Abstract

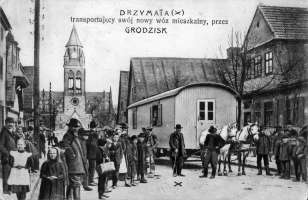

In 1908, in partitioned Poland, a small, spontaneous procession formed along the streets of Grodzisk Mazowiecki as the peasant farmer Michał Drzymała, a humble figure in the Polish independence movement, walked his wagon (wóz), described in the press as “the Polish village on wheels,” toward the town’s central train station. Drzymała was transporting his new carriage back to a small plot of land he owned in the district of Poznań (or Posen, as it was known at the time). A 1904 amendment to the 1886 Settlement Law had forbidden him to build a home on his newly purchased land. The purpose of the amendment, concealed in paragraph 13b, was to enable local officials to deny building permits to Poles solely on the grounds of ethnicity: “In order to ward off such dangers,” the law stated, “the provision of 13b is to be used emphatically and unrestrictedly everywhere.” Hundreds of building applications were thereafter denied each day to Polish applicants across the Prussian-Polish territories. The law, however, went a step further when it claimed that any place where one was stationary for more than twenty-four hours was to be legally considered a home. In 1904, Drzymała, in an attempt to circumvent the new restrictions in Prussian Poland, moved his family into an abandoned circus caravan (later updated with a new carriage, paid for by donations), and for the next five years he moved its position several meters each day. The wagon and its transgressive circulations had become unwitting symbols of the occupied nation and its resistance to the colonial building regime in the region, administered by the Prussian state under the aegis of the Royal Prussian Settlement Commission (RPSC).

The legislative response generated by Drzymała’s act of refusal illustrates a significant if little discussed point about the heritage of the Settlement Law; namely, that over the course of the RPSC’s campaign, which had confined Drzymała and his family to live in a pattern of continual and coerced movement across his own land, several of its legal provisions were applied nationally as federal policy. The Verein für Socialpolitik played a pivotal role in this transfer of practices, further illustrating the entangled relationship that had developed by this time between the state’s interior land-use and housing policies and the urbanization schemes of its various colonial regimes. A careful study of these entanglements, moreover, reveals what Partha Chatterjee calls “a rule of colonial difference”—a mode of representing the “other” as “radically different, and hence incorrigibly inferior,” a constitutive feature, he argues,of modern forms of disciplinary power—operating across the German territories, not only in formal colonial or partitioned domains but in architectural and urban situations that were not, in any strict sense of the term, colonial. It likewise discloses the reciprocal constitution, and shared historical legacies, of certain colonial practices in the German-controlled regions of Eastern Europe and in the African colonial territories, histories typically understood as independent of one another, their continuities made visible in the mechanisms generated by what the historian Helmut Walser Smith calls “the imagination of expulsion” traced here.