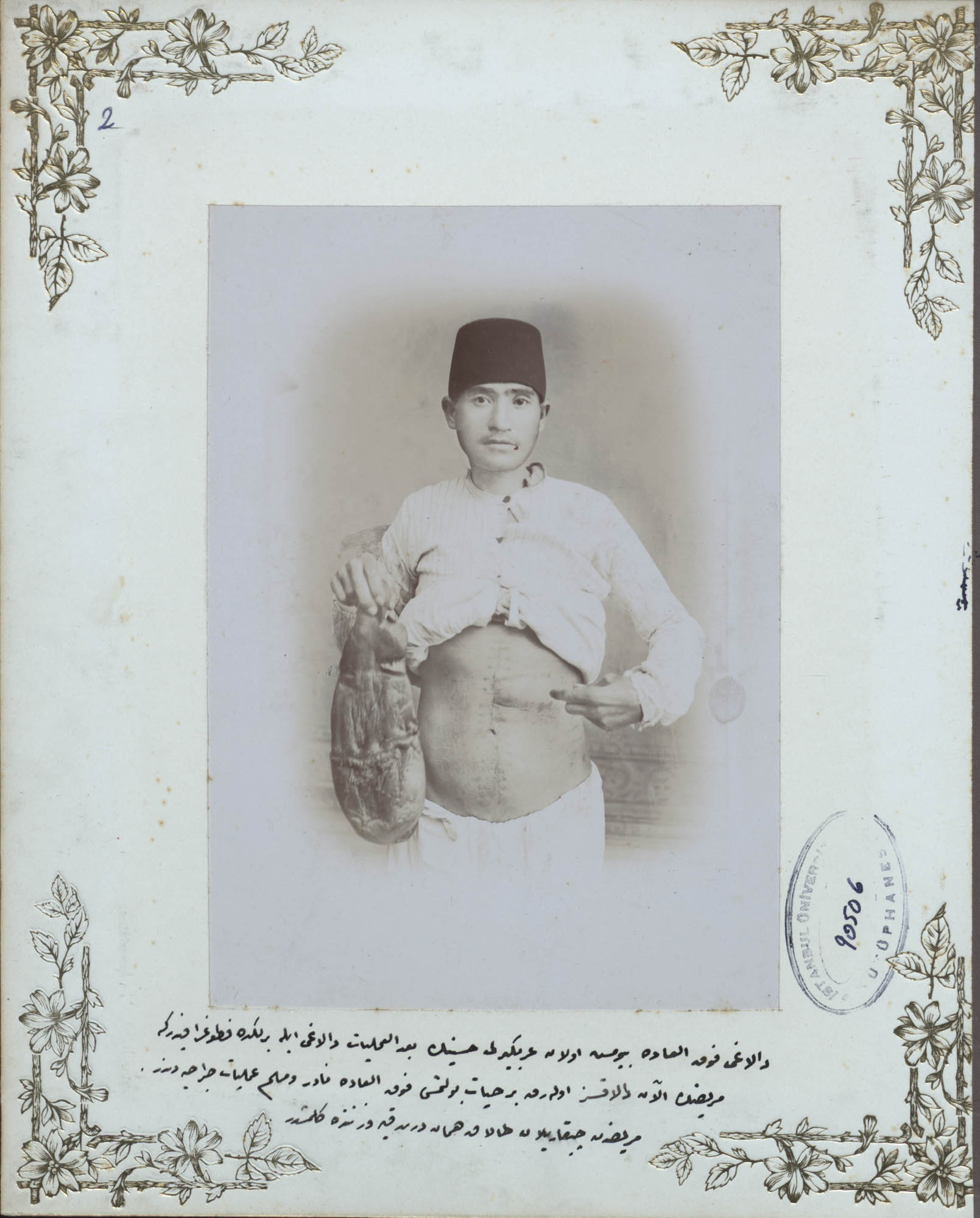

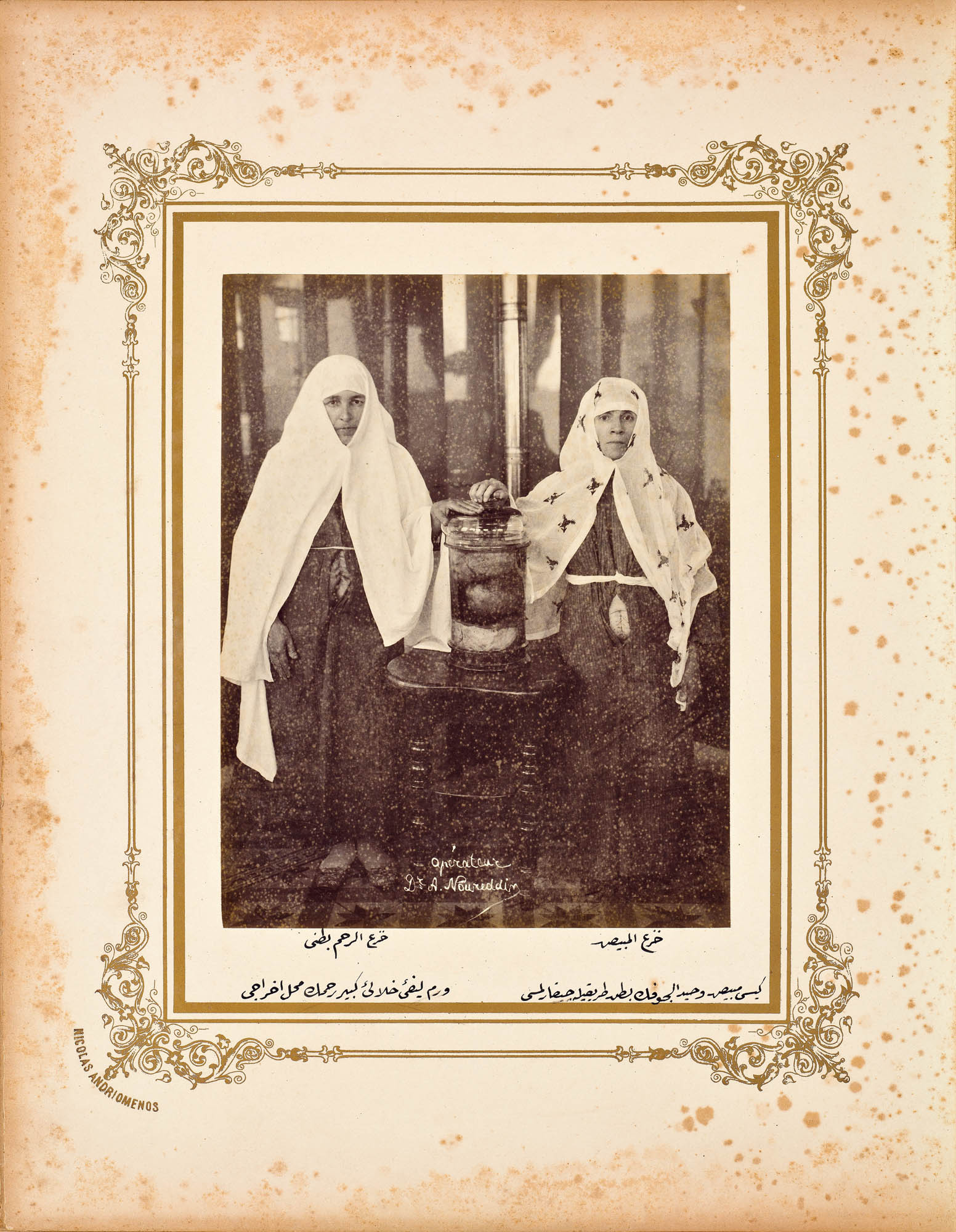

Figure 1 Nicolas Andriomenos. Tensüf

Kadın, ca. 1890–1894. Image 1,

Haseki Women’s Hospital album

formerly part of Abdülhamīd II’s

Yıldız Palace collection. This is

the first photograph in the Haseki

Women’s Hospital album compiled

by Dr. Ahmed Nurrettin and

sent to Sultan Abdülhamīd II.

İstanbul Üniversitesi Nadir

Eserler Kütüphanesi (Istanbul

University Library of Rare Books).p. 37

I still remember the afternoon I encountered the portraits of seven women

who had been treated at Haseki Women’s Hospital (Haseki Nisa Hastanesi),

Istanbul. It was August 2009, and the gold-embossed insignia of Ottoman

Sultan Abdülhamīd II was still perfectly intact on the century-old photo

album’s crimson velvet cover. I could not possibly have known, as I

turned to the first portrait, how much this album (which I will refer to as

the Haseki portrait album) would teach me not only about photography

and late Ottoman healthcare but about how the questions we ask as

scholars shape the answers we discover. The very questions we ask make

some historical experiences discoverable and, unbeknownst to us, obscure

traces of others.

Nicolas Andriomenos. Tensüf

Kadın, ca. 1890–1894. Image 1,

Haseki Women’s Hospital album

formerly part of Abdülhamīd II’s

Yıldız Palace collection. This is

the first photograph in the Haseki

Women’s Hospital album compiled

by Dr. Ahmed Nurrettin and

sent to Sultan Abdülhamīd II.

İstanbul Üniversitesi Nadir

Eserler Kütüphanesi (Istanbul

University Library of Rare Books).p. 37

I still remember the afternoon I encountered the portraits of seven women

who had been treated at Haseki Women’s Hospital (Haseki Nisa Hastanesi),

Istanbul. It was August 2009, and the gold-embossed insignia of Ottoman

Sultan Abdülhamīd II was still perfectly intact on the century-old photo

album’s crimson velvet cover. I could not possibly have known, as I

turned to the first portrait, how much this album (which I will refer to as

the Haseki portrait album) would teach me not only about photography

and late Ottoman healthcare but about how the questions we ask as

scholars shape the answers we discover. The very questions we ask make

some historical experiences discoverable and, unbeknownst to us, obscure

traces of others.

This article tells the story of how I learned to look at these extraordinary

photographs and reflect on the medical care visualized in them. In

what follows, I have deliberately sought to share my process of discovery

rather than present the historical knowledge attained at the end, in the

hopes of encouraging visual research that not only situates visuals in

sociocultural and political contexts but renders visible the construction

of what one might call “the possibility of visual history.”1 Hence I attempt

to share how certain signs on a photographic surface transformed into

clues that sparked my imagination and in turn allowed me to see in ways

not available to me before.

If what follows is a detective narrative of sorts, it is one in which I

have highlighted the moments in which visual detection became possible,

often in conversation with others. This is a detective story focused

less on the discovery at the end and more on the process by which specific

visual details emerged as clues. Humbling as it is to admit, most of

the clues that would emerge over the course of almost a decade of study

were visible to me that afternoon in 2009. But I could neither see them

nor comprehend their significance. This then is a story of how clues

become detectable as clues.2

p. 38 Abdülhamīd II reigned from 1876 to 1909. These were critical and

tumultuous years in Ottoman history. The Haseki portrait album is part

of the rich collection of photographs amassed in Istanbul’s Yıldız Palace

during the sultan’s reign, comprising some 911 albums containing 35,000

photographs.3 However, this particular album (unlike many others in the

collection) is not one that was commissioned by the sultan. Rather, it was

sent to the palace by an ambitious young doctor, Ahmed Nurettin, gynecologist

and obstetrician of Haseki Women’s Hospital.

Haseki Women’s Hospital was a medical institution with a history

going back to the sixteenth century.4 For a while it functioned as a

women’s prison as well. In 1868 it was formally established as a women’s

hospital, the only such institution in the entire Ottoman Empire. At a

time when most women received medical treatment in their homes,

Haseki served mainly homeless and indigent women.5 Medical historian

Gülhan Balsoy details the multiple functions of the hospital, emphasizing

the dual role of Haseki as a place that sheltered and cared for the

most vulnerable Ottoman women while also keeping these unsuitable

women away from public spaces. Haseki Hospital as a social institution

was a site of both care and control, for the patients individually as well

as for the empire. Hence the Haseki portrait album is particularly valuable

as a historical trace of how the visibility and vulnerability of female

patients as both medical and imperial subjects were negotiated.

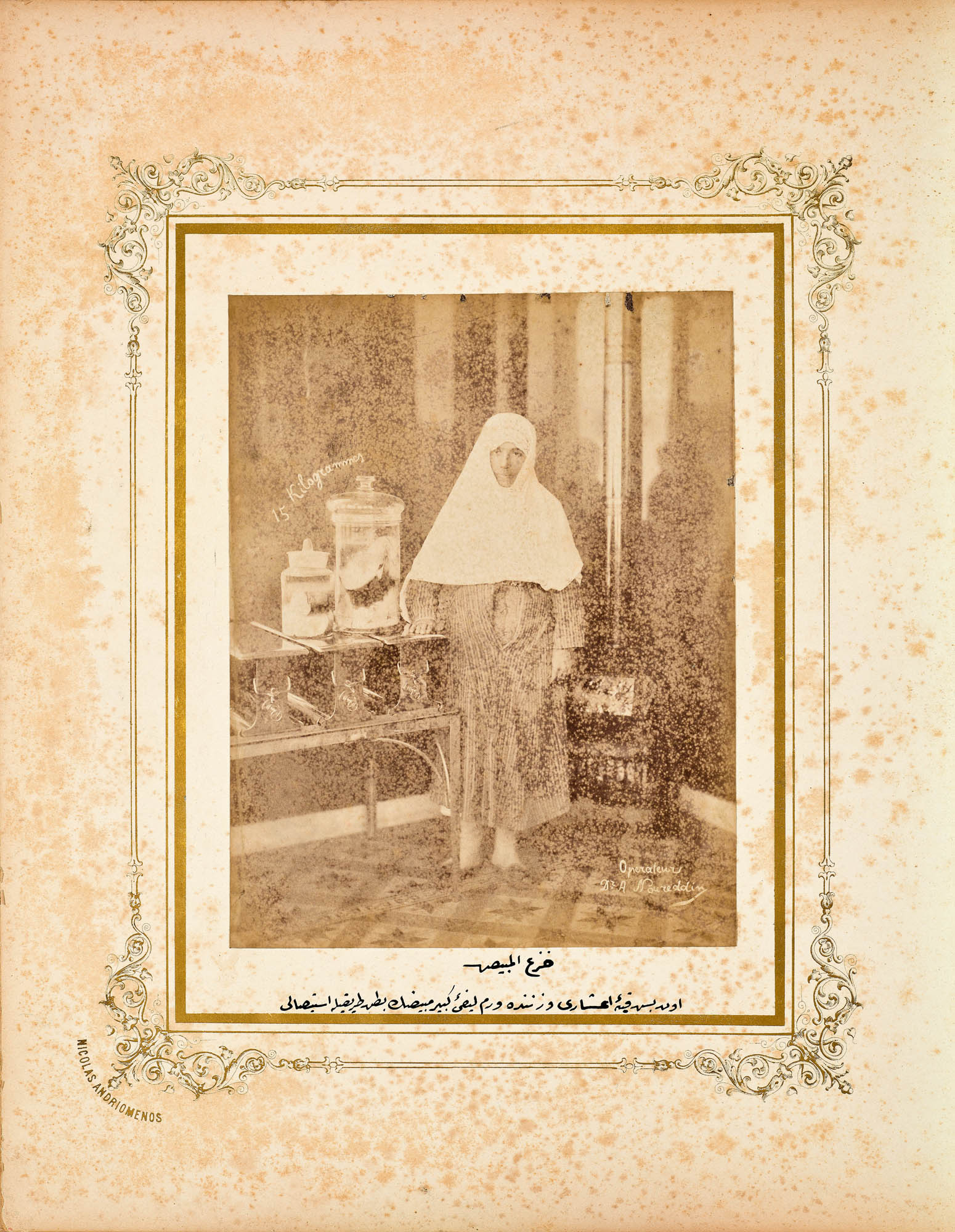

The Haseki album consists of eight plates. What is perhaps most striking

about the first six is how much they look like classic studio portraits

of the late nineteenth century. In each we can clearly see a woman

directly facing the camera. She stands on a carpet with a stylized studio

backdrop behind her and a decorative table to her side. Each photograph

is mounted onto an ornate mat with the photographer’s name—Nicolas

Andriomenos—imprinted on it. All these details attest to the genre of

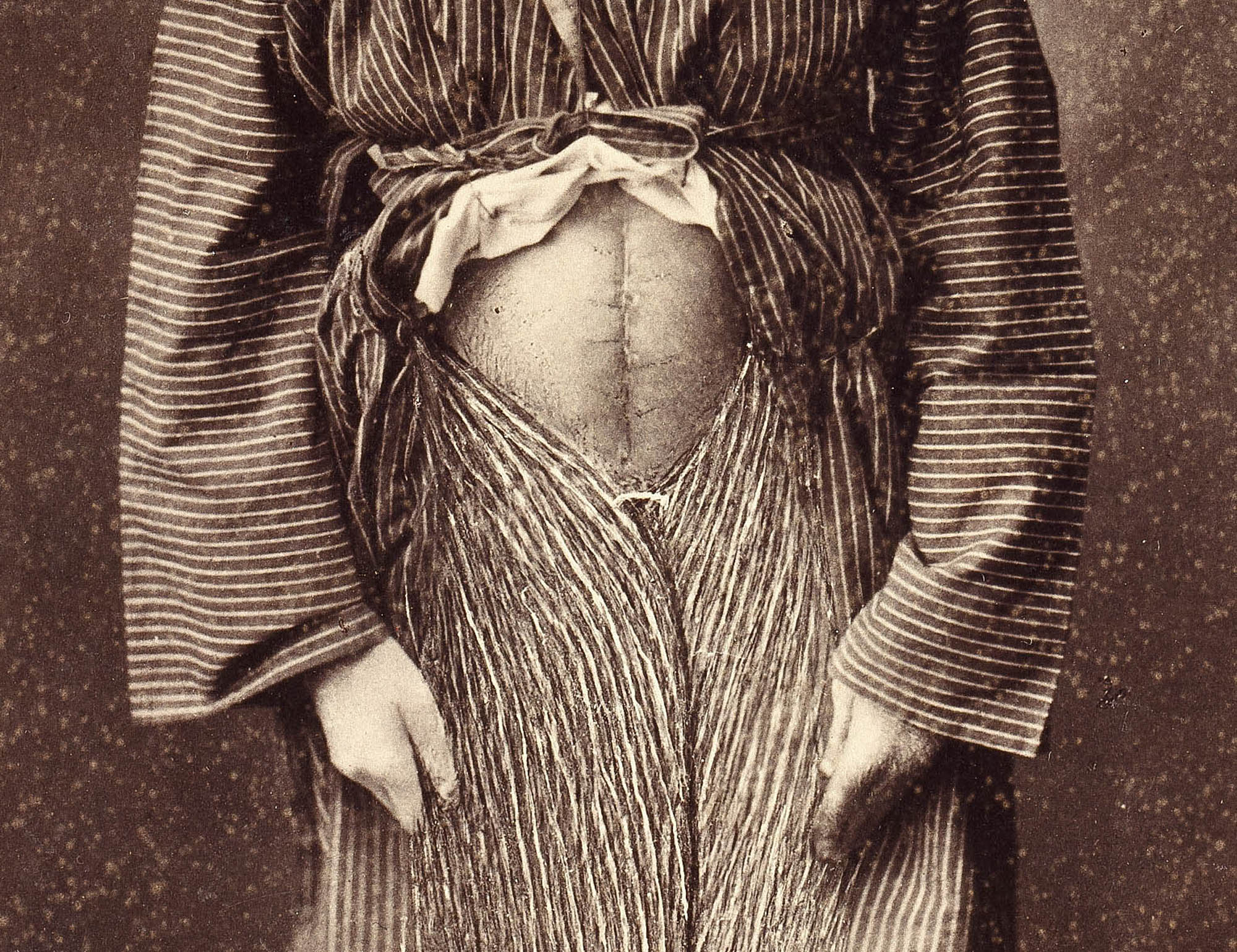

this image as a studio portrait. Figure 2 Nicolas Andriomenos. Tensüf

Kadın, ca. 1890–1894. Image 1,

Haseki Women’s Hospital album

formerly part of Abdülhamīd II’s

Yıldız Palace collection. Detail

from the opening image of

the album showing a median

laparotomy scar and the tumor

removed in the surgery. İstanbul

Üniversitesi Nadir Eserler

Kütüphanesi (Istanbul University

Library of Rare Books).

Nicolas Andriomenos. Tensüf

Kadın, ca. 1890–1894. Image 1,

Haseki Women’s Hospital album

formerly part of Abdülhamīd II’s

Yıldız Palace collection. Detail

from the opening image of

the album showing a median

laparotomy scar and the tumor

removed in the surgery. İstanbul

Üniversitesi Nadir Eserler

Kütüphanesi (Istanbul University

Library of Rare Books).

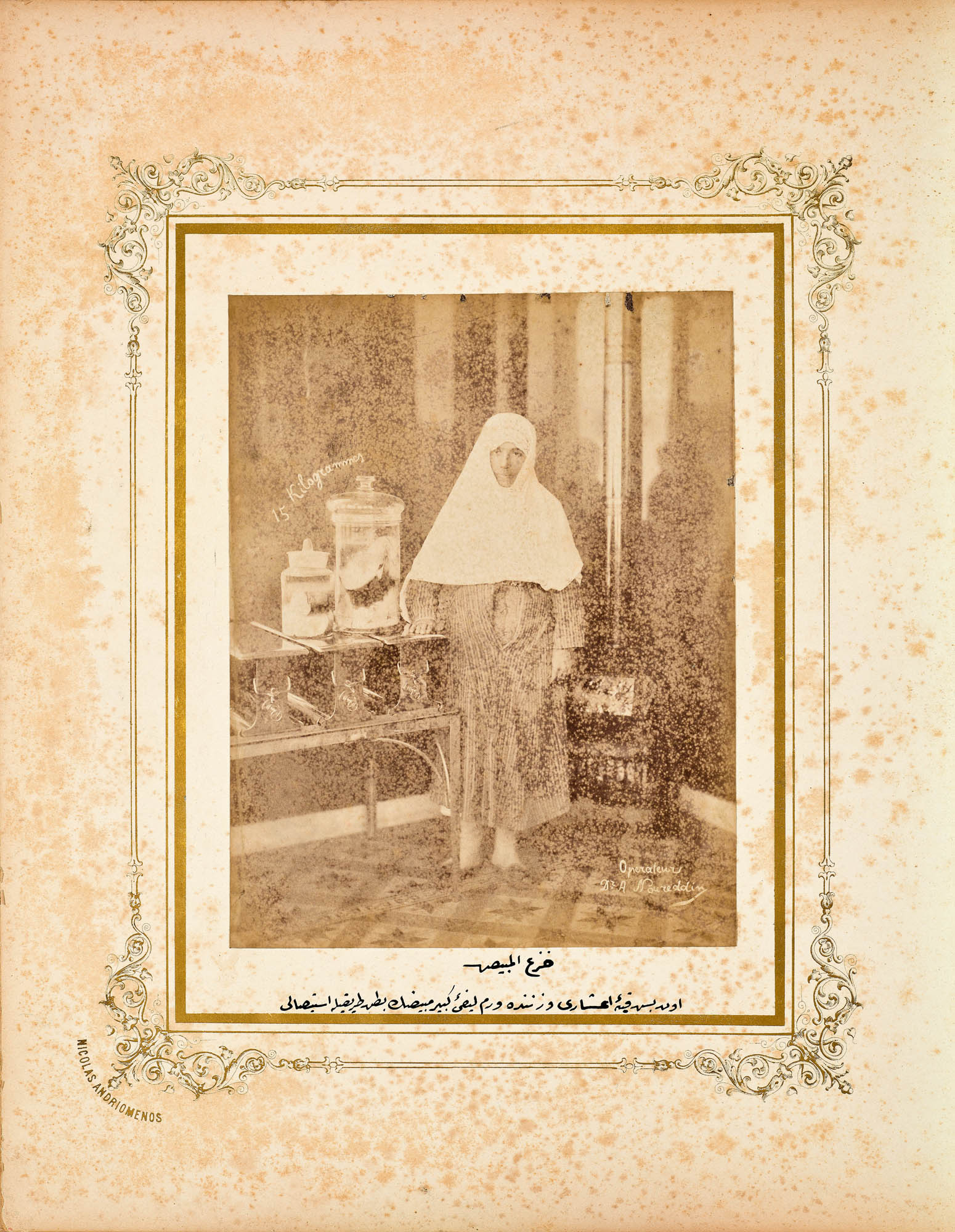

The caption under the first portrait reads, “40 year old negroid [zenciye]

resident of Kasımpaşa, Tensüf Kadın’s ‘picture of health’ following a

median laparotomy resulting in the complete removal of the tumor and

uterus.” Indeed, Tensüf Kadın is wearing a hospital-issued gown carefully

pinned open to reveal the laparotomy scar on her abdomen. And on

the decorative table beside her, in lieu of the typical stack of books or

vase of spring blossoms, is a specimen jar containing the tumor that was

removed from her, thus displaying to her, the photographer, possibly to p. 39 the sultan, and now to us, that which was once internal to her and hence

invisible. That the album opens with a photograph of a black woman is

noteworthy. Tensüf Kadın is the only black female patient in the album

sent to the sultan. The issue of how race is represented in this album and

more broadly in Ottoman photography is outside the scope of this article

but is an important topic that deserves much more research.6

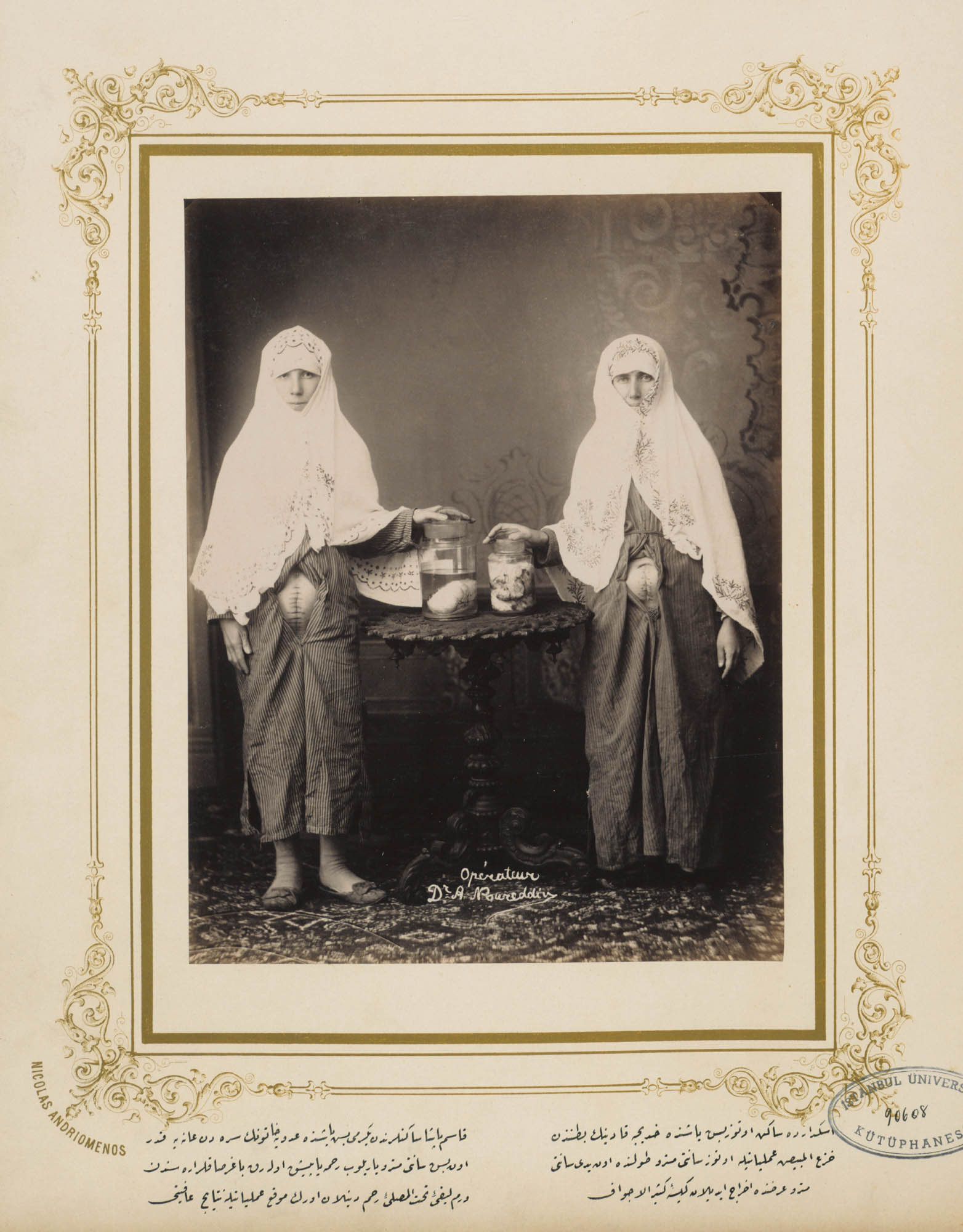

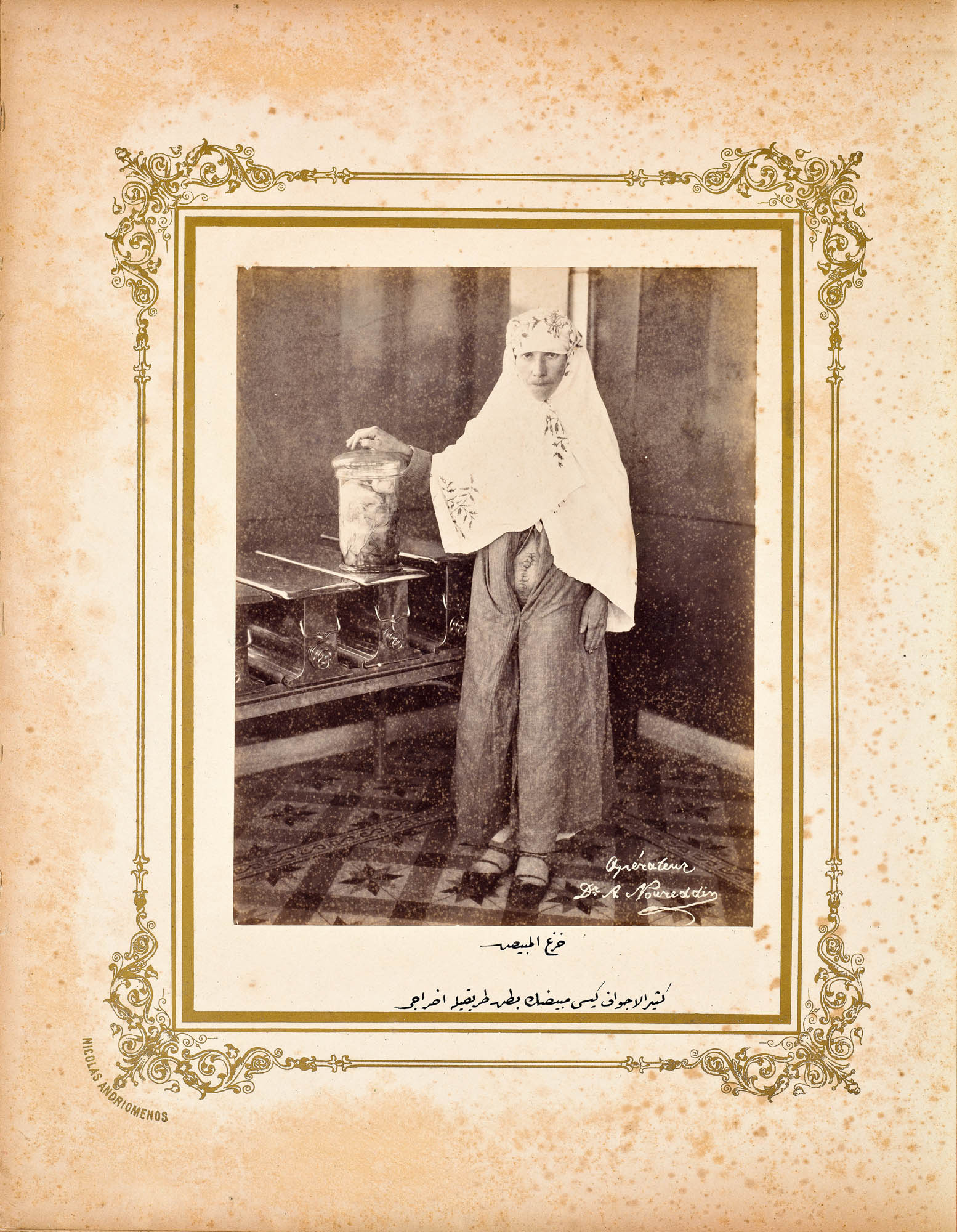

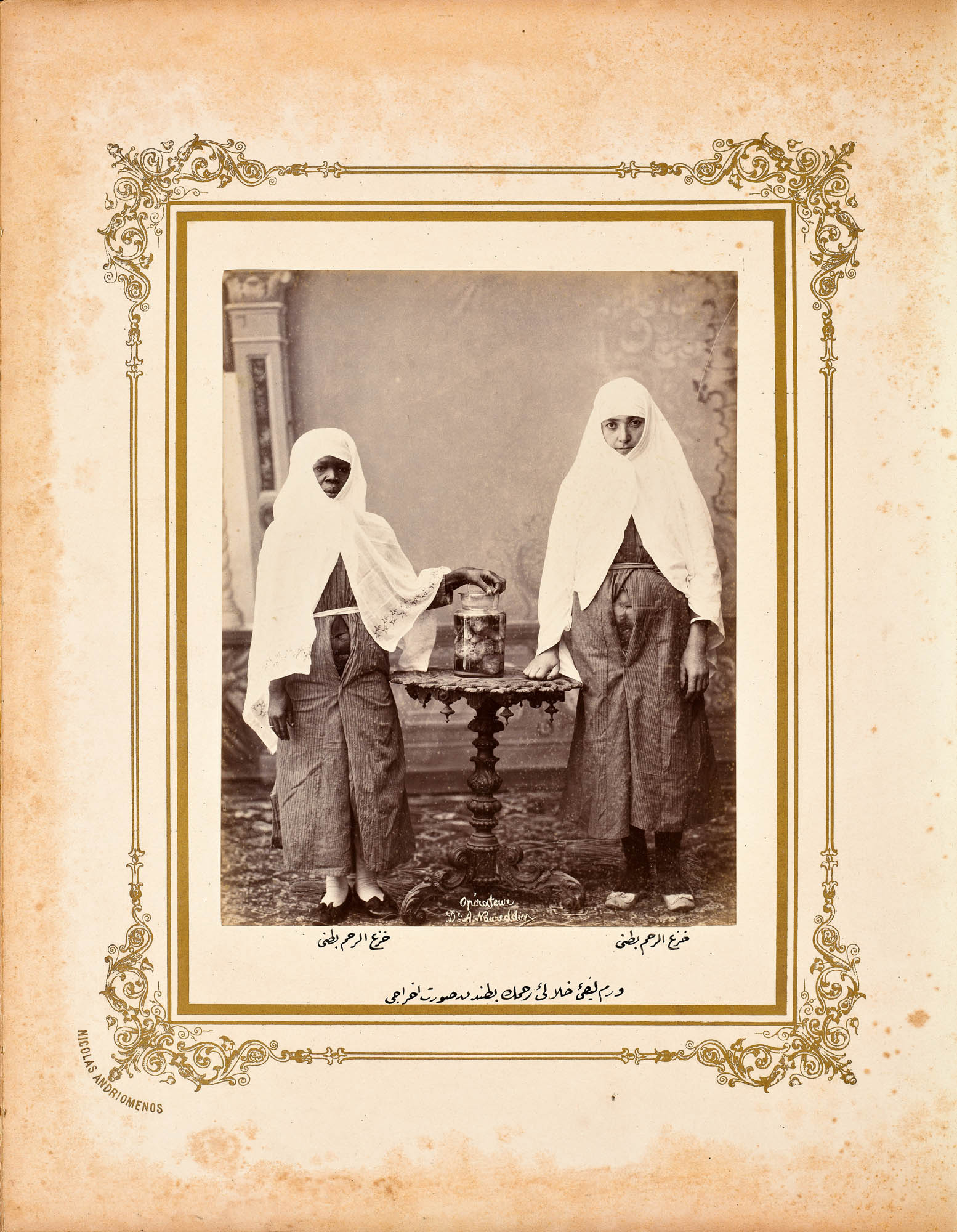

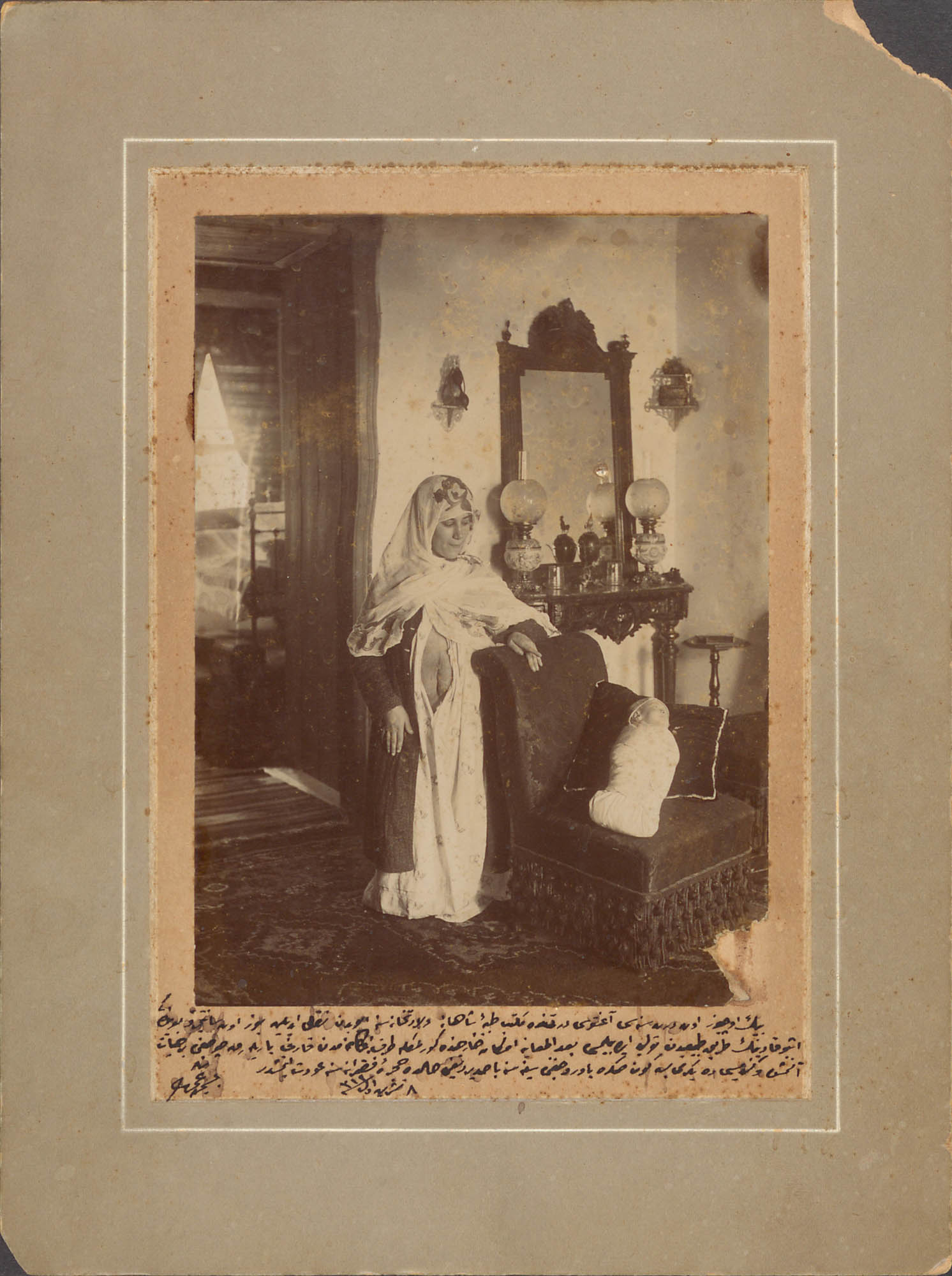

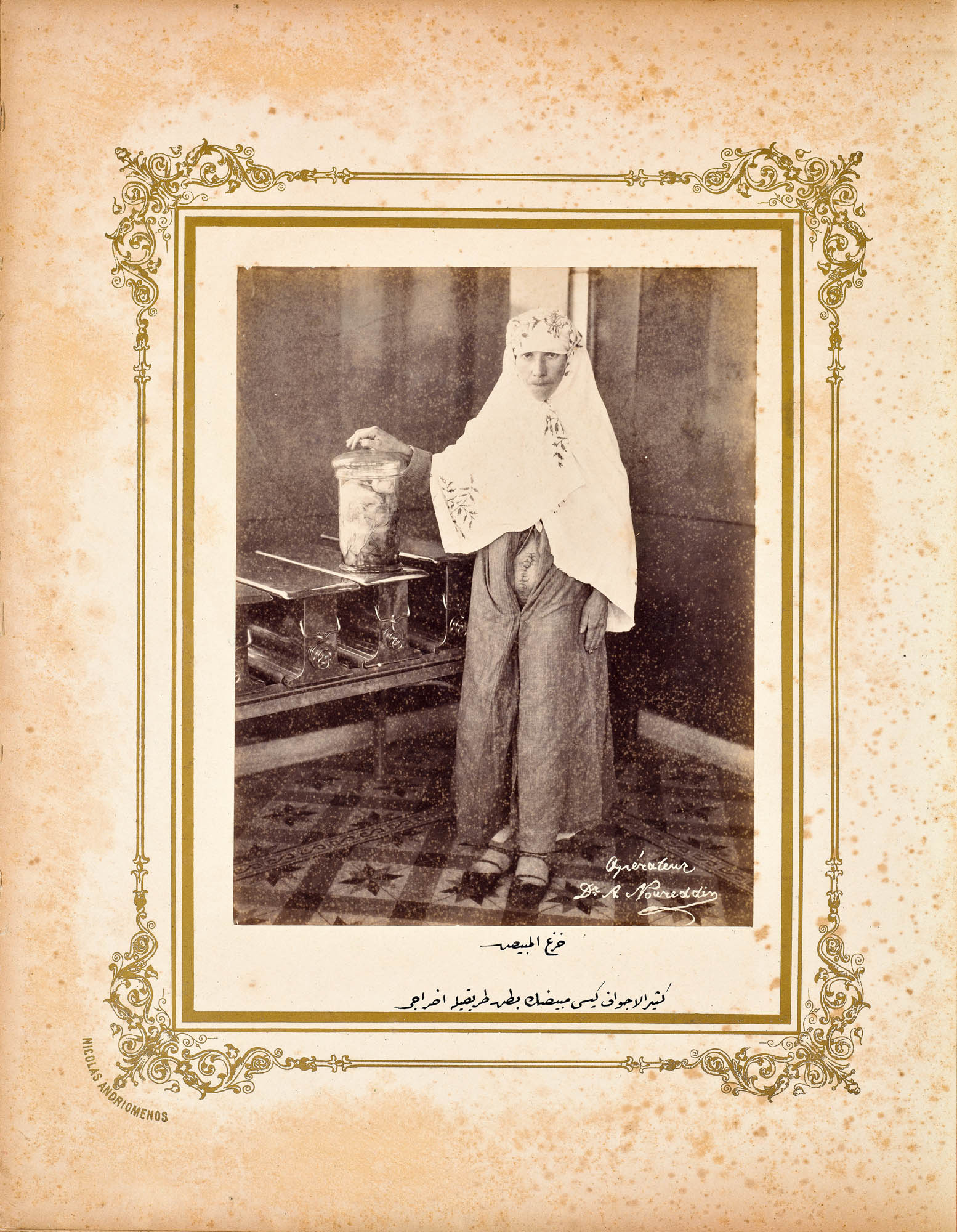

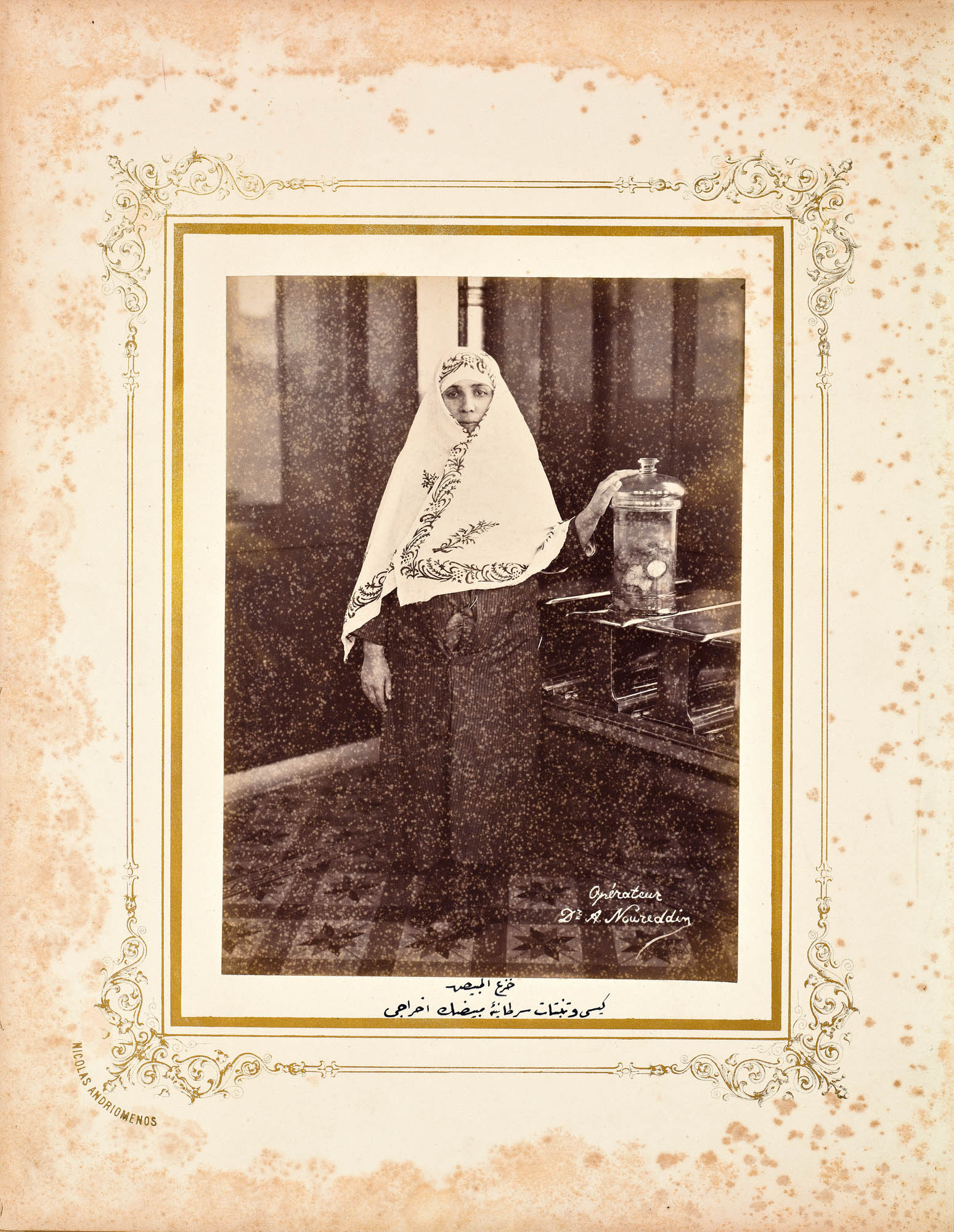

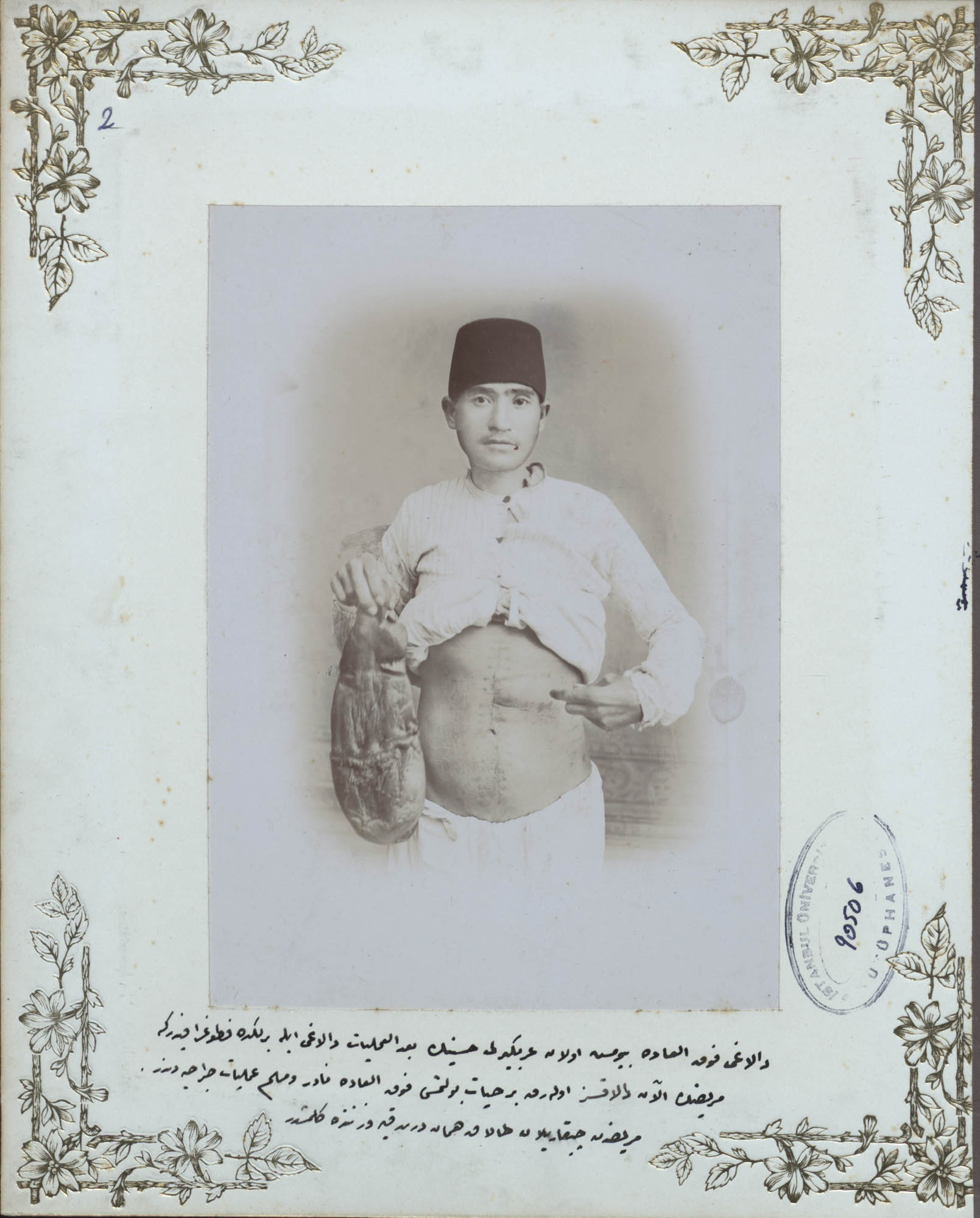

Figure 3 Nicolas Andriomenos.

Müzeyyen Hatun, ca. 1890–1894.

Image 2, Haseki Women’s

Hospital album formerly part of

Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız Palace

collection. İstanbul Üniversitesi

Nadir Eserler Kütüphanesi

(Istanbul University Library of

Rare Books).Figure 4

Nicolas Andriomenos.

Müzeyyen Hatun, ca. 1890–1894.

Image 2, Haseki Women’s

Hospital album formerly part of

Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız Palace

collection. İstanbul Üniversitesi

Nadir Eserler Kütüphanesi

(Istanbul University Library of

Rare Books).Figure 4 Nicolas Andriomenos.

Ayşe Hatun, ca. 1890–1894.

Image 3, Haseki Women’s

Hospital album formerly part of

Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız Palace

collection. İstanbul Üniversitesi

Nadir Eserler Kütüphanesi

(Istanbul University Library of

Rare Books).

Nicolas Andriomenos.

Ayşe Hatun, ca. 1890–1894.

Image 3, Haseki Women’s

Hospital album formerly part of

Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız Palace

collection. İstanbul Üniversitesi

Nadir Eserler Kütüphanesi

(Istanbul University Library of

Rare Books).

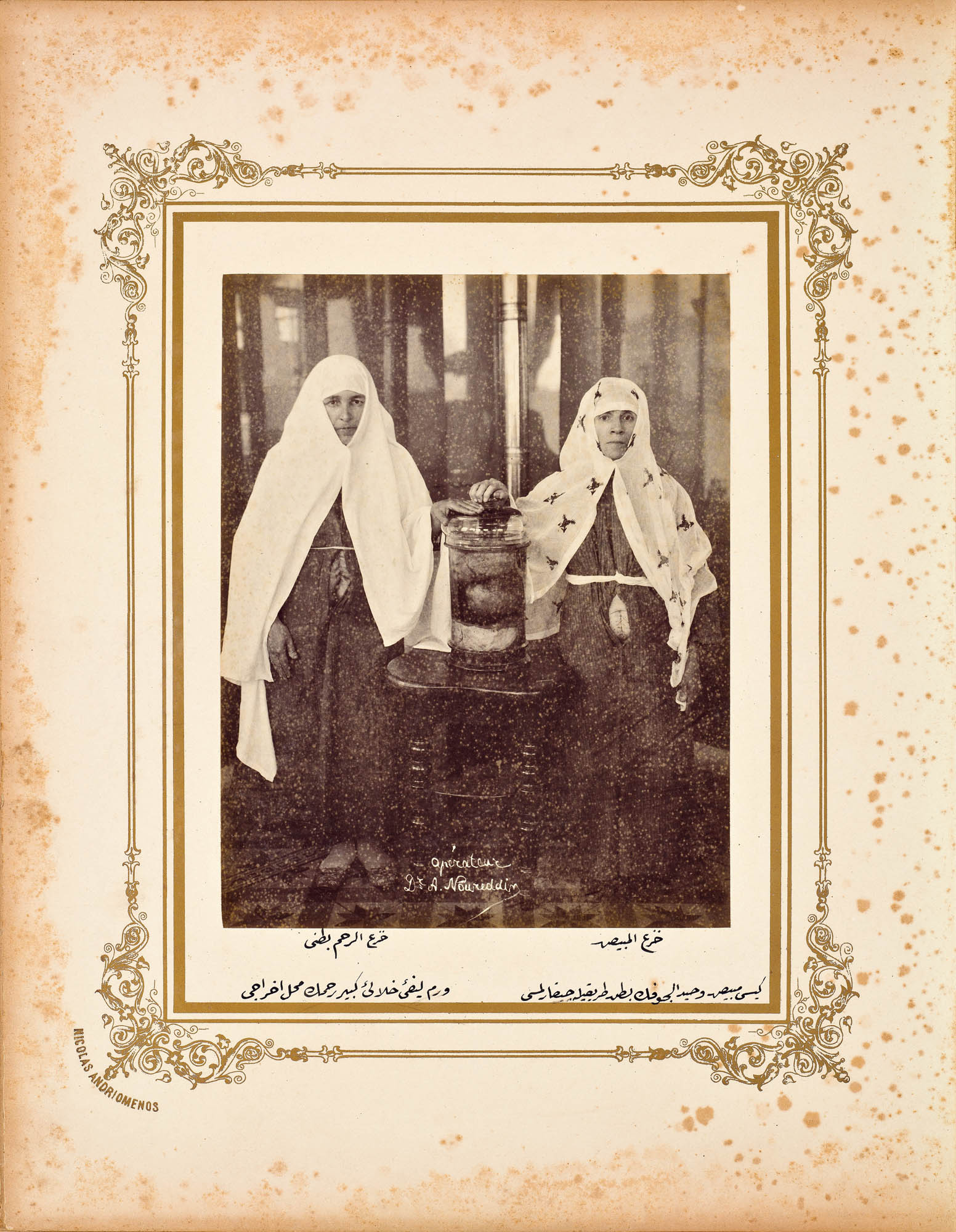

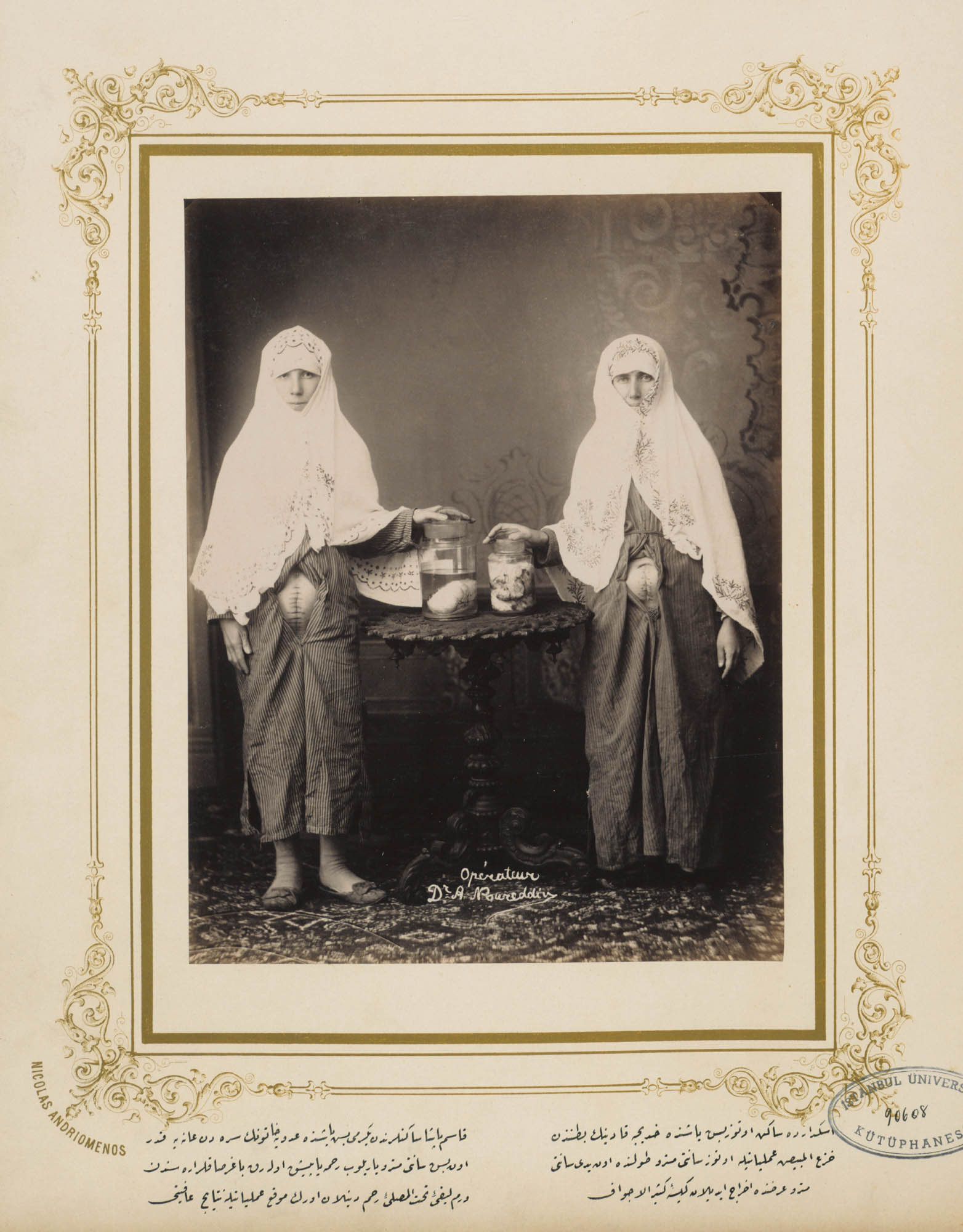

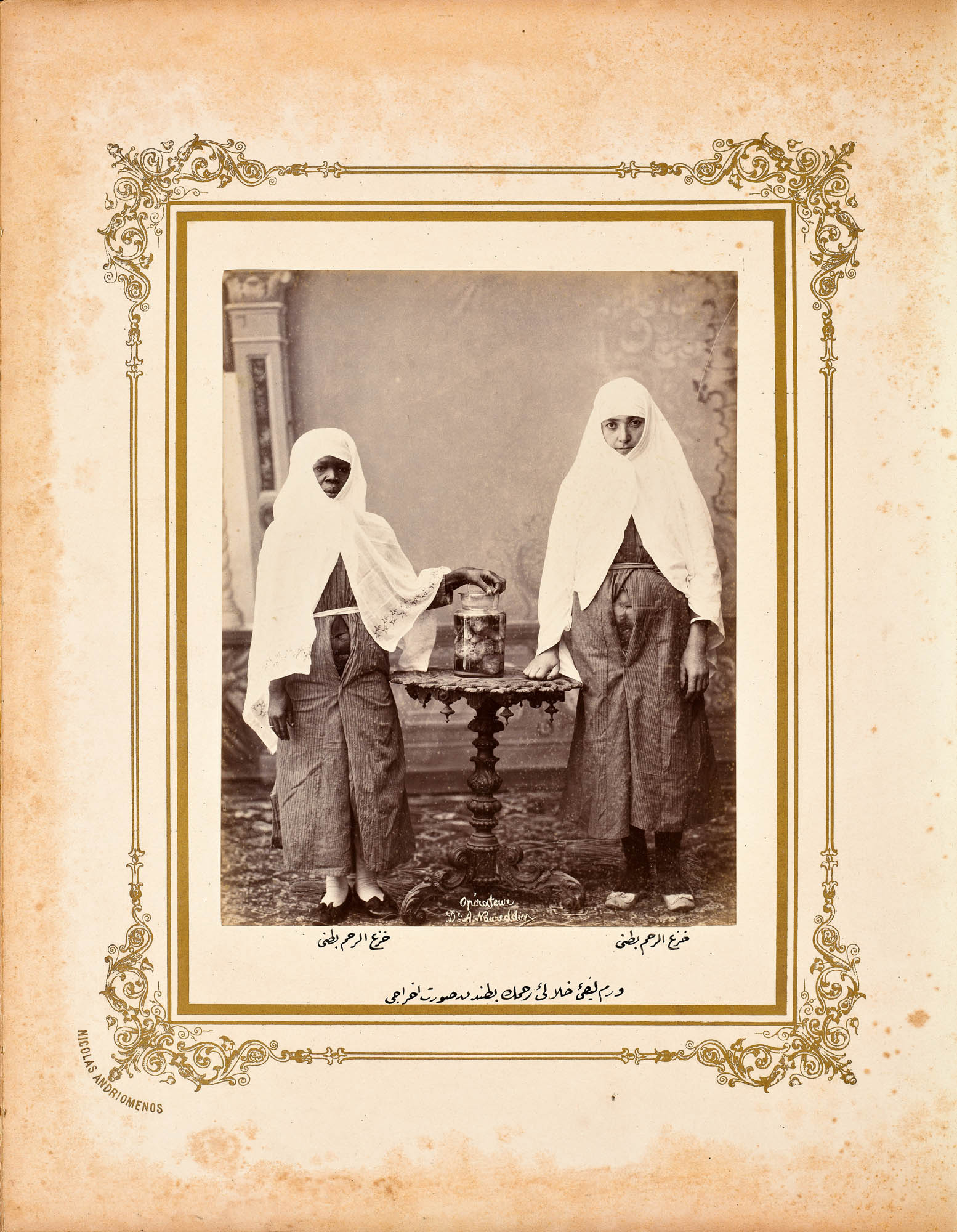

With minor variations, the portraits are all similar: the women appear

in full hospital uniform, all but Tensüf Kadın wear slippers, and each

caption contains detailed information about the patient and what exactly

was removed in the surgical process. Some include the dimensions or

weight of the tumor: Müzeyyen Hatun’s tumor weighed over three kilograms.

Each plate bears the surgeon’s name and title in French visible

in the right-hand corner: “Opérateur Dr. A.

Noureddin.”7 Gülizar Hatun’s portrait is the

exception. Gülizar had a caesarean to remove

the fetus who had died in her womb. She is photographed

without an ornate table, and whether

there is a backdrop behind her or merely a draped

sheet is hard to determine. Hatice Kadın and Adviye

Hatun are posed together. In each of the accompanying

captions, the portraits are described as “a

picture of health.” The image of Misli Hatun is

described as her “asar-ısşifa” (state of healing) after

a twenty-by-thirty-centimeter tumor was removed

through a twenty-five-centimeter incision.

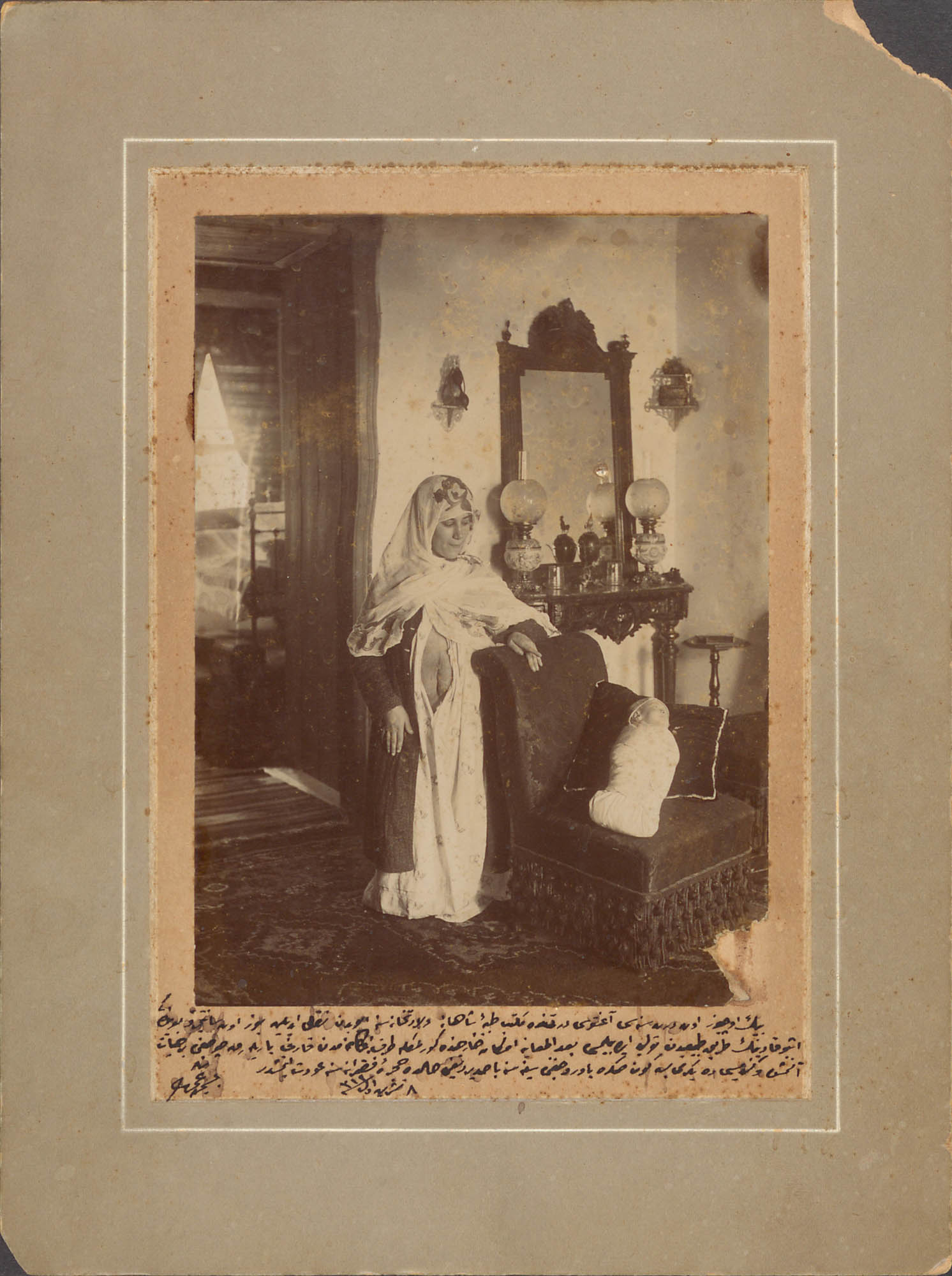

Figure 5 Nicolas Andriomenos or

unknown photographer. Gülizar

Kadın, ca. 1890–1891. Image 4,

Haseki Women’s Hospital album

formerly part of Abdülhamīd II’s

Yıldız Palace collection. “Picture

of health” of twenty-two-year-old

Gülizar Kadın, whose child had

died in the womb, taken after her

caesarean surgery. Gülizar’s case

was communicated to Sultan

Abdülhamīd II by letter from an

Ottoman municipal health officer

the morning after her surgery.

This is the only portrait in the

album showing only the patient.

İstanbul Üniversitesi Nadir

Eserler Kütüphanesi (Istanbul

University Library of Rare Books).Figure 6

Nicolas Andriomenos or

unknown photographer. Gülizar

Kadın, ca. 1890–1891. Image 4,

Haseki Women’s Hospital album

formerly part of Abdülhamīd II’s

Yıldız Palace collection. “Picture

of health” of twenty-two-year-old

Gülizar Kadın, whose child had

died in the womb, taken after her

caesarean surgery. Gülizar’s case

was communicated to Sultan

Abdülhamīd II by letter from an

Ottoman municipal health officer

the morning after her surgery.

This is the only portrait in the

album showing only the patient.

İstanbul Üniversitesi Nadir

Eserler Kütüphanesi (Istanbul

University Library of Rare Books).Figure 6 Nicolas Andriomenos. Hatice Kadın and Adviye Hatun,

ca. 1890–1894. Image 5, Haseki

Women’s Hospital album formerly

part of Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız

Palace collection. İstanbul Üniversitesi

Nadir Eserler Kütüphanesi

(Istanbul University Library of

Rare Books).Figure 7

Nicolas Andriomenos. Hatice Kadın and Adviye Hatun,

ca. 1890–1894. Image 5, Haseki

Women’s Hospital album formerly

part of Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız

Palace collection. İstanbul Üniversitesi

Nadir Eserler Kütüphanesi

(Istanbul University Library of

Rare Books).Figure 7 Nicolas Andriomenos. Misli Hatun, ca.

1890–1894. Image 6, Haseki

Women’s Hospital album formerly

part of Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız

Palace collection. İstanbul Üniversitesi

Nadir Eserler Kütüphanesi

(Istanbul University Library of

Rare Books).

Nicolas Andriomenos. Misli Hatun, ca.

1890–1894. Image 6, Haseki

Women’s Hospital album formerly

part of Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız

Palace collection. İstanbul Üniversitesi

Nadir Eserler Kütüphanesi

(Istanbul University Library of

Rare Books).

In total, six variations of the phrase “picture of

health” are used: “landscape of health,” “condition

of a scar,” “sign of healing,” “a picture of health,”

“image of convalescence,” and “state of healing.”8

This linguistic care suggests that drawing attention

to the women’s recovered health was a central

purpose of the album. These are not images of

pathology but photographs that visualize successful

medical care. Not only do they render visible

that which was once internal to the body, a novelty

before the invention of X-ray technology in

1895, but these photographs serve as evidence of

the efficacy of medical procedures; these are photographs

of regained health.

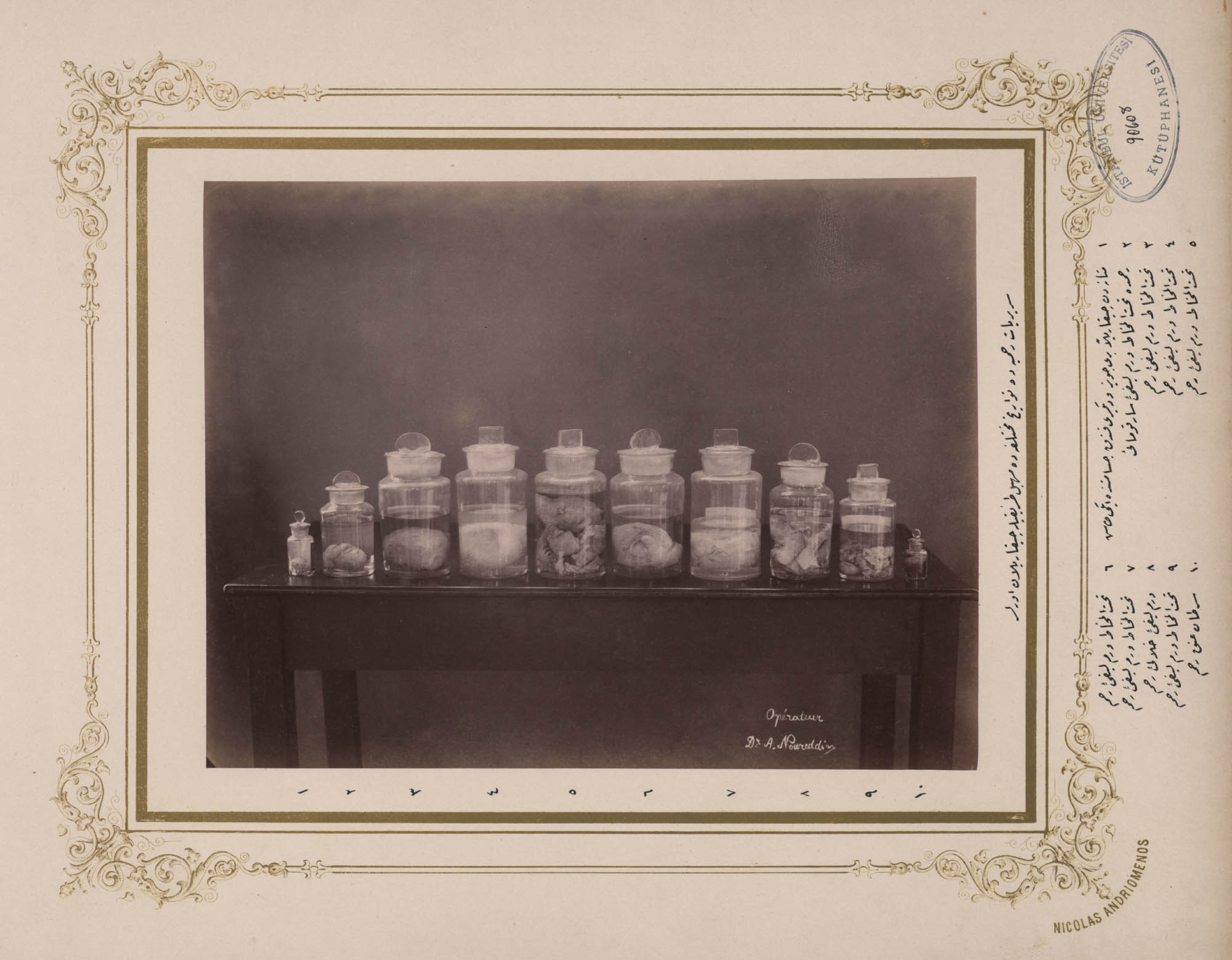

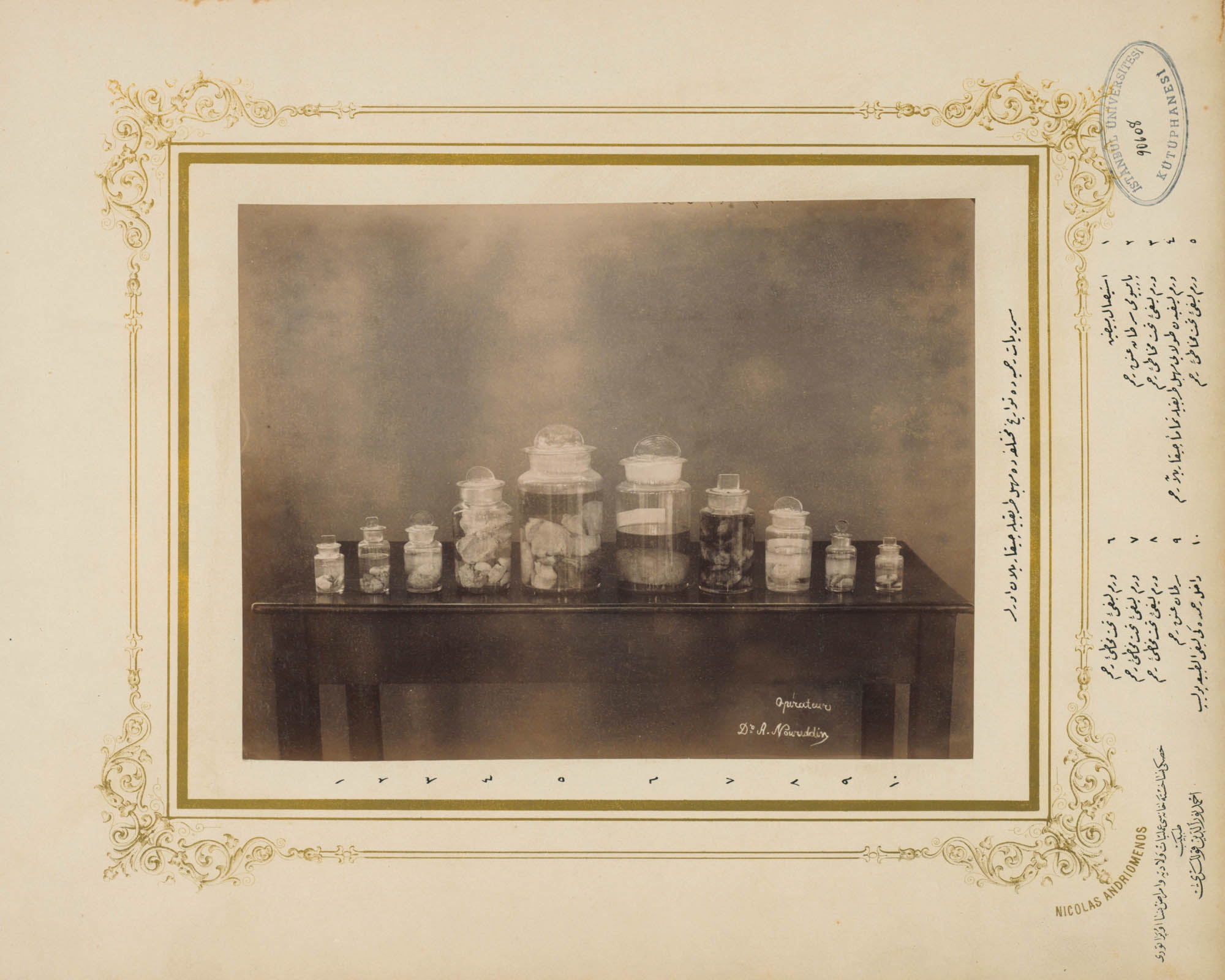

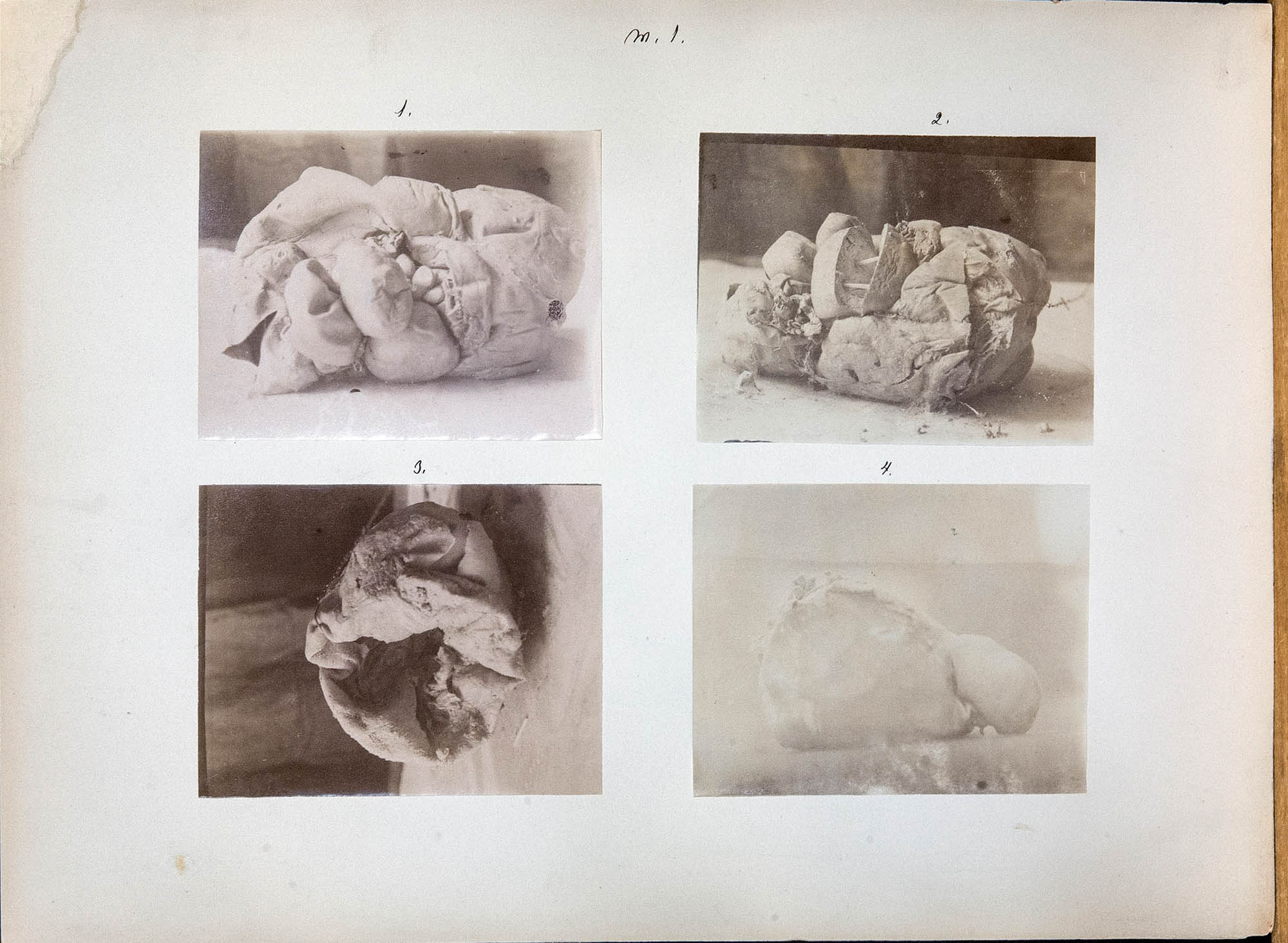

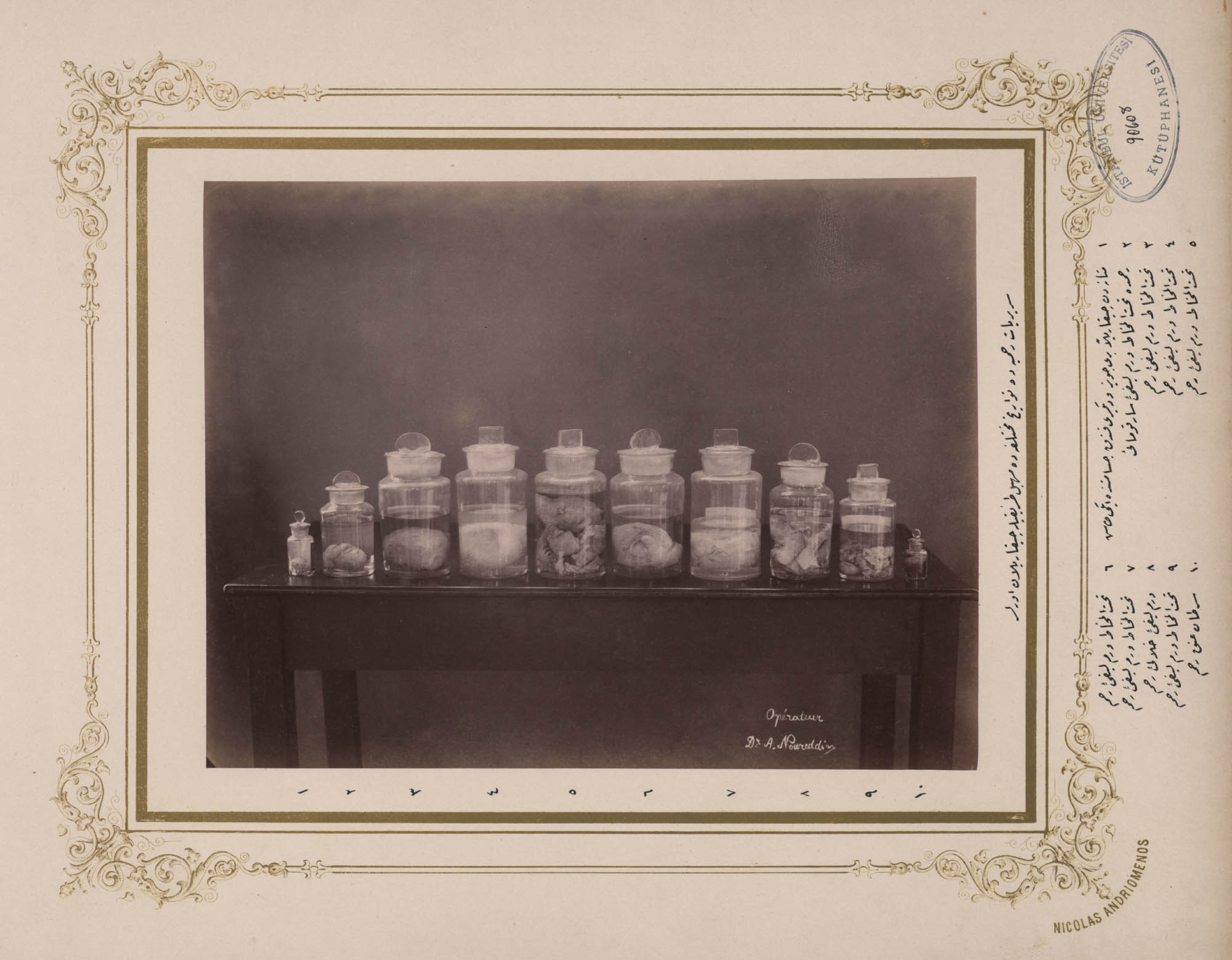

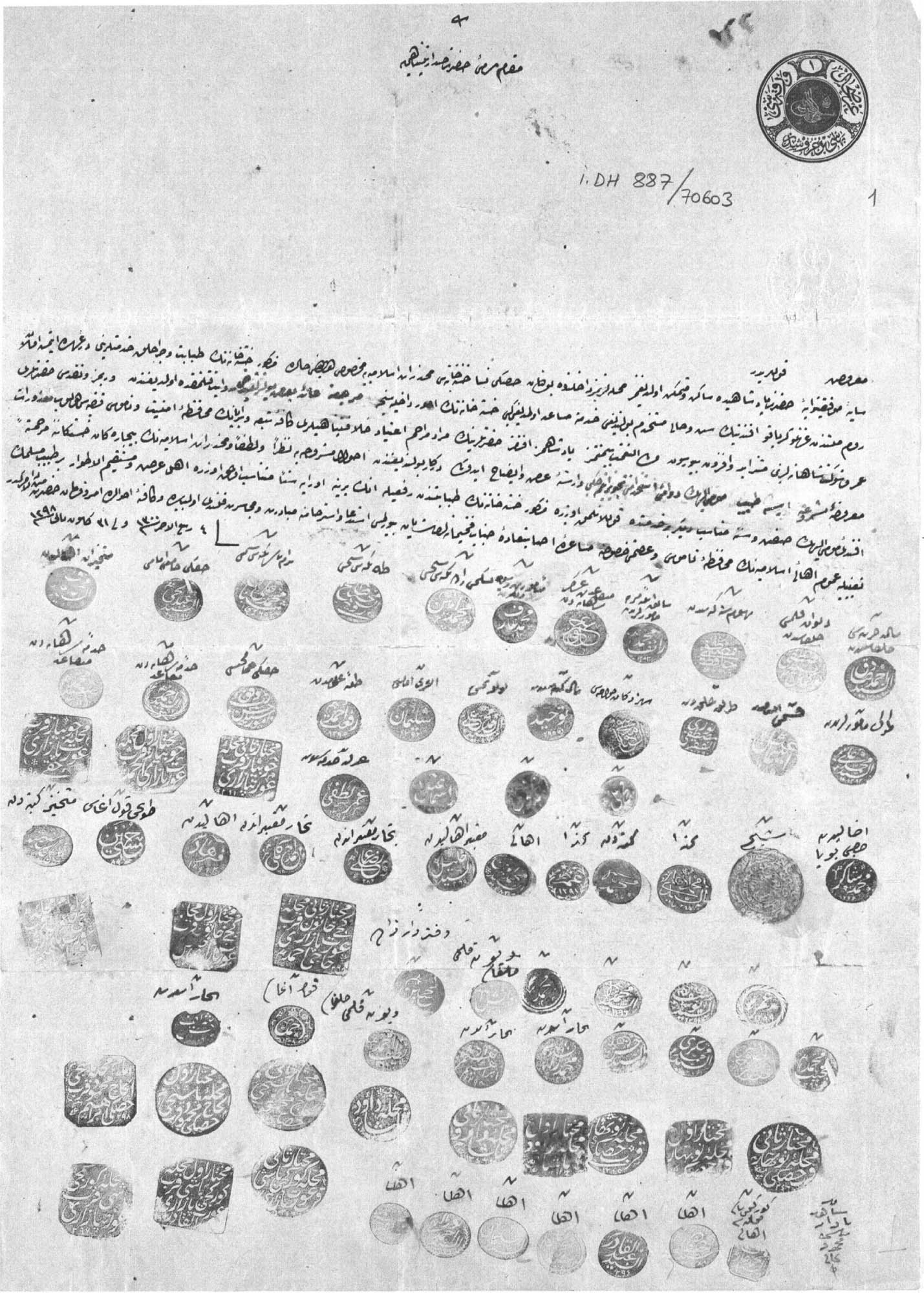

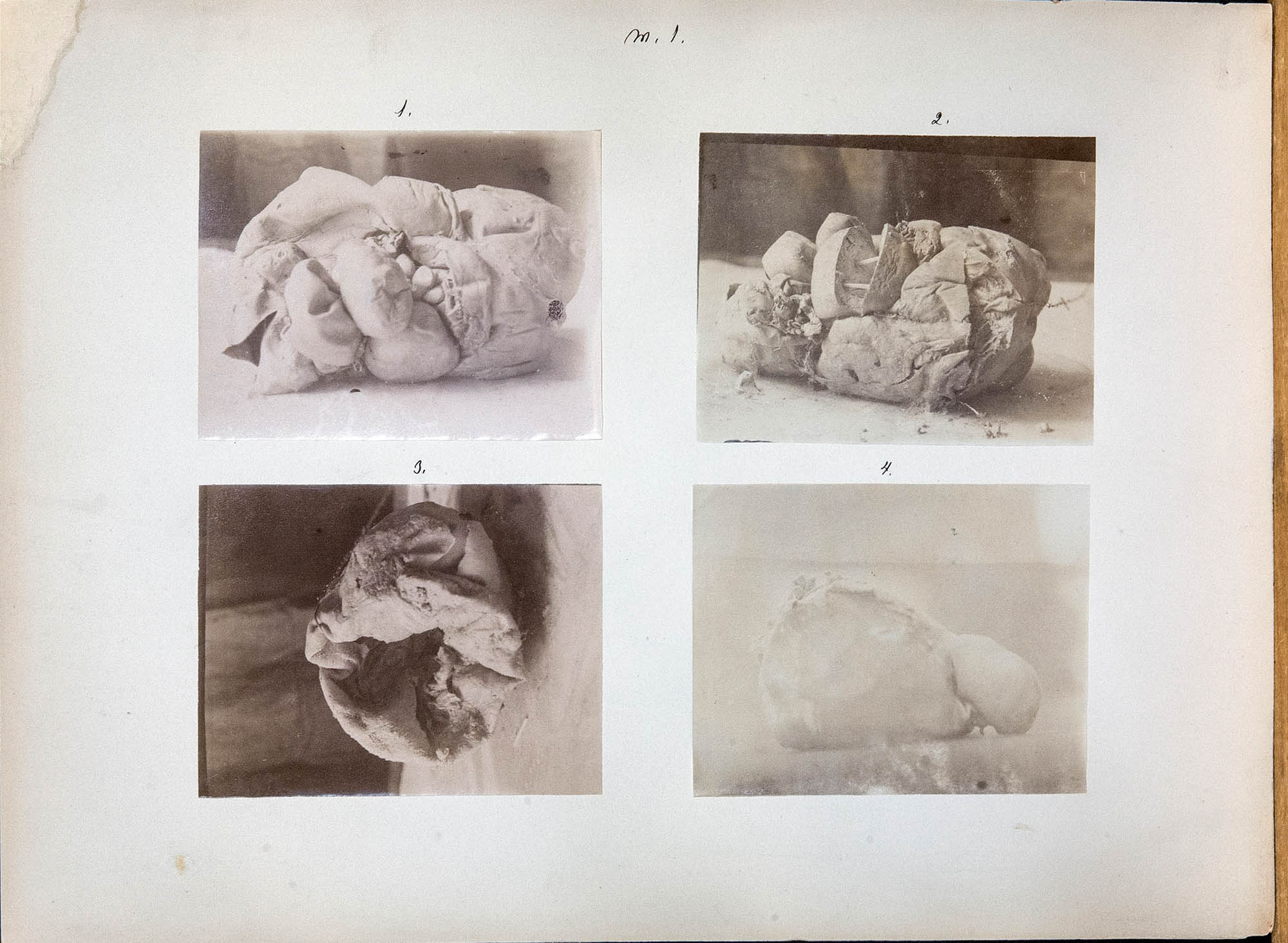

Figure 8 Nicolas Andriomenos.

Tumor lineup 1, ca. 1890–1894.

Image 7, Haseki Women’s

Hospital album formerly part of

Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız Palace

collection. İstanbul Üniversitesi

Nadir Eserler Kütüphanesi

(Istanbul University Library of

Rare Books).Figure 9

Nicolas Andriomenos.

Tumor lineup 1, ca. 1890–1894.

Image 7, Haseki Women’s

Hospital album formerly part of

Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız Palace

collection. İstanbul Üniversitesi

Nadir Eserler Kütüphanesi

(Istanbul University Library of

Rare Books).Figure 9 Nicolas Andriomenos.

Tumor lineup 2, ca. 1890–1894.

Image 8, Haseki Women’s

Hospital album formerly part of

Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız Palace

collection. İstanbul Üniversitesi

Nadir Eserler Kütüphanesi

(Istanbul University Library of

Rare Books).

Nicolas Andriomenos.

Tumor lineup 2, ca. 1890–1894.

Image 8, Haseki Women’s

Hospital album formerly part of

Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız Palace

collection. İstanbul Üniversitesi

Nadir Eserler Kütüphanesi

(Istanbul University Library of

Rare Books).

The final two “group portraits” in the album

might be considered a medical lineup. Jars of tumors

lined up on a table. Each specimen identified by p. 40 type. The first jar, we are told, contains one stone the size of a walnut, the other the size of a hazelnut. The rest are tumors. All were removed

vaginally. That the women from whom these were removed are not photographed

alongside them suggests that the visibility of the surgical scar

is central to the earlier portraits.9 Indeed the bared scar itself is the most

direct site rendering healing visible. That is, we have no reason to doubt

that these patients, too, regained their health, but their scars would not

have been photographable in the same manner. The last page includes

the doctor’s name and title—gynecologist and obstetrician of Haseki

Women’s Hospital and the obligatory term servant (kulları), indicating an

address directly to the sovereign. Captivated by the images, I set out to

understand how and why such an album might have been produced.

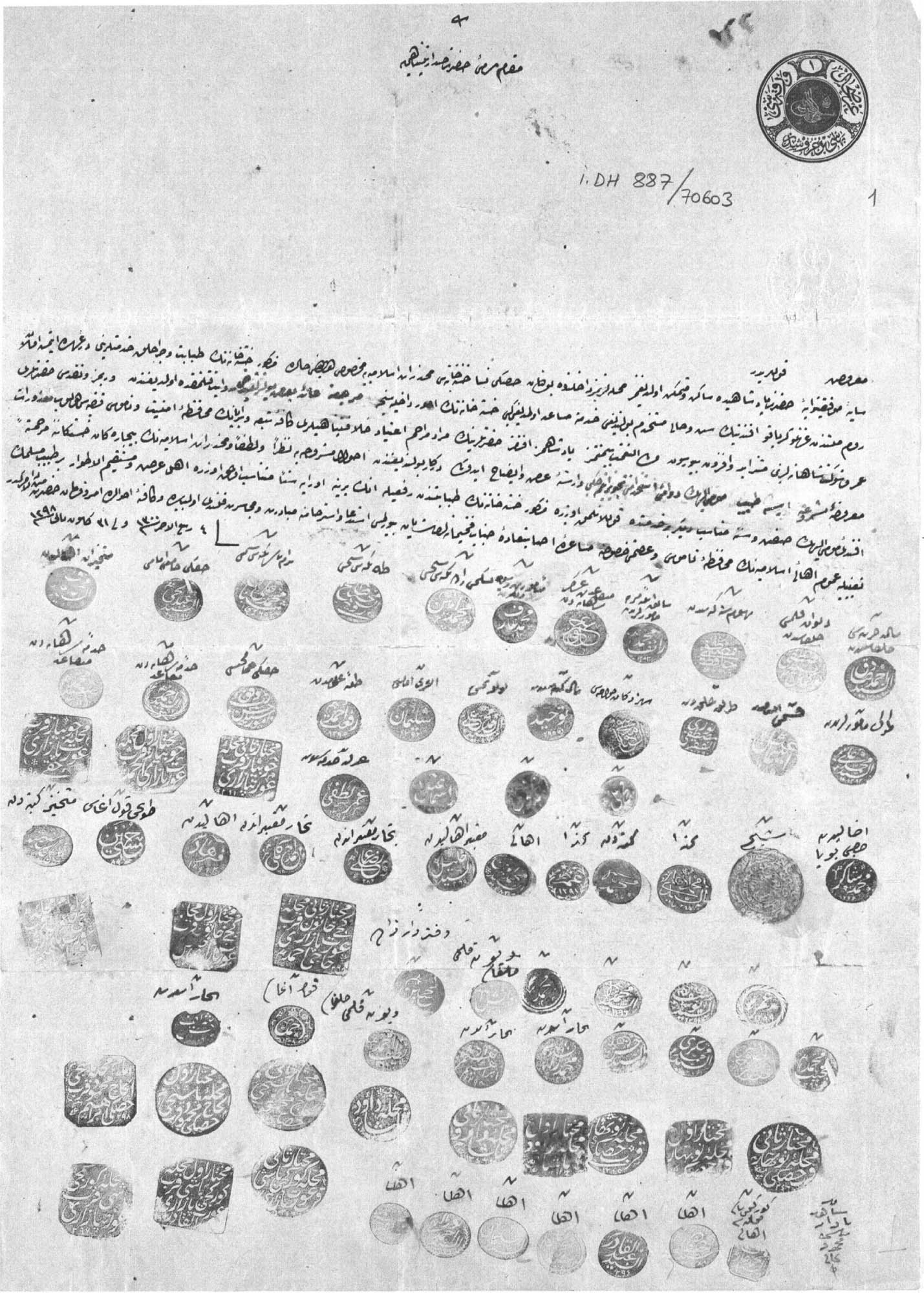

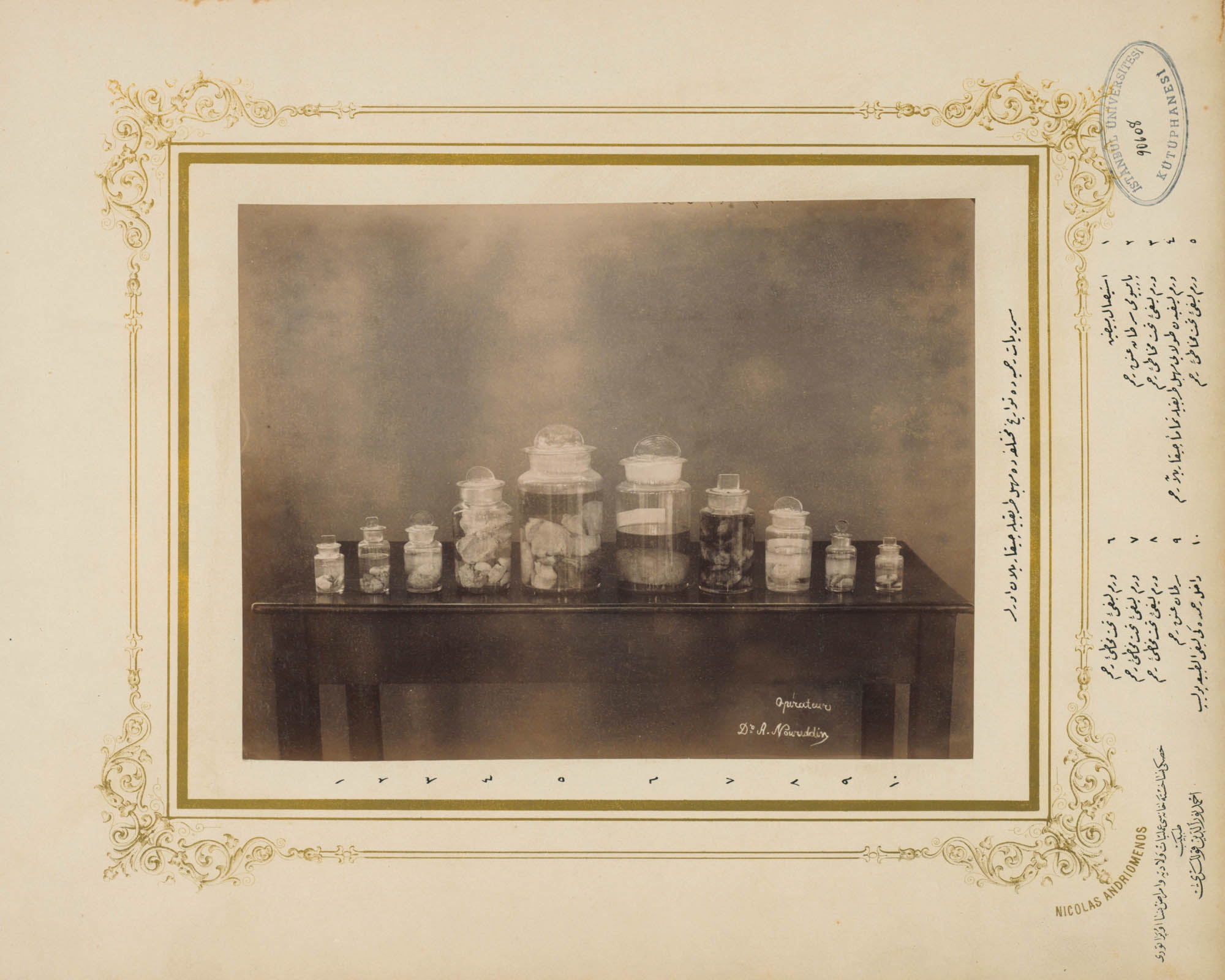

p. 41 Upon searching the Ottoman state archives and studying published

histories of the hospital, I soon encountered Dr. Kiryako, the hospital’s

first dedicated doctor, appointed in 1871. The anxieties around the inappropriate

visibility of the destitute women at Haseki were made exceptionally

public in 1882 when a complaint letter bearing seventy-eight

signatures charged the chief doctor, Kiryako, with mistreating the poor

and looking at covered parts of Muslim women when there was no medical

necessity to do so. The accusers wanted the Greek Ottoman, and

hence non-Muslim, Kiryako replaced with an elderly Muslim doctor.

Kiryako was promptly removed from the position he had held for eleven

years while the authorities investigated the allegations against him.10

After a lengthy investigation lasting several years, the authorities decided p. 42 that the allegations were baseless and that Kiryako, though young, was

an excellent doctor.11 He was reinstated in 1885 and remained the chief

doctor of Haseki Hospital until his death in 1890.12 Significantly, one

example of his medical excellence and dedication given in the documents

clearing his reputation was that he photographed surgery patients

before and after surgeries in accordance with scientific norms and even

paid for this photography himself.13

Figure 10 A complaint letter bearing

seventy-eight signatures accusing

Dr. Kiryako of inappropriate

medical behavior at Haseki

Women’s Hospital, Istanbul, 1882.

Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi

(Prime Ministry Ottoman

Archives).

A complaint letter bearing

seventy-eight signatures accusing

Dr. Kiryako of inappropriate

medical behavior at Haseki

Women’s Hospital, Istanbul, 1882.

Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi

(Prime Ministry Ottoman

Archives).

Nurettin, the surgeon whose signature features

heavily in the Haseki portrait album,

arrived at Haseki Hospital as a junior doctor, the

hospital’s third-ranked doctor, in 1890. This was

the year Kiryako died. Faik Bey had succeeded

Kiryako as chief doctor.14 Nurettin was

appointed as a gynecologist and obstetrician. A

photograph from the period shows him seated

just next to Faik Bey, the new chief doctor.15

I strongly suspect that Nurettin knew of the

accusations brought against Kiryako. According

to Nimet Taşkıran’s history of the hospital,

Nurettin’s father, Basri Bey, a naval doctor, had

been appointed to temporarily direct the hospital

during Kiryako’s suspension.16 Four years after

he arrived, Nurettin left Haseki and appears to

have practiced at another hospital under one

of three Ottoman doctors who had been sent

to France for surgical training. He returned to

Haseki Hospital in 1903 as a general surgeon. He

had an illustrious medical career and commanded

much respect in his day. In 1907 he

became chief doctor at Haseki Hospital and held

this position until his death in 1924.

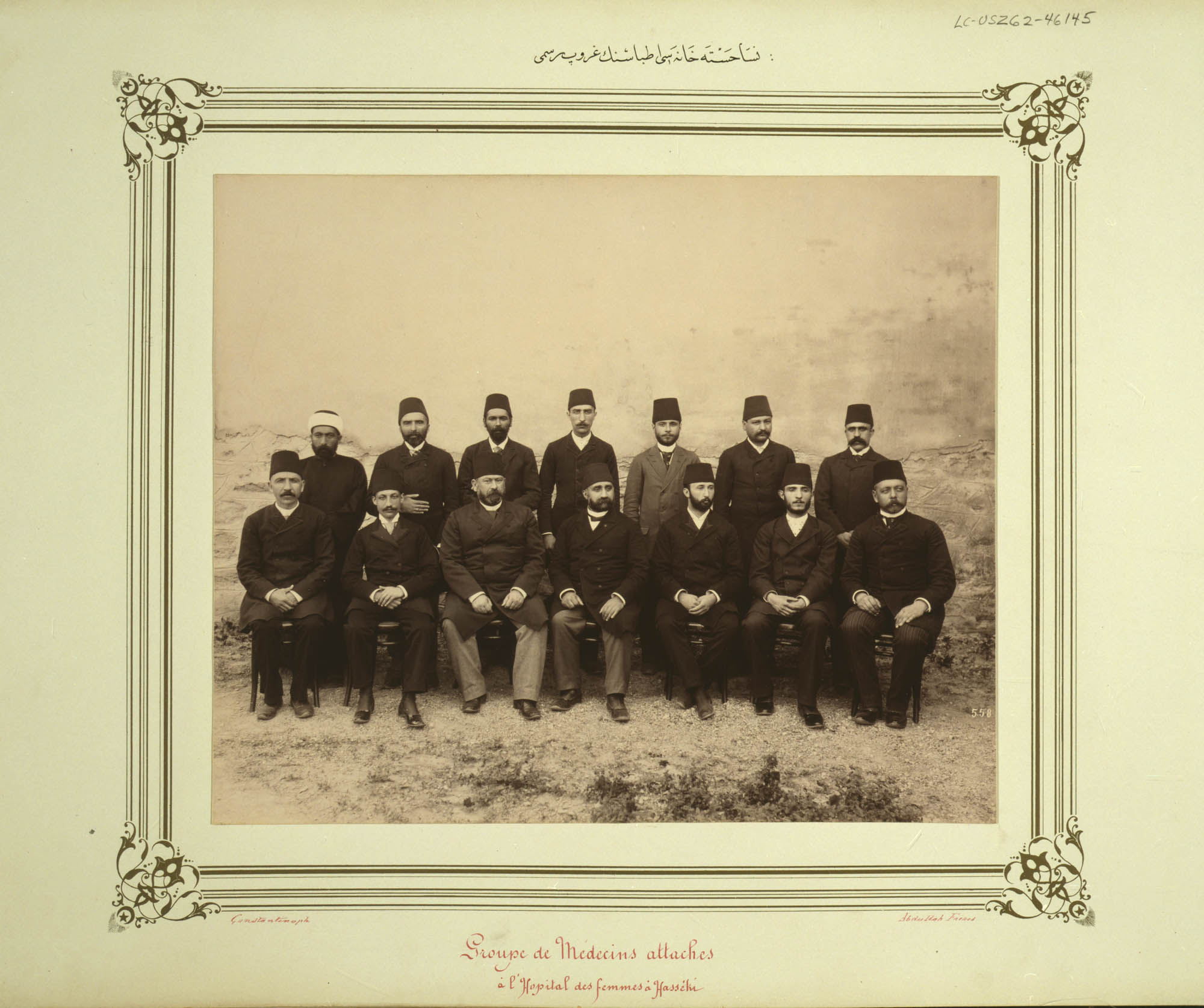

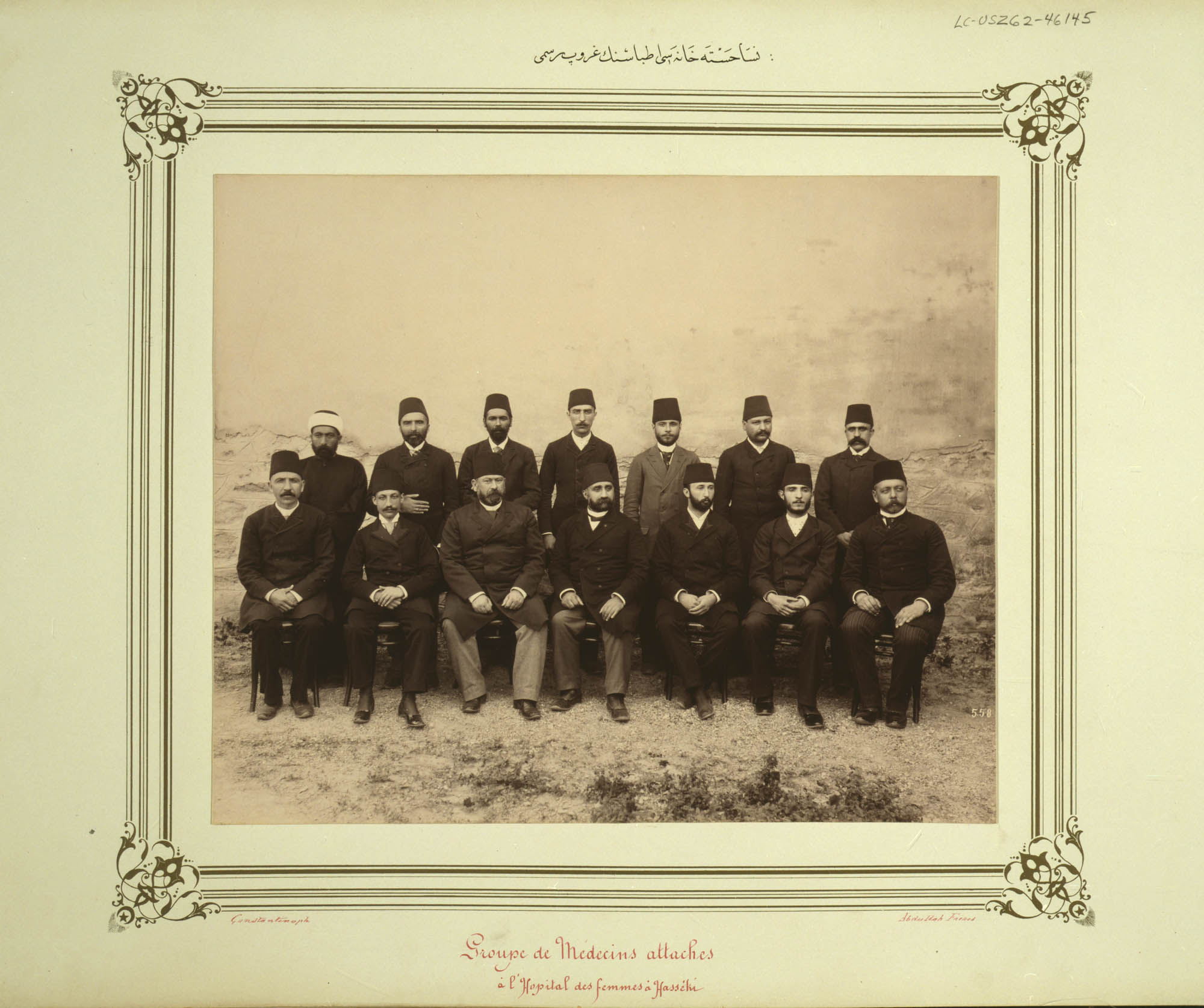

p. 43Figure 11 Abdullah Frères (Abdullah Brothers). Group portrait

of Haseki Women’s Hospital’s

medical staff, ca. 1893. Dr. Ahmed

Nurettin is third from right, front

row. From Hasköy Hospital for

Women, Fountains, Mausoleums,

and Other Buildings and Views,

part of the collection of fifty-one

albums gifted to the Library of

Congress by Abdülhamīd II.

Courtesy Library of Congress. The other protagonist in the story of the Haseki portrait album is

Greek Ottoman photographer Andriomenos, one of the most famous

photographers of the era. Andriomenos had learned photography in the

studio of Kosmi Abdullah, who had his own studio separate from that

of his three brothers, the famous Abdullah Frères who were official

photographers to the sultan. Andriomenos took over Kosmi Abdullah’s

studio in 1879. He was one of the rare photographers who gained access

to the palace and allegedly even gave photography lessons to Sultan

Abdülhamīd’s younger brother, Prince Vahdettin.17

Abdullah Frères (Abdullah Brothers). Group portrait

of Haseki Women’s Hospital’s

medical staff, ca. 1893. Dr. Ahmed

Nurettin is third from right, front

row. From Hasköy Hospital for

Women, Fountains, Mausoleums,

and Other Buildings and Views,

part of the collection of fifty-one

albums gifted to the Library of

Congress by Abdülhamīd II.

Courtesy Library of Congress. The other protagonist in the story of the Haseki portrait album is

Greek Ottoman photographer Andriomenos, one of the most famous

photographers of the era. Andriomenos had learned photography in the

studio of Kosmi Abdullah, who had his own studio separate from that

of his three brothers, the famous Abdullah Frères who were official

photographers to the sultan. Andriomenos took over Kosmi Abdullah’s

studio in 1879. He was one of the rare photographers who gained access

to the palace and allegedly even gave photography lessons to Sultan

Abdülhamīd’s younger brother, Prince Vahdettin.17

I assumed that what I saw in the Haseki portrait album was a visual

medical convention, a genre of medical photography that had later fallen

out of use. I assumed it was a Western medical genre that Dr. Nurettin

had either seen examples of, been told of by other Ottoman doctors who

had been trained abroad, or read about in one of the many foreign medical

journals that circulated in the empire.18 However, a broad survey of

medical historians, archivists, librarians, and medical museum curators

not only in Istanbul but all over North America and Europe yielded no

similar portraits.19 All consulted were surprised by the images and told

me they had never seen anything like it. And by “like it” they meant a

portrait of a live human with something that had been removed from

them, an image in which the once internal was on display. They were

reminded of images of corpses with an organ removed but could not

think of one where the subject of the portrait was still alive, let alone “a

picture of health” or “a landscape of healing,” as Nurettin described the

patients in the Haseki portrait album.

Rather than an Ottoman application of a Western or universal medical

photography, I now understand the Haseki portrait album as a visual

negotiation at a moment when a genre of medical photography had not

yet stabilized.20 New genres do not emerge fully formed but rather must

be crafted from borrowing, reshaping, and repurposing existing forms.

In the absence of an accepted method or style, Nurettin and photographer

Andriomenos drew from the practices and codes

of the existing genres of medical illustration and studio

portraiture.21 However, I arrived at this conclusion

only after appreciating the ways in which they must

have collaborated.

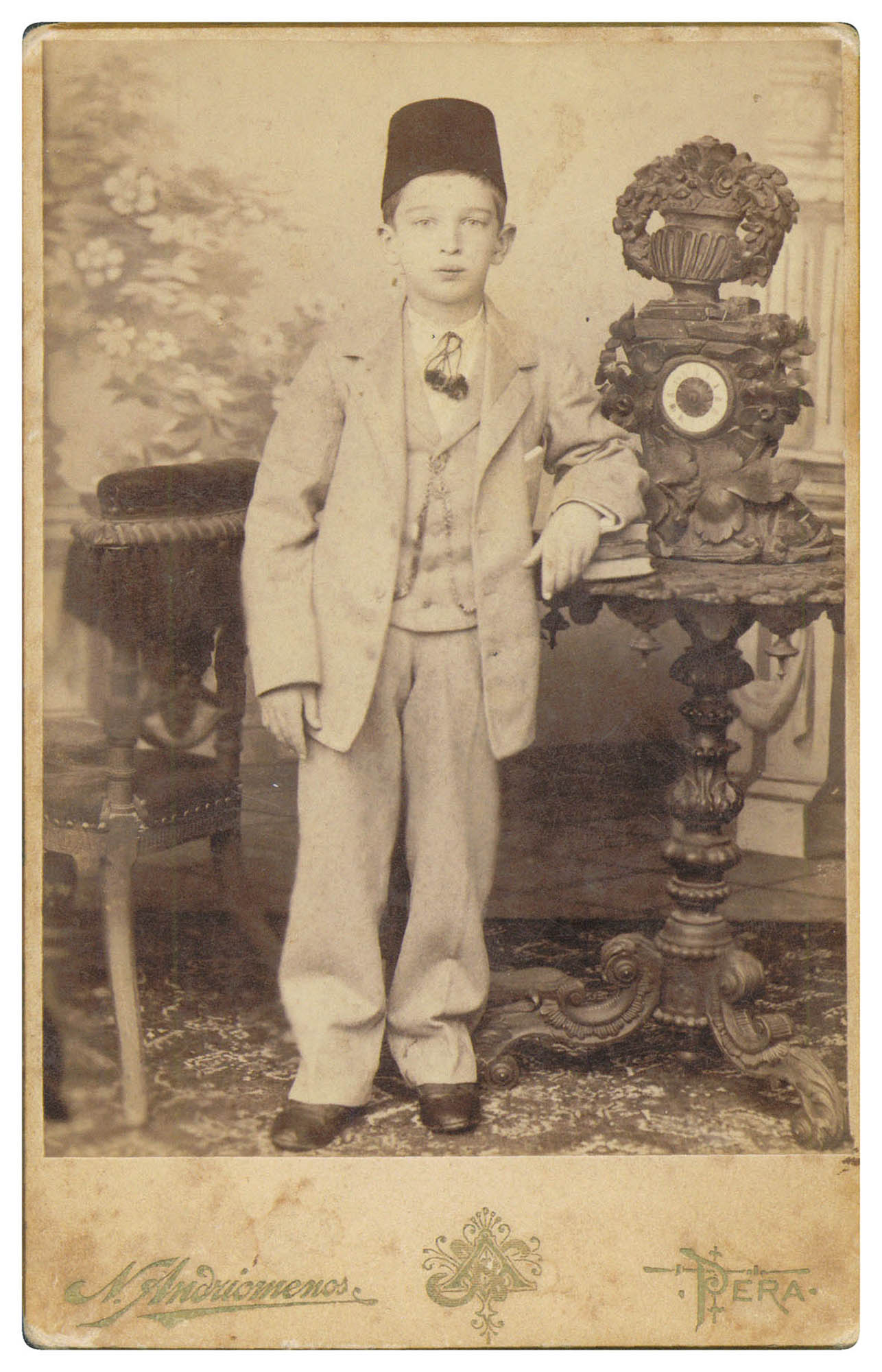

Figure 12 Nicolas Andriomenos. Studio

portrait of a couple, ca. 1879–

1912. The same carpet appears

in photographs from the Haseki

Women’s Hospital album

formerly part of Abdülhamīd II’s

Yıldız Palace collection. Courtesy

Gülderen Bölük.

Nicolas Andriomenos. Studio

portrait of a couple, ca. 1879–

1912. The same carpet appears

in photographs from the Haseki

Women’s Hospital album

formerly part of Abdülhamīd II’s

Yıldız Palace collection. Courtesy

Gülderen Bölük.

My first question was where the portraits of the

patients were taken, and so I searched private photography

collections for portraits taken by Andriomenos

in his studio. First, I recognized the carpet that appeared

in many of the portraits.22 Then one of the collectors

spotted the table in the Haseki portraits. Sure enough, p. 44 here was proof that the carpet and the table in the portraits were from Andriomenos’s studio. That the photographer would come to the hospital

with all this equipment was hard to imagine, but less so than imagining

the women and their tumors being transported to the photographer’s studio.

But then I found a photograph that confirmed the women and their

tumors must have been transported to the studio. In one portrait from the

album, we clearly see the same floor design as in another Andriomenos

studio portrait. Horse-drawn trams began operating in Istanbul in the

1870s and the route from Haseki Hospital to Andriomenos’s Beyazıt studio

was on one of the earliest routes. The distance between the studio and

the hospital was only 1.9 kilometers.23

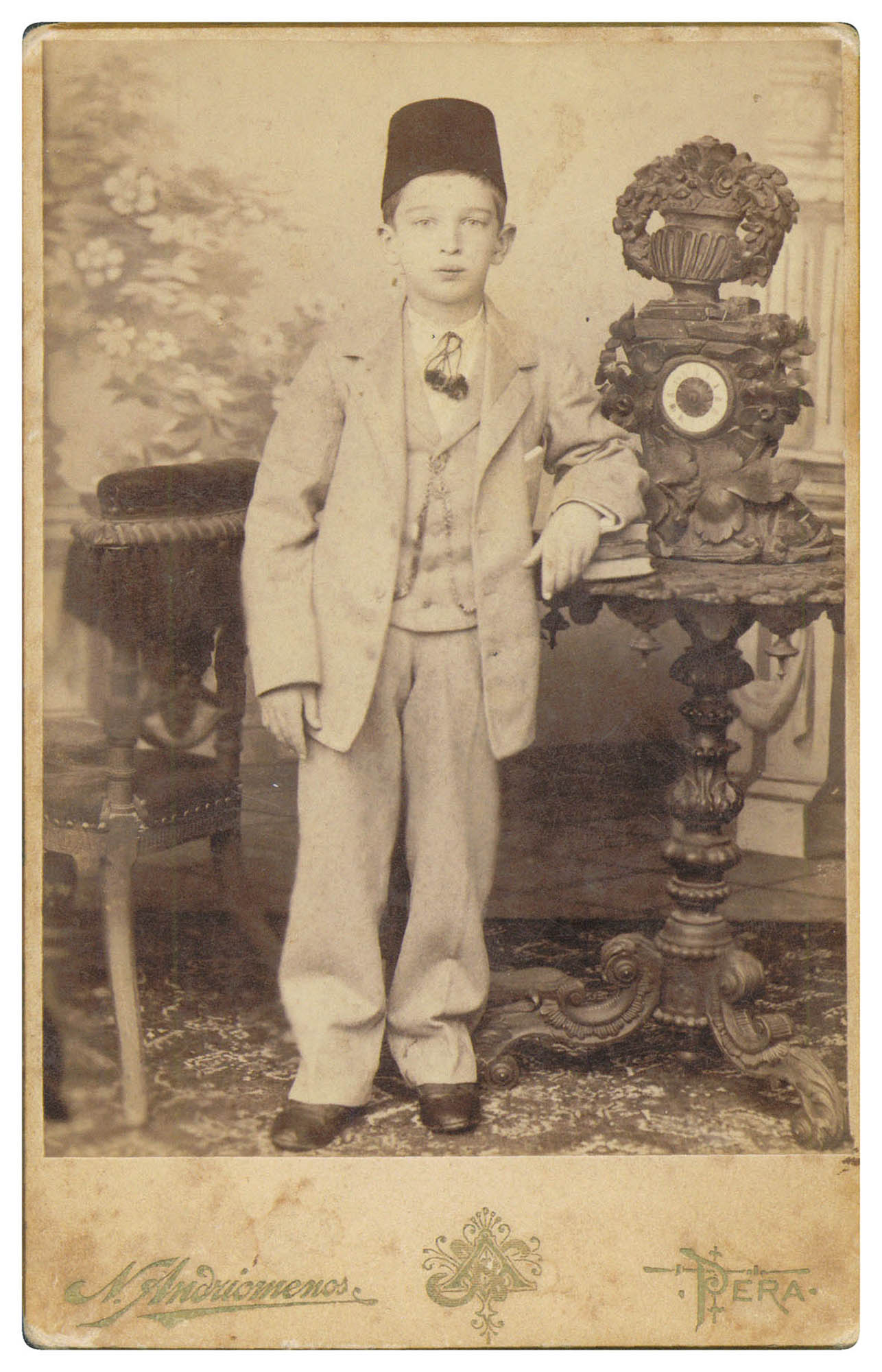

Figure 13 Nicolas Andriomenos.

Studio portrait of a boy, ca.

1879–1912. The same decorative

table appears in photographs

from the Haseki Women’s

Hospital album formerly part of

Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız Palace collection.

Courtesy Adem Köse.Figure 14

Nicolas Andriomenos.

Studio portrait of a boy, ca.

1879–1912. The same decorative

table appears in photographs

from the Haseki Women’s

Hospital album formerly part of

Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız Palace collection.

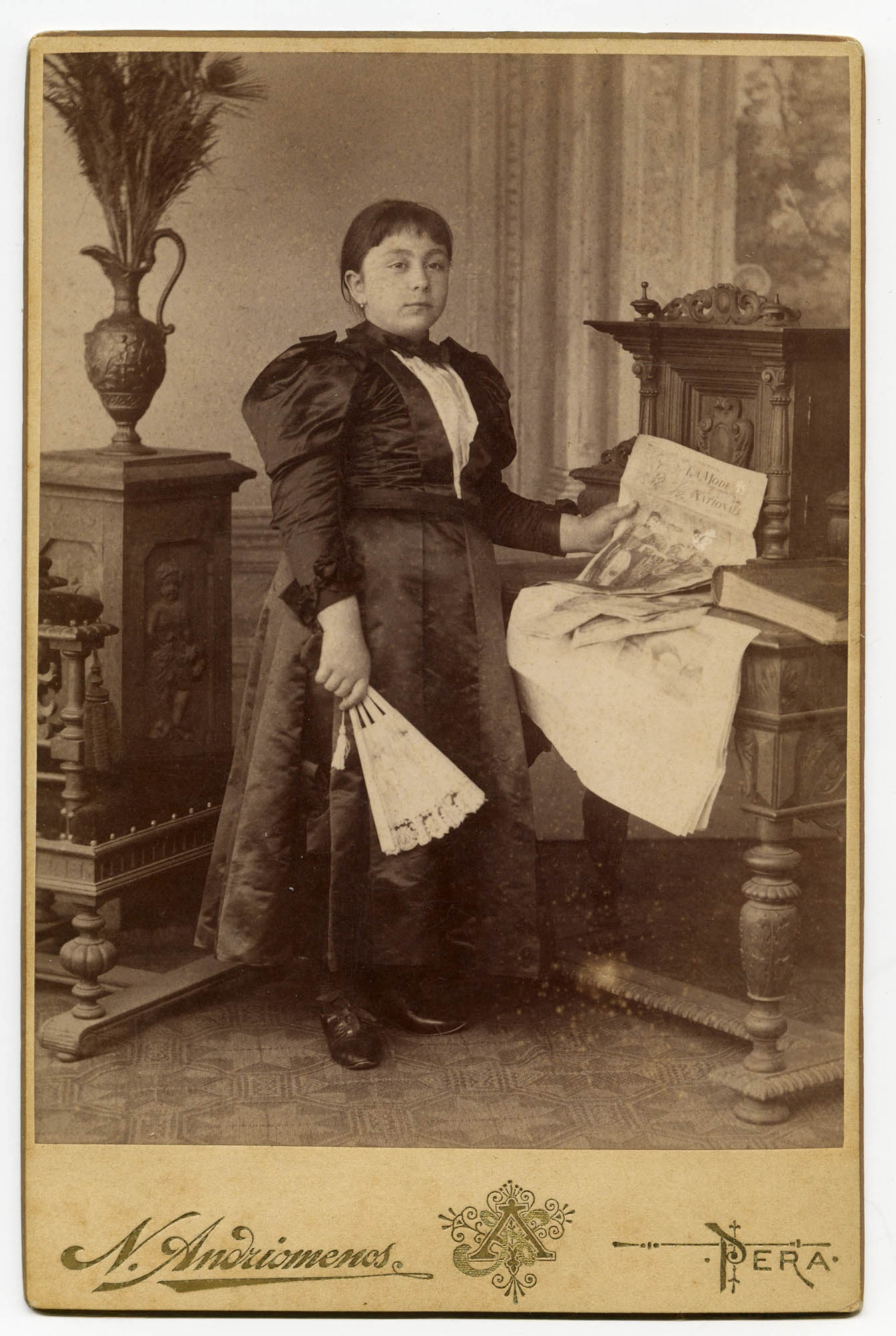

Courtesy Adem Köse.Figure 14 Nicolas Andriomenos.

Studio portrait of a woman, ca.

1879–1912. The same floor

appears in the portrait of Misli

Hatun, image 6 of Haseki

Women’s Hospital album formerly

part of Abdülhamīd II’s

Yıldız Palace collection. Courtesy

Gülderen Bölük.

Nicolas Andriomenos.

Studio portrait of a woman, ca.

1879–1912. The same floor

appears in the portrait of Misli

Hatun, image 6 of Haseki

Women’s Hospital album formerly

part of Abdülhamīd II’s

Yıldız Palace collection. Courtesy

Gülderen Bölük.

Nimet Taşkıran’s history of Haseki Hospital (published in 1972) states

that there was an identical album to the one in Abdülhamīd’s collection

in Yıldız Palace, and in the summer of 2014 I finally located a second

album in a private collection.24 However, it was not identical. The crimson

velvet cover is similar (if significantly more worn), and all of the

images in the sultan’s album are also in this album, but the handwriting

is much less ornate, and the captions include no biographical information

about the women. Instead, only the medical terms for the surgeries

and specific descriptors of the tumors are given, suggesting to me that

this album was prepared by the doctor for himself or another medical p. 45 colleague. Should he want biographical information, Nurettin would be

able to consult the hospitals records for the patients. Moreover, the second

album has seven photographs that were not included in the sultan’s

album. These additional images mostly seem to have been taken at the

hospital itself, though two photographs feature the carpet and decorative

table from the studio. We see the hospital’s bare floor and a stove, but the

women are not uniformly dressed. One image shows two specimen jars.

In another, two women have placed a hand on the same specimen jar, as

if they shared a tumor. Perhaps the two shadows visible behind the woman

in the seventh photograph belonged to the doctor and the photographer.

Figure 17 Nicolas Andriomenos. Woman with two bell jars containing

tumors, ca. 1893–1907.

Image 1, Haseki Women’s Hospital

album, private collection. Photograph not included in the

Haseki portrait album sent to

Yıldız Palace. Courtesy Ömer M. Koç Collection.Figure 18

Nicolas Andriomenos. Woman with two bell jars containing

tumors, ca. 1893–1907.

Image 1, Haseki Women’s Hospital

album, private collection. Photograph not included in the

Haseki portrait album sent to

Yıldız Palace. Courtesy Ömer M. Koç Collection.Figure 18 Nicolas Andriomenos, ca.

1893–1907. Image 2, Haseki

Women’s Hospital album, private

collection. Photograph not included in the

Haseki portrait album sent to

Yıldız Palace. Courtesy Ömer M.

Koç Collection.Figure 19

Nicolas Andriomenos, ca.

1893–1907. Image 2, Haseki

Women’s Hospital album, private

collection. Photograph not included in the

Haseki portrait album sent to

Yıldız Palace. Courtesy Ömer M.

Koç Collection.Figure 19 Nicolas Andriomenos. Two

patients and a single tumor, ca.

1893–1907. Image 3, Haseki

Women’s Hospital album, private

collection. Photograph not included in the

Haseki portrait album sent to

Yıldız Palace. Courtesy Ömer M.

Koç Collection.Figure 20

Nicolas Andriomenos. Two

patients and a single tumor, ca.

1893–1907. Image 3, Haseki

Women’s Hospital album, private

collection. Photograph not included in the

Haseki portrait album sent to

Yıldız Palace. Courtesy Ömer M.

Koç Collection.Figure 20 Nicolas Andriomenos, ca.

1893–1907. Image 4, Haseki

Women’s Hospital album, private

collection. Photograph not included in the

Haseki portrait album sent to

Yıldız Palace. Courtesy Ömer M.

Koç Collection.Figure 21

Nicolas Andriomenos, ca.

1893–1907. Image 4, Haseki

Women’s Hospital album, private

collection. Photograph not included in the

Haseki portrait album sent to

Yıldız Palace. Courtesy Ömer M.

Koç Collection.Figure 21 Nicolas Andriomenos, ca.

1893–1907. Image 7, Haseki

Women’s Hospital album, private

collection. Photograph not included in the

Haseki portrait album sent to

Yıldız Palace. Courtesy Ömer M.

Koç Collection.Figure 22

Nicolas Andriomenos, ca.

1893–1907. Image 7, Haseki

Women’s Hospital album, private

collection. Photograph not included in the

Haseki portrait album sent to

Yıldız Palace. Courtesy Ömer M.

Koç Collection.Figure 22 Nicolas Andriomenos, ca.

1893–1907. Image 8, Haseki

Women’s Hospital album, private

collection. One of two photographs

in the album seemingly photographed in Andriomenos’s studio. Photograph not included in the

Haseki portrait album sent to

Yıldız Palace. Courtesy Ömer M. Koç Collection.

Nicolas Andriomenos, ca.

1893–1907. Image 8, Haseki

Women’s Hospital album, private

collection. One of two photographs

in the album seemingly photographed in Andriomenos’s studio. Photograph not included in the

Haseki portrait album sent to

Yıldız Palace. Courtesy Ömer M. Koç Collection.

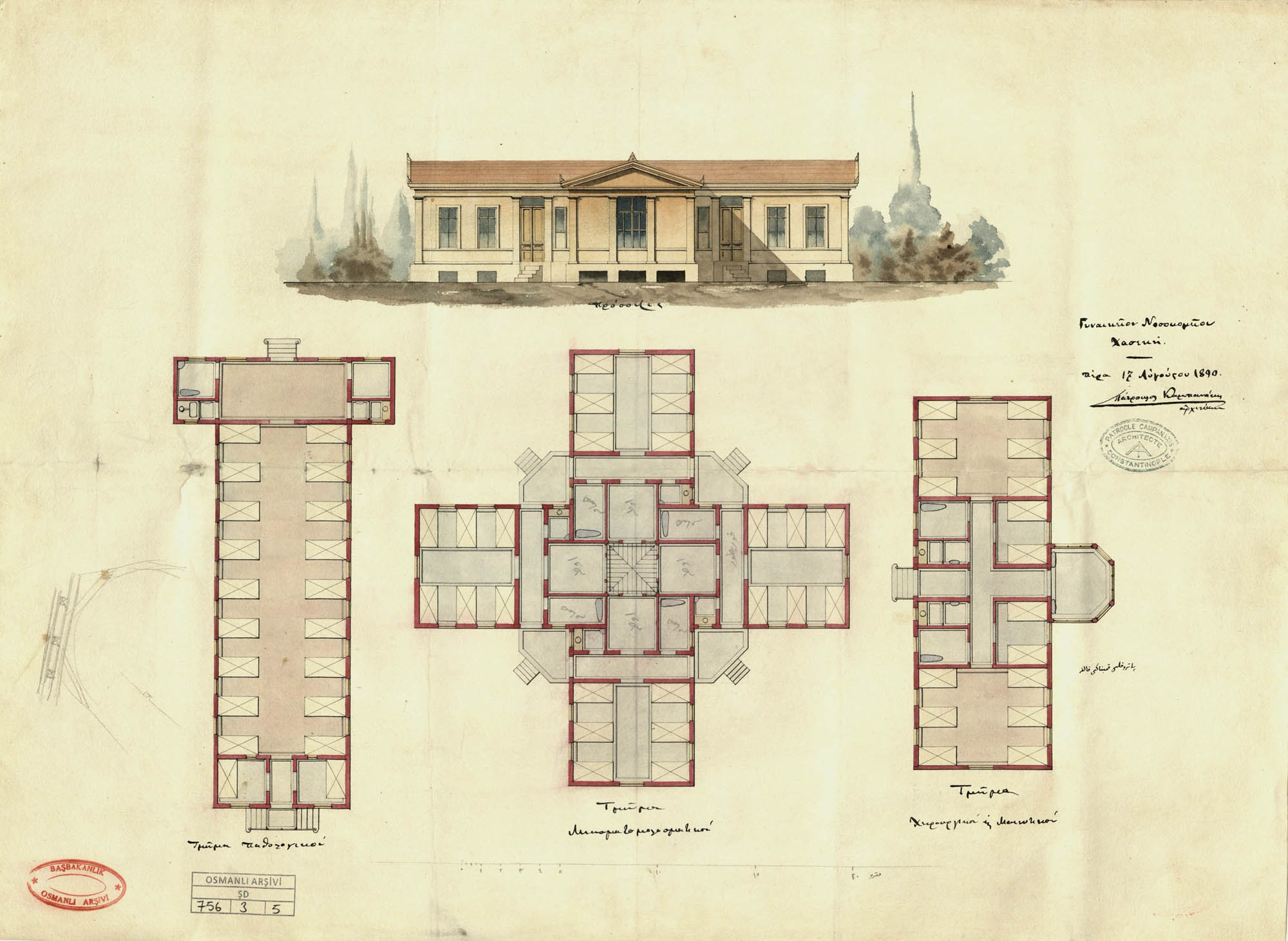

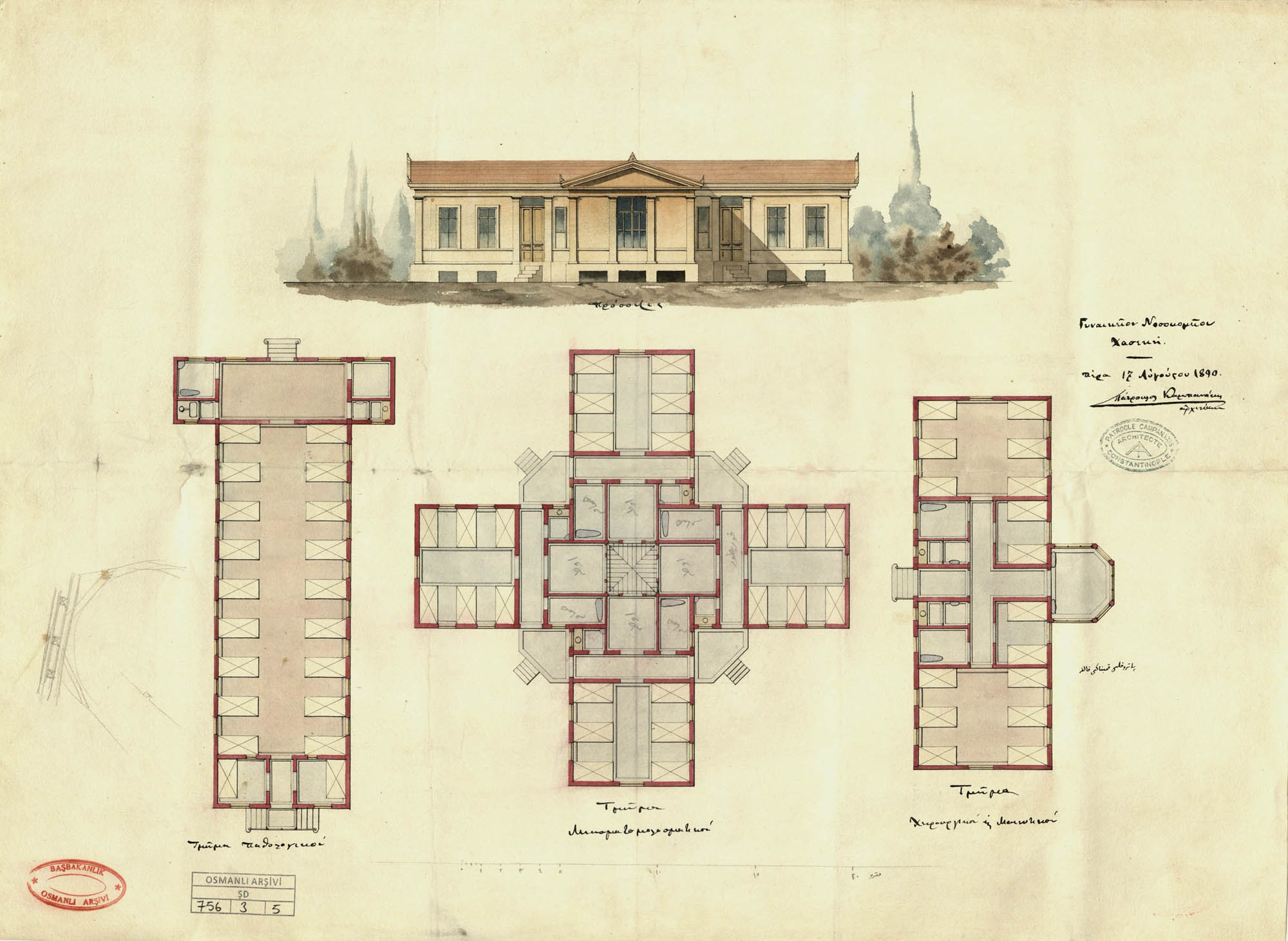

Next I turned to the architectural record for clues and found that the

early 1890s was a time of big changes for Haseki Hospital. The main

building—the stone house that had been repurposed for patients (Taş

konak)—was torn down in 1890, and the hospital made due in barracks

for a few years before the pavilions that allowed for segregation of

patients according to disease were opened in 1893. I had assumed that

the photographs included in the second album were taken in the hospital

rather than in Andriomenos’s studio. The stone house was a dark build-p. 47 ing with small windows, and prior to the invention of flash it would have

been difficult to make these images in such an interior. The new pavilions

were designed to let in maximum light. When I looked closely at the

images, I saw that what I had taken for a shadow is not a shadow at all but

rather a reflection. The light is coming from a window behind the photographer

and the stove would have been placed close to an interior

rather than external wall. Hence, these must be the reflections of the

doctor and photographer on an interior window giving on to a dark

corridor. When I found the architectural drawings that Patrocle Kampanaki

made for the pavilions in a document dated 1891, the plans showed precisely

such corridors with windows onto the postoperation patient rooms

in the surgery pavilion.25

Figure 23 Patrocle Kampanaki.

Architectural plan for Haseki

Women’s Hospital pavilions, 1891.

The plan shows corridors with

windows separating patient

wards from the operating rooms.

Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi

(Prime Ministry Ottoman

Archives).Figure 24

Patrocle Kampanaki.

Architectural plan for Haseki

Women’s Hospital pavilions, 1891.

The plan shows corridors with

windows separating patient

wards from the operating rooms.

Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi

(Prime Ministry Ottoman

Archives).Figure 24 Nicolas Andriomenos.

Photograph showing nurses

standing in a window-lined corridor

of the surgery building at

Haseki Women’s Hospital,

Istanbul, ca. 1914–1924. Courtesy

Refhan Bilol.

Nicolas Andriomenos.

Photograph showing nurses

standing in a window-lined corridor

of the surgery building at

Haseki Women’s Hospital,

Istanbul, ca. 1914–1924. Courtesy

Refhan Bilol.

After much searching I found Dr. Nurettin’s granddaughter (born in

1924, the year he died), and after many teas together she remembered

where she had placed an album of Haseki Hospital, most likely created

during World War I.26 Both the architectural details and floor tiles in the

photographs confirmed my earlier hunches that the additional images

in this second album, now in the collection of Ömer M. Koç, were

taken in the hospital’s new pavilions opened in 1893 rather than in

Andriomenos’s studio.27

The existence of a second album with significant differences from the

album sent to Yıldız Palace proves that the palace album (full of “pictures

of health” that visualize care and captions that underscore healing

and recovery) was deliberately constructed for the sultan. The Haseki

portrait album is undated but was likely produced between the time of

Nurettin’s arrival at the hospital in 1890 and his departure in 1894—

perhaps before the new pavilions opened in 1893, when it became

possible to photograph patients in the hospital.

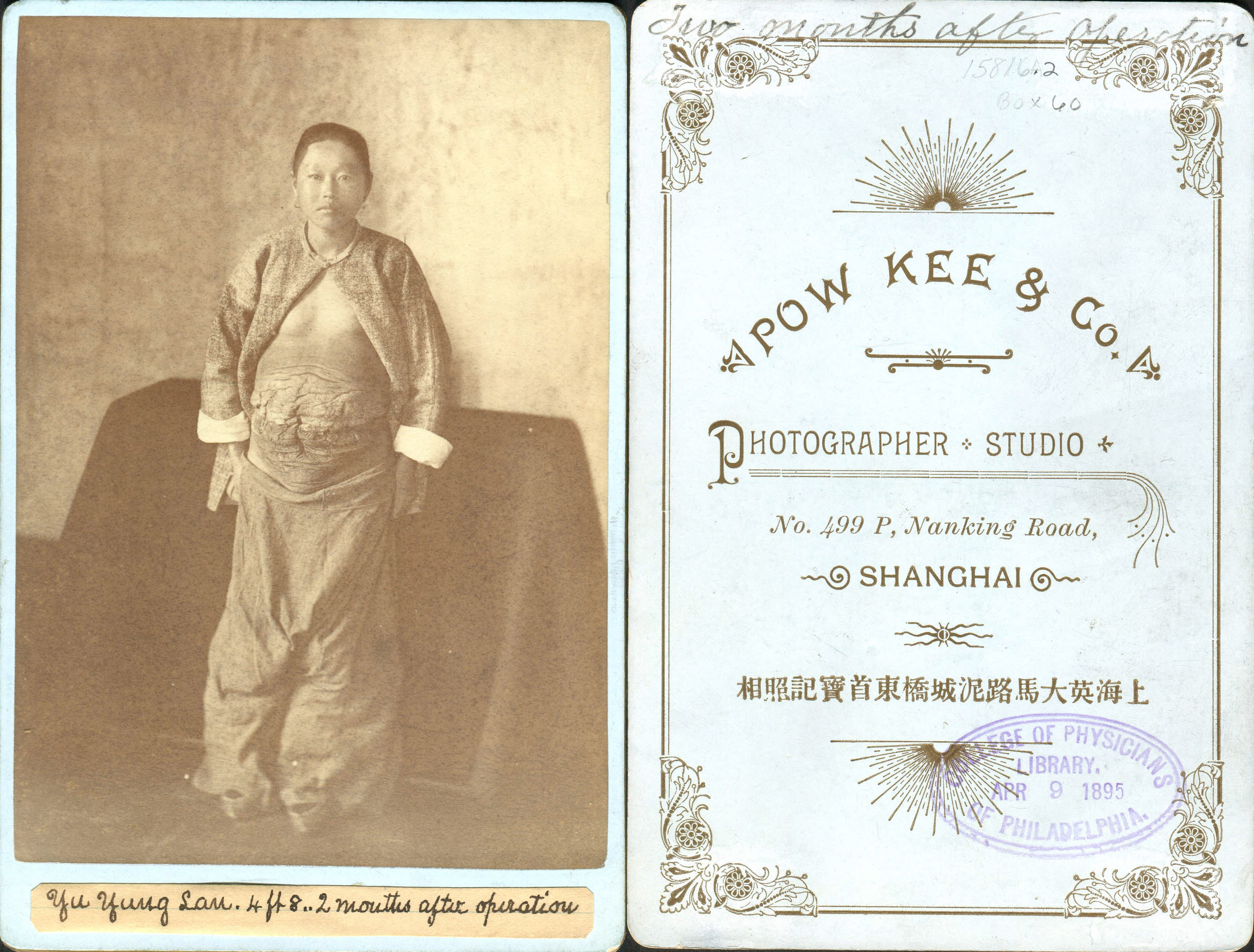

I kept searching through many photographs of tumors worldwide and

eventually found two examples of comparable photographs taken within

a few years of the Haseki portraits, one from Russia and the other from

China. The Russian “publication”—in which the images are merely glued

to the pages—was prepared by surgeon Ivan Kashkarov in St. Petersburg p. 48 and shows some of the celiotomies he performed from 1889 to 1892.

However, in contrast to the Haseki portraits, the postsurgery women

and the tumors are photographed separately. One patient is photographed holding a presurgery photograph of herself. The scrapbook-like

publication seems intended mostly for other surgeons. In his preface,

Kashkarov writes,

Side by side with good photographs I have had to put poor ones,

because I thought that, much like poor photographs of familiar sites

may evoke in our mind more elevated and lovely images, just in the

same manner some of my lower quality photos are capable to

evoke, by the law of ideational association, good images in the

brains of those who truly love their craft. Another aim of this publication

is instructional, and that could be deduced from my drawings

by any specialist. My last aim is the desire to invite a range of

more artistic images than my photographs, most of which were

taken with rather inexpensive equipment.28

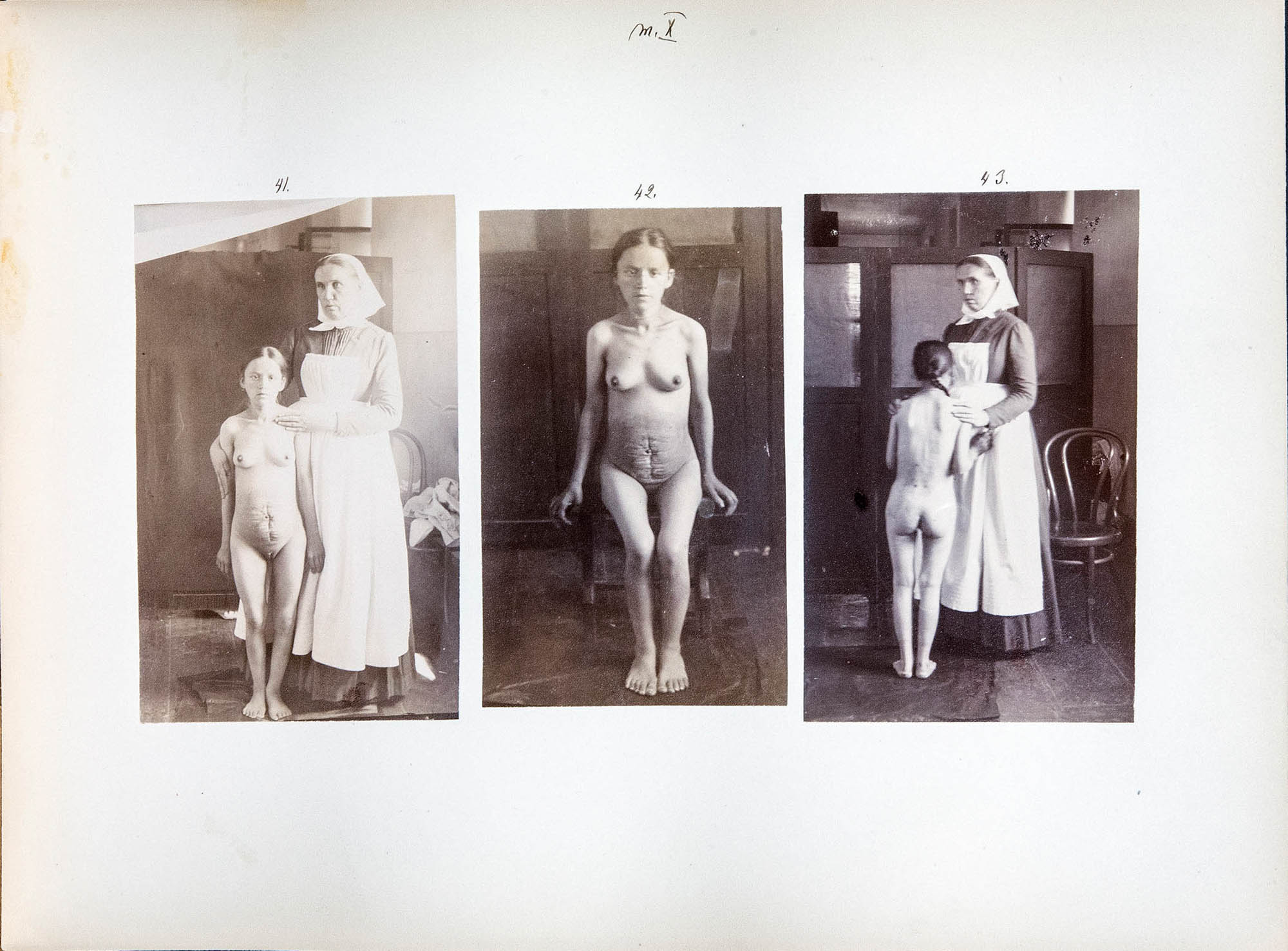

Figure 25 From Ivan Kashkarov,

Klinicheskiya besedy o chrevosecheniyakh

pri boleznyakh

zhenskikh polovykh organov

(Photographic album of laparotomies

in diseases of female

sexual organs; 1893). Courtesy

U.S. National Library of Medicine.Figure 26

From Ivan Kashkarov,

Klinicheskiya besedy o chrevosecheniyakh

pri boleznyakh

zhenskikh polovykh organov

(Photographic album of laparotomies

in diseases of female

sexual organs; 1893). Courtesy

U.S. National Library of Medicine.Figure 26 From Ivan Kashkarov,

Klinicheskiya besedy o chrevosecheniyakh

pri boleznyakh

zhenskikh polovykh organov

(Photographic album of laparotomies

in diseases of female

sexual organs; 1893). Courtesy

U.S. National Library of Medicine.

From Ivan Kashkarov,

Klinicheskiya besedy o chrevosecheniyakh

pri boleznyakh

zhenskikh polovykh organov

(Photographic album of laparotomies

in diseases of female

sexual organs; 1893). Courtesy

U.S. National Library of Medicine.

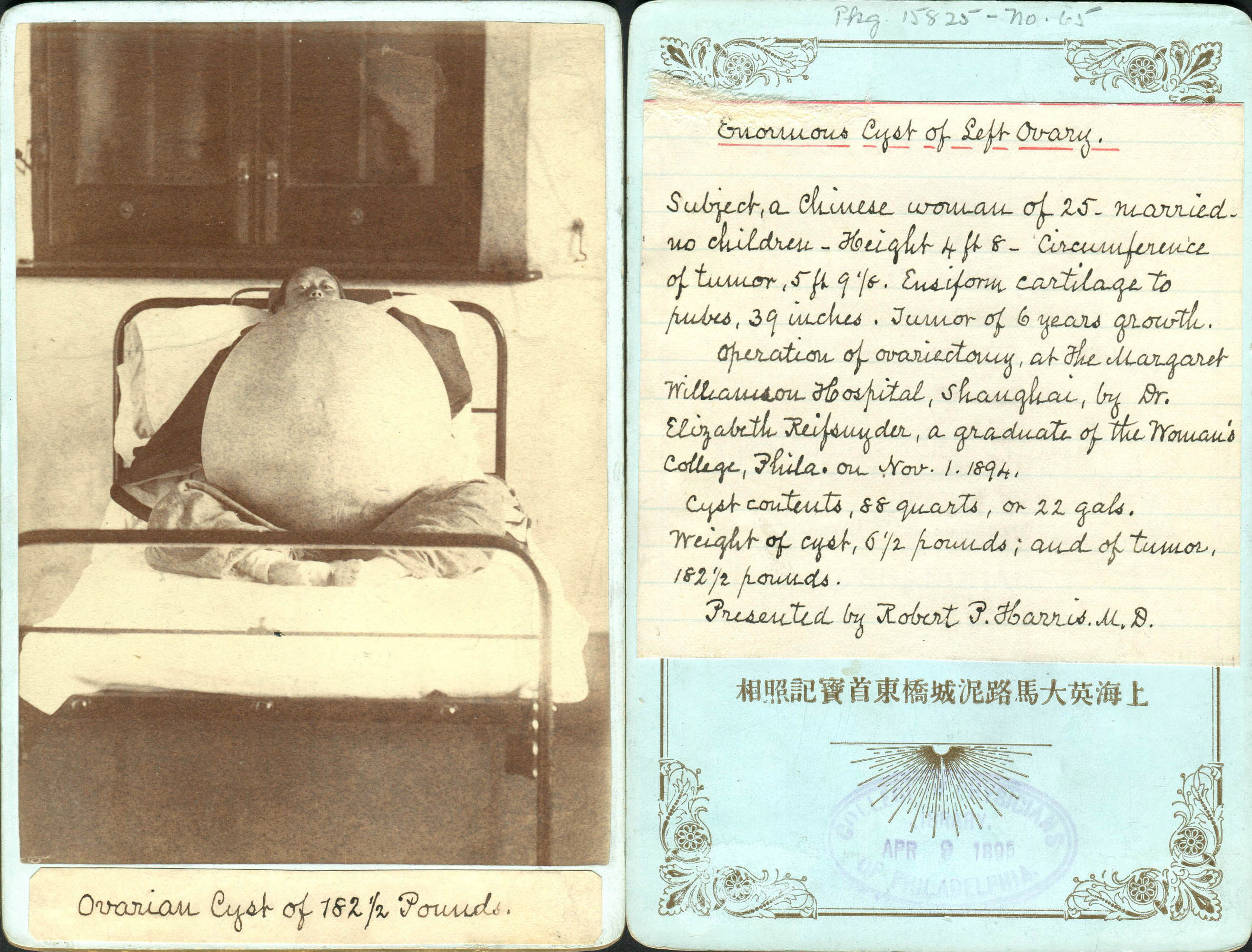

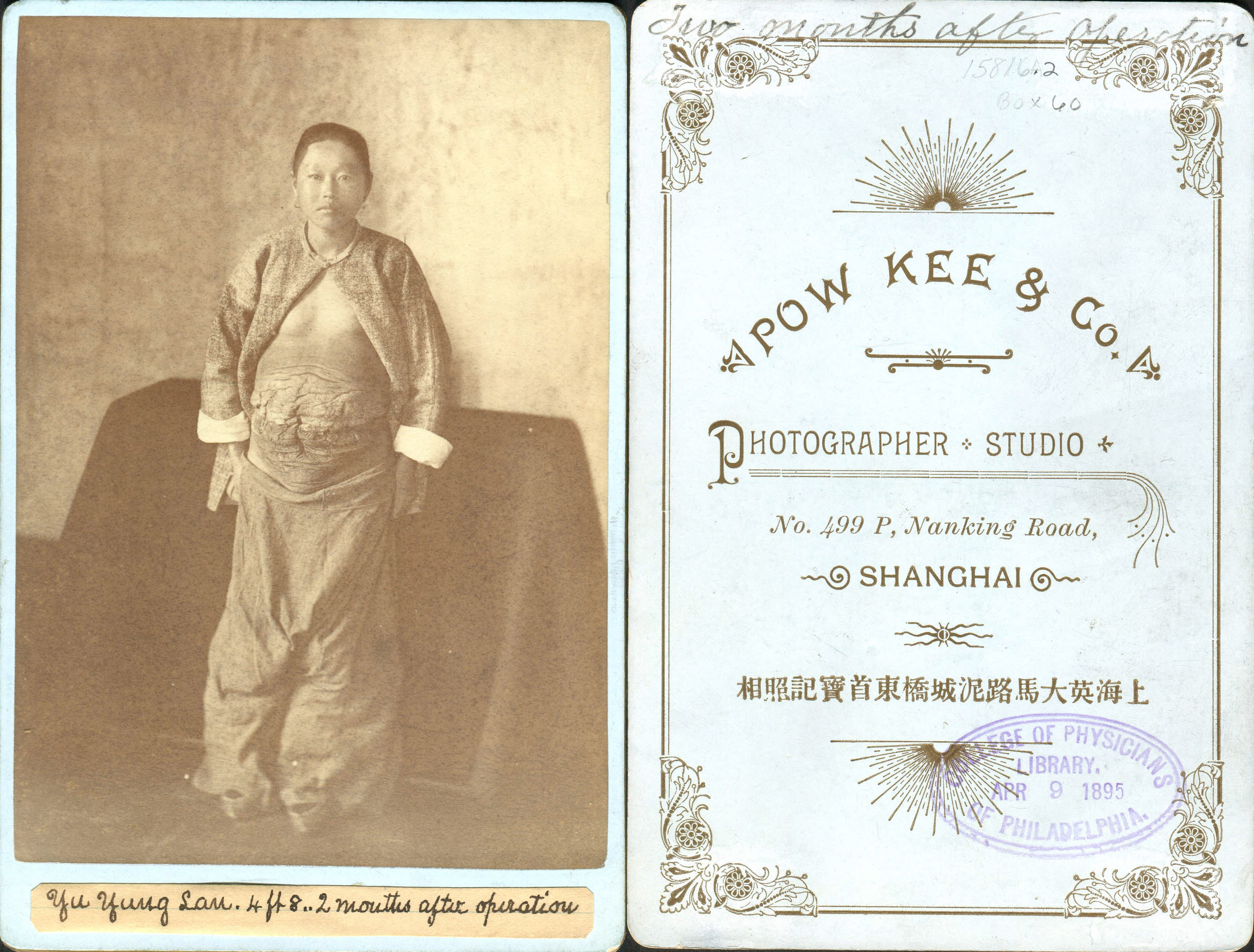

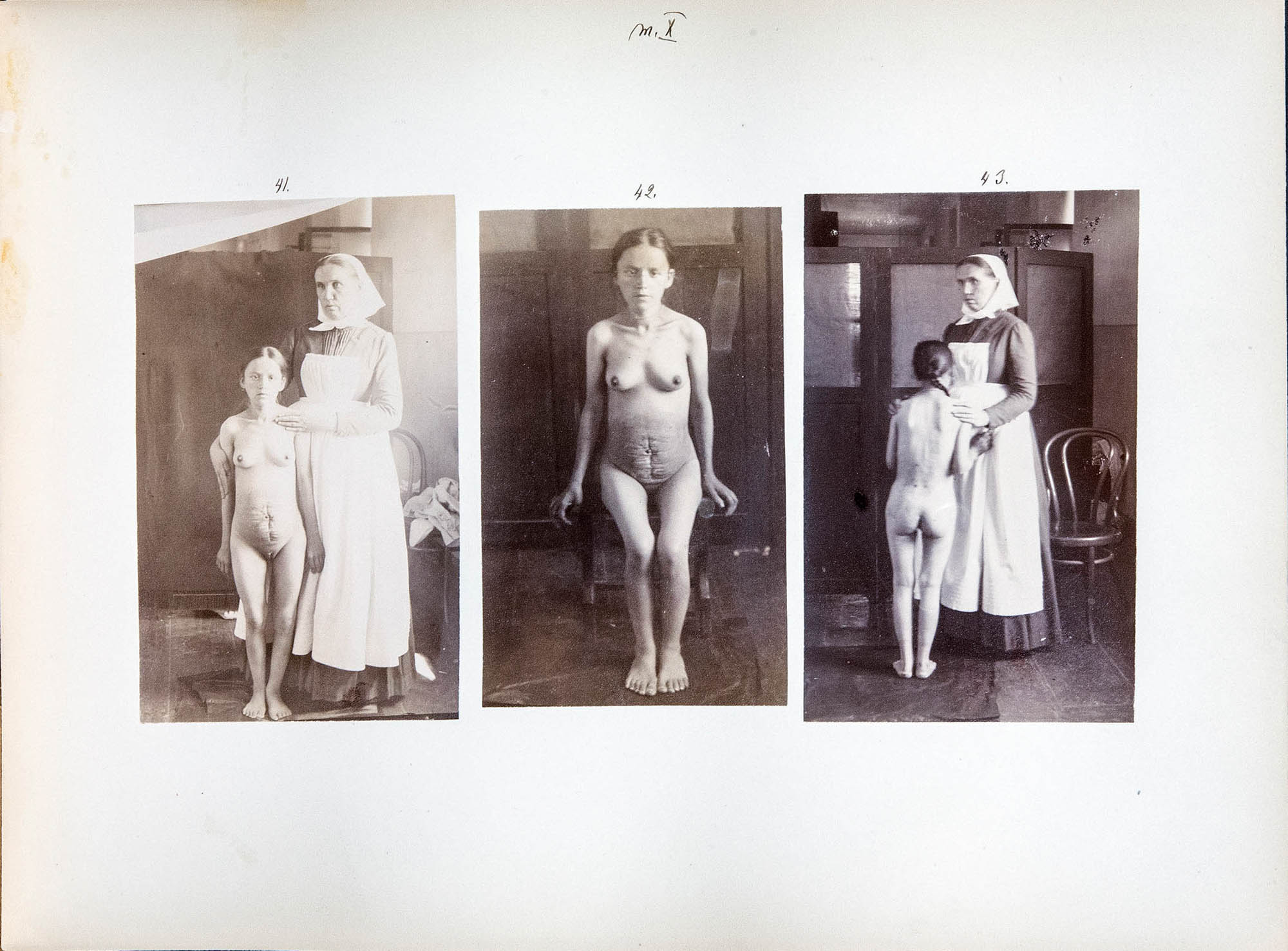

The Chinese example comes from Shanghai. Elizabeth Reifsnyder, a

doctor and medical missionary at the Margaret Williamson Hospital in

Shanghai, sent three images to Philadelphia.29 The first shows Yu Yung

Lan (a twenty-five-year-old married Chinese woman) before her ovariectomy

in 1894. Another photograph shows her two months after the operation.

From a letter giving an annual report of sorts written to a doctor in

Philadelphia on March 31, 1892, we learn that Reifsnyder had been working

in a somewhat rural hospital for some time, but that the Chinese were

still wary of Western doctors. Reifsnyder informs her medical community

back home,

Last year was a special one for us from the fact that two Chinese

women with large ovarian tumors had the courage to be operated

upon, and that in the face of all the opposition they met with from

their friends, relatives and acquaintances. One of the patients is a

Shanghai woman. I will forward her picture by this mail. Thinking p. 49 she might die, before coming to the hospital she had a photographer

come to her house and take her picture. A few days ago she

brought her picture, taken recently, four months after her operation.

I send both copies. Her tumor weighed thirty-seven pounds.30

The Shanghai woman mentioned in this letter is not Yu Yung Lan, whose

tumor weighed 182.5 pounds and was removed in 1894. But the tradition

of photographing patients before and after surgery (started by the patient

mentioned in the 1892 letter) must have continued. Reifsnyder’s letter

assigns a great deal of agency to the Chinese patient for the decisions to

undergo surgery and to be photographed before and after.31

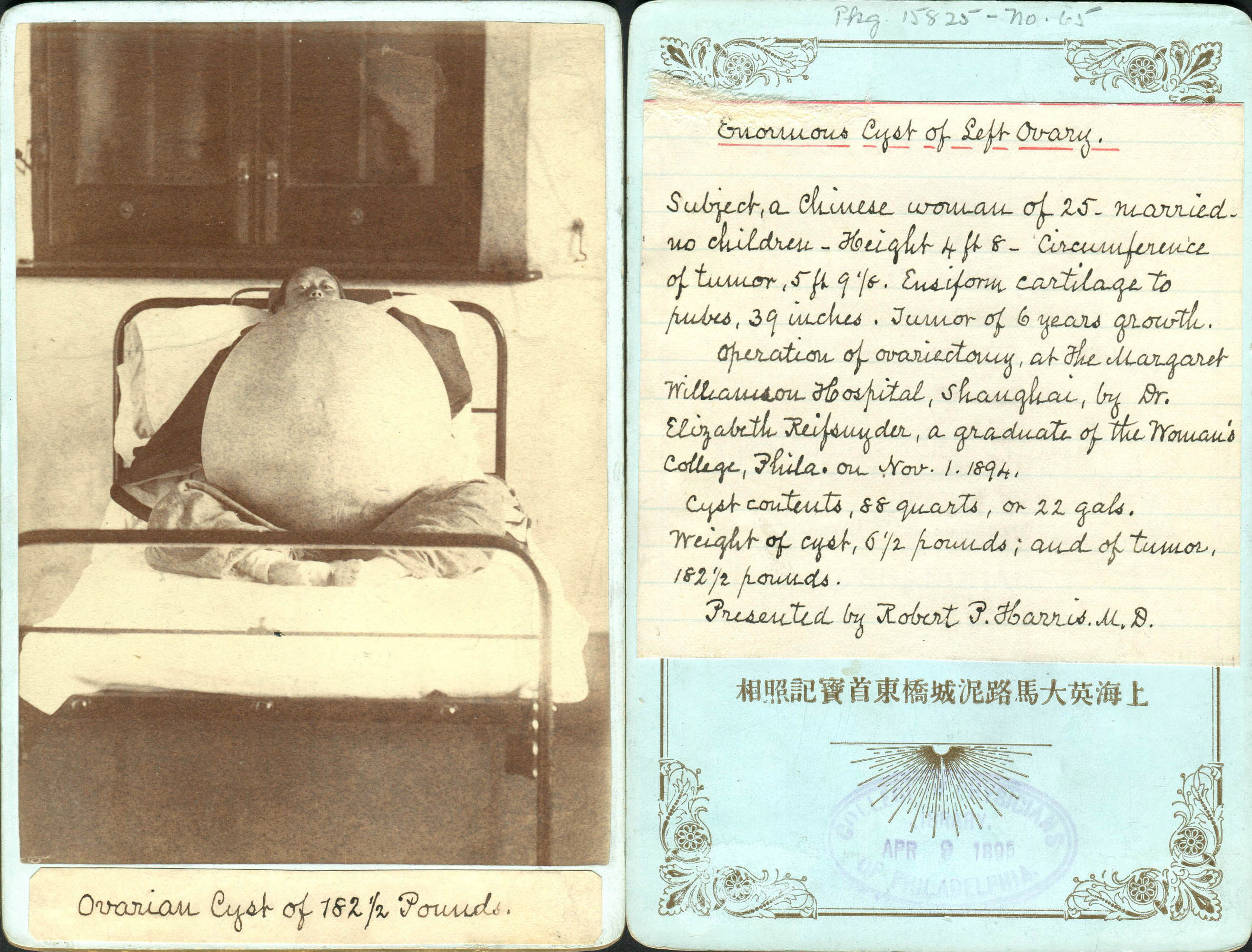

Figure 27 Photographer unknown. “Ovarian Cyst of 182 1/2

Pounds,” 1894. Front and back

views. Courtesy the Historical

Medical Library of the College of

Physicians of Philadelphia.Figure 28

Photographer unknown. “Ovarian Cyst of 182 1/2

Pounds,” 1894. Front and back

views. Courtesy the Historical

Medical Library of the College of

Physicians of Philadelphia.Figure 28 Photographer unknown. “Yu Yung

Lan. 4 ft 8 … 2 months after

operation,” 1895. Front and back

views. Courtesy the Historical

Medical Library of the College of

Physicians of Philadelphia.

Photographer unknown. “Yu Yung

Lan. 4 ft 8 … 2 months after

operation,” 1895. Front and back

views. Courtesy the Historical

Medical Library of the College of

Physicians of Philadelphia.

Returning to the Haseki portrait album, I wondered how we might

make sense of the surgeon’s signature on each plate (and also on each

abdomen in the form of a scar), despite the images having been made by

a prominent studio photographer? How does this album ask us to rethink

agency in photography? The examples from St. Petersburg and Shanghai p. 50 each point to complex webs of power dynamics between patients and

doctors and emerging medical establishments, yet aesthetically they are

much closer to the genre of medical photography of illness or pathological

specimens than to the portraits of Haseki patients taken by Andriomenos.

Still puzzling through why these photographs might have been taken,

I came across a court record of a malpractice case brought against

Nurettin.32 A clerk had charged him with negligence leading to the death

of the clerk’s wife and child during childbirth. The case had been seen a

second time after the clerk appealed the initial ruling, but Nurettin had

eventually been acquitted. Unfortunately, only the acquittal decision,

dated May 8, 1892, remains, so I do not know the date of the tragic incident

or that of the original trial, only that this happened in the two years

prior; that is, in the time that had elapsed since Nurettin’s arrival at the

hospital in 1890. Whether the photographs were produced before, after,

or during the time Nurettin was defending himself against charges of

medical negligence, it is likely that the production of the Haseki portrait

album and the malpractice case overlapped: both correspond to roughly

the same period of the young doctor’s life.

Finally, I found a document in the Ottoman archives dated December

2, 1890, sent from the Ottoman municipal health officer to Sultan

Abdülhamīd confirming that the portrait album was but one way of notifying

the sultan about the successful surgeries Nurettin had performed.

The document tells us about twenty-two-year-old Gülizar Hatun, whose

child had died in the womb:

She was sent to Haseki Hospital last night… . Dr. Ahmed Nurettin

who was on call determined that because her structure was not

suitable there was no natural way to birth the child who had died

two days prior. Upon Dr. Nurettin’s immediately sending word, the

council of doctors met and decided to perform a caesarean. Ahmed

Nurettin was able to perform the surgery in 20 minutes and the

woman in question seemed to be in good health.33

The letter, written the day after the surgery, ends by praising both the surgeon

and the sultan: “Caesareans are important surgeries and are easily

performed by surgeons trained in the medical schools established by his

majesty in hospitals furnished by his majesty. We understand from the

report of the chief doctor of Haseki Hospital that patients offer many

prayers of gratitude to the sultan.”

To put into context Nurettin’s surgical prowess, and the modesty

of the claim that cesareans were easily performed, consider his U.S.

contemporary Howard Kelly. In April 1888, Kelly performed a caesarean

section, the first in Philadelphia in half a century where the mother p. 51 survived. This was hardly seen as an easily performed surgery. Kelly’s

successful completion of three subsequent caesareans was seen as such

an accomplishment that he was named assistant professor of obstetrics

at the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school, and the following year

(at the young age of thirty-one) he was made one of the founding

members—one of the “Big Four”—of the medical faculty of Johns

Hopkins University.34

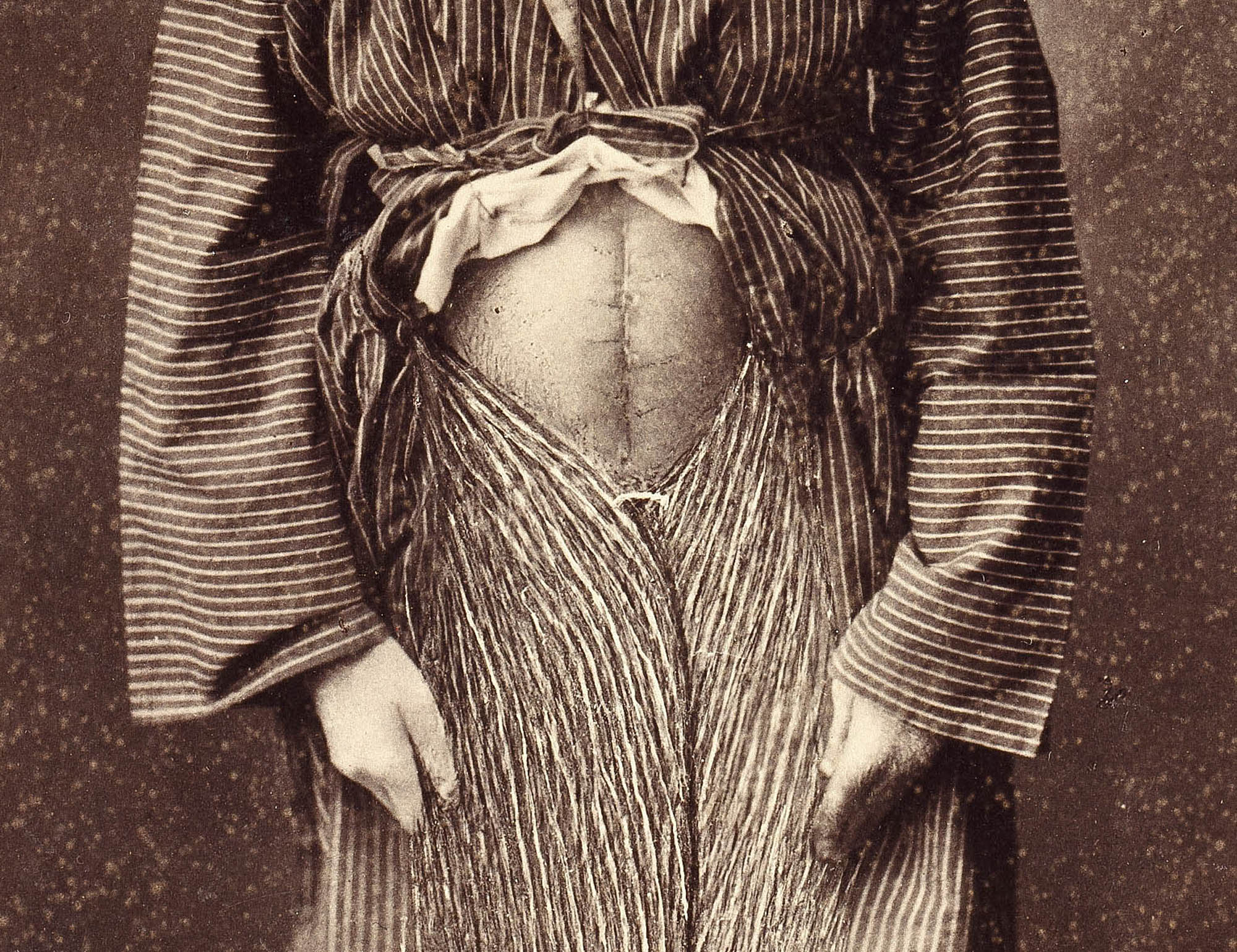

Prompted by these documents, I went back to Gülizar’s photograph.

And I discovered a clue. Despite having spent seven years working on

the Haseki portrait album, I saw something I had never noticed. What I

now saw had been in plain sight all along, but I had not been able to

detect it as a clue. I had always thought of Gülizar’s portrait as the exception

in the album—the woman alone without that which had been

removed made visible. A photograph without a clear backdrop, perhaps

not taken in the photographer’s studio. Moreover, the photograph had

always seemed less sharp to me than the others. In reality, it was my own

lack of focus that was at issue. For when I looked closely, I saw that the

glass plate had been skillfully doctored by the photographer. Gülizar had

initially been photographed revealing much more than her midriff. The

folds of the front of her gown had been fabricated, complete with an

entirely fictional linchpin that seeks to secure not only Gülizar’s gown

but the propriety of the image.35 Propriety would have been essential for

this gift of photographs to arrive at its destination. Ottoman court historians

told me that the album would have easily passed through the hands

of a dozen clerks before reaching the sultan.

Figure 29 Nicolas Andriomenos or

unknown photographer. Gülizar

Kadın, 1891. Image 4, Haseki

Women’s Hospital album formerly

part of Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız

Palace collection. Detail showing

that the original glass-plate negative

had been painted over to

close Gülizar’s gown over her

lower body. She had been photographed

holding her gown

open. The area below her scar

and between her hands has been

overpainted to simulate the cloth

of her gown. İstanbul Üniversitesi

Nadir Eserler Kütüphanesi

(Istanbul University Library of

Rare Books).

Nicolas Andriomenos or

unknown photographer. Gülizar

Kadın, 1891. Image 4, Haseki

Women’s Hospital album formerly

part of Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız

Palace collection. Detail showing

that the original glass-plate negative

had been painted over to

close Gülizar’s gown over her

lower body. She had been photographed

holding her gown

open. The area below her scar

and between her hands has been

overpainted to simulate the cloth

of her gown. İstanbul Üniversitesi

Nadir Eserler Kütüphanesi

(Istanbul University Library of

Rare Books).

Frustrated that I did not know the date of the clerk’s wife dying in

childbirth or the date on which the clerk brought charges of malpractice

against Nurettin, I looked at the photograph for anything that could be

dated. Another visual detail, yet again one that had always been visible,

emerged as a clue. Scars are also time-based media: perhaps a trained eye

could read the time since her surgery in the photograph of Gülizar’s scar.

I consulted with the oldest gynecologists and obstetricians I could find

and asked them to date the women’s surgeries based on how well the

scars had healed. In an attempt to make the process easier, I sent digital p. 51 copies of the images and asked them to zoom in on the surgery scars. They told me the photographs were not taken immediately after the surgeries

but rather at least three months after the incisions had been made.36

Historical records talk about some poor patients at Haseki staying for

lengthy recoveries, often because they had nowhere to go. The document

sent to the palace the morning after Gülizar’s caesarean mentions that

she had been sent over from the shelter for poor women without specifying

whether this was the hospital’s own shelter or another municipal

women’s shelter.37 Gülizar might not have returned to the hospital to

pose for her photograph because she might never have left. Gülizar’s photograph

in the album sent to the sultan indexes several moments of time:

the night of the surgery, the day the photograph was made, the moment

it was carefully doctored, and the decision to include it in the album

with the portraits of women and their tumors.

For a while I was content. The doctor and the photographer had made

a bold choice to photograph this young woman fully exposed upon

recovery from her surgery to reflect the surgeon’s exceptional skill: At a

time when surviving a caesarean was by no means guaranteed, here

stood Gülizar as a picture of health. Gülizar’s is the only portrait whose

caption even in the second nonidentical album includes the descriptor

“picture of health.” Had the doctor and photographer taken the photograph

without any intent to send it and then doctored it later for the eyes

of the sovereign? Or in anticipation of the many others whose eyes the

album would pass before reaching the sovereign? Perhaps this had been

the first portrait made in the series?

Yet something nagged at me at night. Social norms do not change

overnight. Nurettin almost certainly knew of the difficulties encountered

by the former director of Haseki hospital, Kiryako, the young doctor who

was accused of looking inappropriately at his Muslim female patients.

Kiryako’s ordeal had ended with him being reinstated as chief doctor just

five years before Gülizar’s surgery. Would taking a photograph of an

exposed Gülizar not have been considered dangerous? The malpractice

suit brought by the clerk against Nurettin almost certainly predates the

moment the photographer and doctor photographed Gülizar. Would

Nurettin not have been especially cautious to avoid arousing suspicions

during such a trial?

I sought out a newly retired gynecologist, this time in Istanbul. He

remembered visiting Haseki during his own medical training and seeing

the album (presumably the copy once owned by the hospital) on the desk

of the chief doctor. He described admiring Nurettin’s surgical skills even

many decades after the images had been made. This time, however, I did

not zoom in on Gülizar’s scar and ask him to date it. I showed him the p. 53 full image and shared the document sent to the palace the day after

describing the surgery. An amateur medical historian as well as a doctor,

he immediately asked a question I had not considered, thereby pointing

out yet another clue: Why would the doctors risk Gülizar’s life by performing

a caesarean if the child had already died? “The risks of infection

at the time were so great,” he said, “that the first rule to even consider a

caesarean was confirmation that the child was still alive. Why would Dr.

Nurettin ever attempt such an irresponsible surgery? There must have

been a reason.”

There was. The doctor looked again carefully at the portrait of Gülizar—

not just a zoomed-in image of her surgical scar—but her full portrait. “Of

course! Look at her posture and her miniature stature. This girl had

rickets,” he stated confidently. Her pelvis must have been so deformed, he

concluded, that even if they crushed the child in utero—craniotomy was

the standard way that such a stillborn child would be delivered at the

time—the doctors could not have removed the fetus vaginally.38 Nurettin

performed the caesarean despite the fetus being confirmed dead two

days prior—not at the risk of, but as the only way to save, Gülizar’s life.39

Perhaps it was precisely because he was already being investigated for

malpractice, or at the very least because the judicial system allowed

for such malpractice cases at the time, that Nurettin initially asked the

photographer Andriomenos to take the photograph of Gülizar in a manner

that fully exposed her highly deformed pelvic structure to show not

only that she had survived and was a picture of health but also to explain

why he had undertaken this surgery in defiance of the medical protocols

of the day. Then at some later point Nurettin (or perhaps the photographer

Andriomenos, or perhaps both together) decided it was important

that Gülizar’s photograph as a picture of health be included in the album

on tumors addressed to the sultan. After all, her case had already been

mentioned to him in a letter. But before including the photograph, they

took the precaution of re-dressing her.

Even now, when I can see beyond the fabricated hospital uniform

covering Gülizar’s disfigured pelvis and surmise the set of conditions

that led to her portrait being presented to the sultan in precisely this

manner, I can conclude only by sharing some questions. Some I can venture

to answer; others I can only ask in the hopes that answers might be

unearthed when new clues emerge.40 How is care being visualized in this

album and to what political end? Does the appearance of these images in

an album at the sultan’s palace collapse traditional differences between

medical and political images? What might have been the impact of these

images that show the removal of tumors and serve as testimonies to the

efficacy of medical interventions?

p. 53 Perhaps the images in the Haseki album were a preemptive effort to

protect Nurettin against charges of improper treatment of Muslim

women—such as those brought against his Greek Ottoman predecessor,

Kiryako. After all, each photograph grants indigent women some of the

aesthetic dignity afforded to women of means, those able to commission

their portrait in a prominent photography studio.41

Perhaps the photographs were a visual defense case, a lineup of proof

of Nurettin’s prowess as a surgeon that might serve as insurance against

any malpractice claims brought against him. Nurettin was indeed acquitted

in the malpractice case that concluded in 1892. Moreover, when he

petitioned to travel to Paris for three months at his own expense to study

the latest treatments of diphtheria with the physician Émile Roux in late

1894, he was granted permission.42 Neither the malpractice case nor

any suspicions that might have arisen about his decision to perform a

caesarean on Gülizar given the known death of the fetus seems to have

prevented Nurettin from rising quickly in the ranks.

Perhaps the portraits were intended to proudly display for the sovereign

the results of Nurettin’s surgical talents, to boast of the extraordinary

surgeries performed by a young doctor. After all, Nurettin was

merely twenty-four when he performed the caesarean on Gülizar.43 Upon

his return from Paris, he studied general surgery at Gureba Hospital with

a prominent Ottoman surgeon who had trained in France, and eventually

returned to Haseki in 1903, where he was promoted to hospital

director in 1907.44 Moreover, not only did he have a successful career in

surgery; he was held in high esteem within the medical establishment

and beyond and served in several leadership roles in emerging public

health organizations, such as the Müessesât-ı Hayriye-i Sıhhiye İdaresi

(Administration of Medical Charities in Istanbul).45 According to his

granddaughter, Nurettin was also called on to care for women in the

royal family.46

Perhaps the album served as visual evidence of the miracles of modern

science and the lives being saved in the Ottoman Empire’s hospitals. p. 55 A 1907 document strongly endorsing Nurettin for the directorship of

Haseki Hospital includes a table listing all 121 surgeries performed at the

hospital of which only one resulted in a death.47 These near-perfect

results are deemed to be worthy of the glory of the Ottoman Empire and

the sultan himself, and hence the surgeon’s talents are presented at the

service of the empire’s reputation. A second table sent in June that same

year details surgeries performed since the first report and includes four

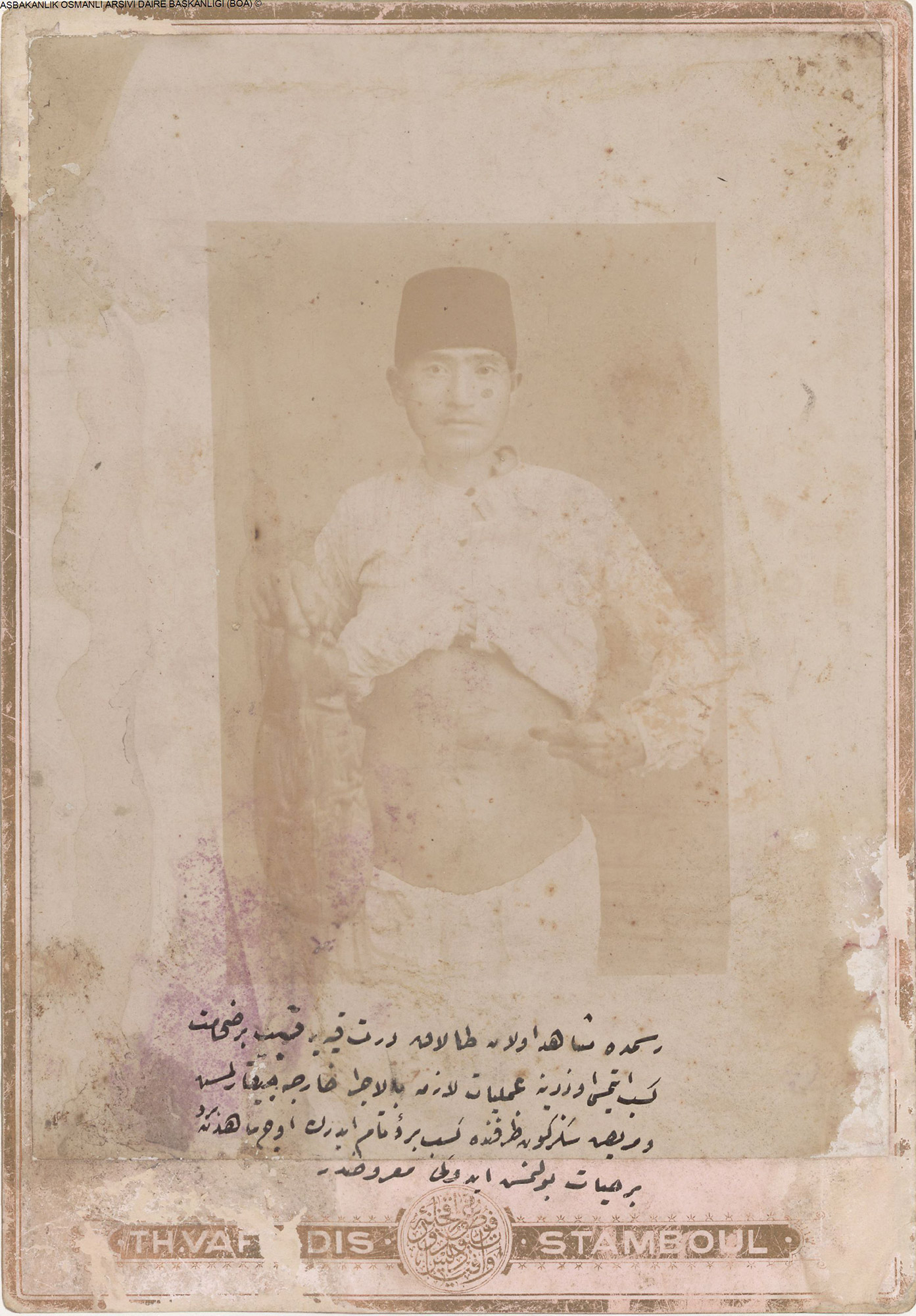

photographs showing patients after their recovery.48 Attention is drawn

to the surgery shown in one of the photographs, deemed to be a particularly

critical surgical intervention. Another album

sent to the palace and titled “Patients who have

undergone surgery” includes nine prints showing

recovering patients and opens with a photograph

taken during surgery itself.49 That print is followed

by one in which the patient being operated

on in the prior photograph, Hüseyin of Arapkir, is

baring his midriff, pointing to his scar with his left

hand while holding in his right hand his removed

spleen, which weighed just over five kilograms.50

The caption emphasizes the extreme rarity and

importance of a patient surviving the surgery and

living without a spleen.51

Figure 30 Unknown photographer. View

of an operation on the patient

Hüseyin at Haseki Women’s

Hospital, Istanbul, ca. 1903–1907.

First image in Ameliyat-I

Cerrahiye İcra Olunan Bazı

Hastalar (Patients who have

undergone surgery), formerly part

of Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız Palace

collection. İstanbul Üniversitesi

Nadir Eserler Kütüphanesi

(Istanbul University Library of

Rare Books).Figure 31

Unknown photographer. View

of an operation on the patient

Hüseyin at Haseki Women’s

Hospital, Istanbul, ca. 1903–1907.

First image in Ameliyat-I

Cerrahiye İcra Olunan Bazı

Hastalar (Patients who have

undergone surgery), formerly part

of Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız Palace

collection. İstanbul Üniversitesi

Nadir Eserler Kütüphanesi

(Istanbul University Library of

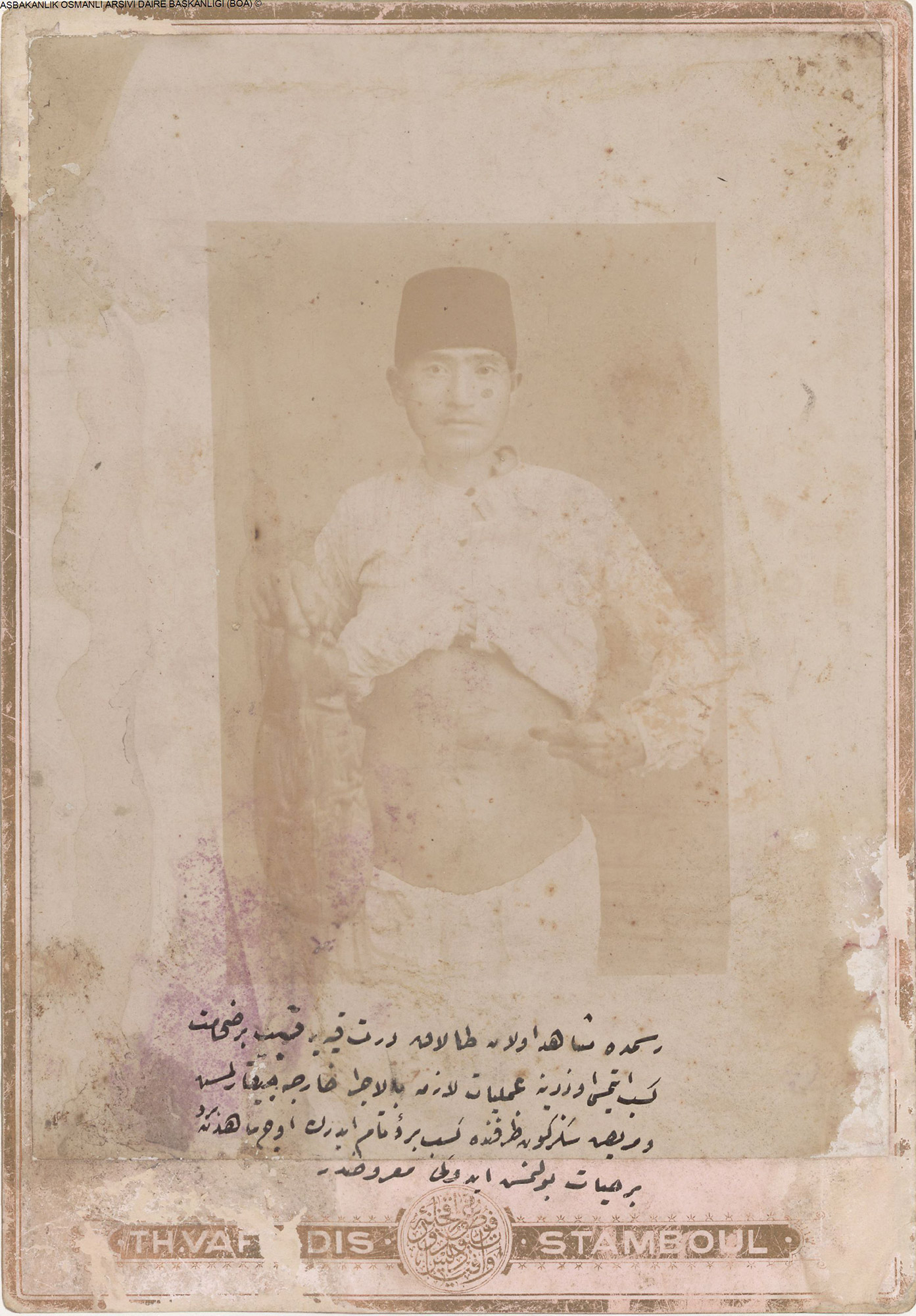

Rare Books).Figure 31 Unknown photographer. Hüseyin

pointing to his scar with his left

hand while holding in his right

hand his removed spleen, ca.

1903–1907. Second image in

Ameliyat-I Cerrahiye İcra Olunan

Bazı Hastalar (Patients who have

undergone surgery), formerly part

of Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız Palace

collection, showing the result of

the operation depicted in the first

image. İstanbul Üniversitesi Nadir

Eserler Kütüphanesi (Istanbul

University Library of Rare Books).Figure 32

Unknown photographer. Hüseyin

pointing to his scar with his left

hand while holding in his right

hand his removed spleen, ca.

1903–1907. Second image in

Ameliyat-I Cerrahiye İcra Olunan

Bazı Hastalar (Patients who have

undergone surgery), formerly part

of Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız Palace

collection, showing the result of

the operation depicted in the first

image. İstanbul Üniversitesi Nadir

Eserler Kütüphanesi (Istanbul

University Library of Rare Books).Figure 32 Unknown photographer. Hüseyin

pointing to his scar with his left

hand while holding in his right

hand his removed spleen, ca.

1903–1907. Second image in

Ameliyat-I Cerrahiye İcra Olunan

Bazı Hastalar (Patients who have

undergone surgery), formerly part

of Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız Palace

collection, showing the result of

the operation depicted in the first

image. This copy of the photograph,

mounted on a pink card

and bearing the imprint of Greek

Ottoman photographer Theodore

Vafiadis, is part of a set of images

of postoperative patients sent to

Ottoman municipal health officials.

Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi

(Prime Ministry Ottoman

Archives).

Unknown photographer. Hüseyin

pointing to his scar with his left

hand while holding in his right

hand his removed spleen, ca.

1903–1907. Second image in

Ameliyat-I Cerrahiye İcra Olunan

Bazı Hastalar (Patients who have

undergone surgery), formerly part

of Abdülhamīd II’s Yıldız Palace

collection, showing the result of

the operation depicted in the first

image. This copy of the photograph,

mounted on a pink card

and bearing the imprint of Greek

Ottoman photographer Theodore

Vafiadis, is part of a set of images

of postoperative patients sent to

Ottoman municipal health officials.

Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi

(Prime Ministry Ottoman

Archives).

These later postoperative and before-and-after

surgery images are useful comparisons to the Haseki

portrait album Nurettin prepared and sent to the

palace in the early 1890s. The later images are

proof that by the first decade of the twentieth century

the genre of surgical photography had consolidated

and become a well-known convention.

Patients are still sometimes identified by name

and place of origin, but these images are no longer

captioned poetically as pictures of health or landscapes

of healing, and they cannot be mistaken for

commissioned studio portraits. While visible

backdrops in some of the photographs suggest

they were taken in prominent Greek photographer

Theodore Vafiadis’s studio, they are stylistically

much more akin to images illustrating accomplishments

in surgery published in journals such

as Revue de photographie médicale or Photography

and Surgery.52 With the exception of the spleen held

by the patient from whom it has been removed, p. 56 tumors or organs removed from the patients are no longer displayed. Gone are the tumors in bell jars on decorative tables. However, the album

of surgery patients sent to the palace includes a print showing a woman

who had survived a caesarean delivery holding a swaddled baby of

several months.

The Turkish gynecologist I consulted with had been deeply impressed

when he was new to the profession and viewed the Haseki portrait

album, suggesting it may have been used as a pedagogical tool. Ottoman

medical students in the nineteenth century learned childbirth by using

charts and illustrations rather than attending actual births. Besim Ömer,

the pioneer of Ottoman obstetrics and gynecology, was not permitted to

establish an official maternity clinic upon his return to Istanbul in 1891

from Paris, where he had been trained. Therefore, he opened an undercover

clinic where young obstetricians learned the basics of their craft by

practicing on the bodies of destitute women.53 One of the allegations

brought against Kiryako that was found to have some validity was that

young doctors and midwives came to Haseki to watch childbirths.

Hence, perhaps the Haseki portrait album was a permissible pedagogical

tool in a climate where offering or receiving medical training could leave

a doctor exposed to charges of impropriety. One indication that the

album may have been seen by other doctors at the time is a photograph

showing a woman who survived a caesarean in 1898, this time photographed

with her baby.54 This cesaerean was performed not by Nurettin

but by Besim Ömer, the young gynecologist making a name for himself at

the time. Similarly, the photograph is signed with his name in 1903. The

resonance between this image and the photograph showing another

woman’s recovery from a caesarean performed at Haseki Hospital suggests

Ömer and Nurettin were aware not only of one another’s surgeries but of

one another’s photographic practices.

Figure 34 Unknown photographer.

Photograph showing a healthy

recovery from a caesarean delivery,

1903. From Fotoğraf albümü: Yıldız

Sarayı, insan fotoğrafları, vazo,

kaide ve çeşitli bina fotoğrafları

(Yıldız Palace, portraits, vases,

pedestals, and architectural photographs).

The caption is penned

by the obstetrician Besim Ömer.

Courtesy Halife Abdülmecid

Efendi Library Collection,

Dolmabahçe Palace, Istanbul.

Unknown photographer.

Photograph showing a healthy

recovery from a caesarean delivery,

1903. From Fotoğraf albümü: Yıldız

Sarayı, insan fotoğrafları, vazo,

kaide ve çeşitli bina fotoğrafları

(Yıldız Palace, portraits, vases,

pedestals, and architectural photographs).

The caption is penned

by the obstetrician Besim Ömer.

Courtesy Halife Abdülmecid

Efendi Library Collection,

Dolmabahçe Palace, Istanbul.

Perhaps the Haseki portrait album was

circulated as a subtle means of showing

gratitude and requesting further funds,

since the sovereign was central to the distribution

of resources? Perhaps the letter

written to the palace the day after Gülizar’s

cesaerean which underscored that caesarean

deliveries could be easily performed

was intended to emphasize that as long

as the sultan continued his financial support

of the empire’s hospitals and medical

school, Ottoman surgeons could effectively

perform the most challenging surgeries. p. 57 The good work of surgeons is seen as a means of augmenting the reputation

of the sultan as kind and benevolent and caring of his subjects. What

the letter reflected back to the sultan was that surviving patients offered

prayers of gratitude not only to their doctors but to the sultan responsible

for the establishment of hospitals and the training of doctors.

Finally, the album was perhaps also intended as a medical argument

for the effectiveness of asepsis. All of the photographed women had survived

a surgery that, due to the high risk of infection at the time, could

be as deadly if not more deadly than the tumors that had led to the need

for operation. The French physician Roux (with whom Nurettin studied

in Paris in 1894) was a major proponent of asepsis, a technique by which

medical facilities—and operating rooms in particular—are kept free of

disease-causing filth. Soon after he arrived as a junior doctor at the hospital

(and thus before he went to Paris), Nurettin, while still the same

rank as when he must have prepared the Haseki portrait album, wrote a

report on the merits of the pavilion system whereby patients are separated

by disease so as to minimize infection.55 This report, endorsed by

the more senior doctors in the hospital, led to the construction of Haseki’s

pavilions.56 Hence, the Haseki portrait album may also have been part of

a persuasive plea for changes in medical curricula and hospital architecture

most conducive to effective surgical hygiene.57 Nurettin eventually

headed a commission for public health policy in Istanbul charged with

effectively preventing and containing the spread of infectious diseases.

Regardless of Andriomenos’s or Nurettin’s initial intentions, the visualization

of care in the Haseki portrait album made many arguments

simultaneously: establishing prestige, protecting and augmenting reputations,

protecting professional standing, fund-raising, advocating for

certain medical procedures and architecture, illustrating modernity, reifying

sovereign power, subjecting to scrutiny but

also dignifying indigent women, and managing

competing proprieties (religious and cultural

norms versus medical norms).

There is no single discovery at the conclusion

of this detective narrative. Rather, I have

tried to show how clues became detectable

over nearly a decade of investigation. Asking

the same question in multiple ways, with multiple

tools and by consulting multiple sources

and experts can help us as scholars see afresh

rather than merely confirm what we believe

we have already seen. The Haseki portrait

album required that I look closely not only at p. 58 each image but take seriously the album as an object and a collection of

images. Many of the clues in this research emerged only when I moved

away from both single images and the broad category of medical photography

and considered how the album might have been constructed or

through what routes it circulated. Genres can be powerful clues if, rather

than serve as fixed identification charts to hold images up to, they provoke

us to ask under what conditions they emerged. The Haseki portrait album

illustrates the unsettlement that characterizes the period before a genre

is consolidated. Photographs rarely conform to strict genre conventions,

and precisely in the places where they do not—where different conventions

clash or where deviations or dissonances can be detected as clues—we

can begin to see new kinds of formations emerging or investigate unresolved

tensions over competing demands for visibility and propriety.

In the process of preparing the images in this article for publication,

I detected, perhaps fittingly, one final clue. Looking upon Gülizar’s portrait

again, this time in conversation with a photographer knowledgeable

about historical processes, we noticed that the glass plate had been

signed before “Dr. A. Noureddin” was carefully written in the corner.

The simple statement “your servant doctor” (tabip kulları) seems to have

been etched into the glass plate before the doctor’s signature. I cannot be

certain of this, for efforts have been made to erase the writing both above

Nurettin’s signature and that to the left of Gülizar. The letters on the left

suggest the name of a photographer, though one that has not appeared in

my searches in the archives. Perhaps Nurettin asked a less-well-known

photographer (maybe even one without his own studio) to take the original

photograph of Gülizar baring her twisted pelvis to serve as evidence

for what had necessitated the unconventional caesarean. Perhaps this was

prompted by a malpractice suit. However, when the decision was made

to doctor the image, perhaps the original photographer did not have the

proper skills and Nurettin approached Andriomenos (one of the prominent

portraitists of the era) not to make a photograph but to remake one

taken by another photographer into an image that could be circulated.

Perhaps that encounter sparked the larger collaboration that resulted in

the Haseki portrait album.