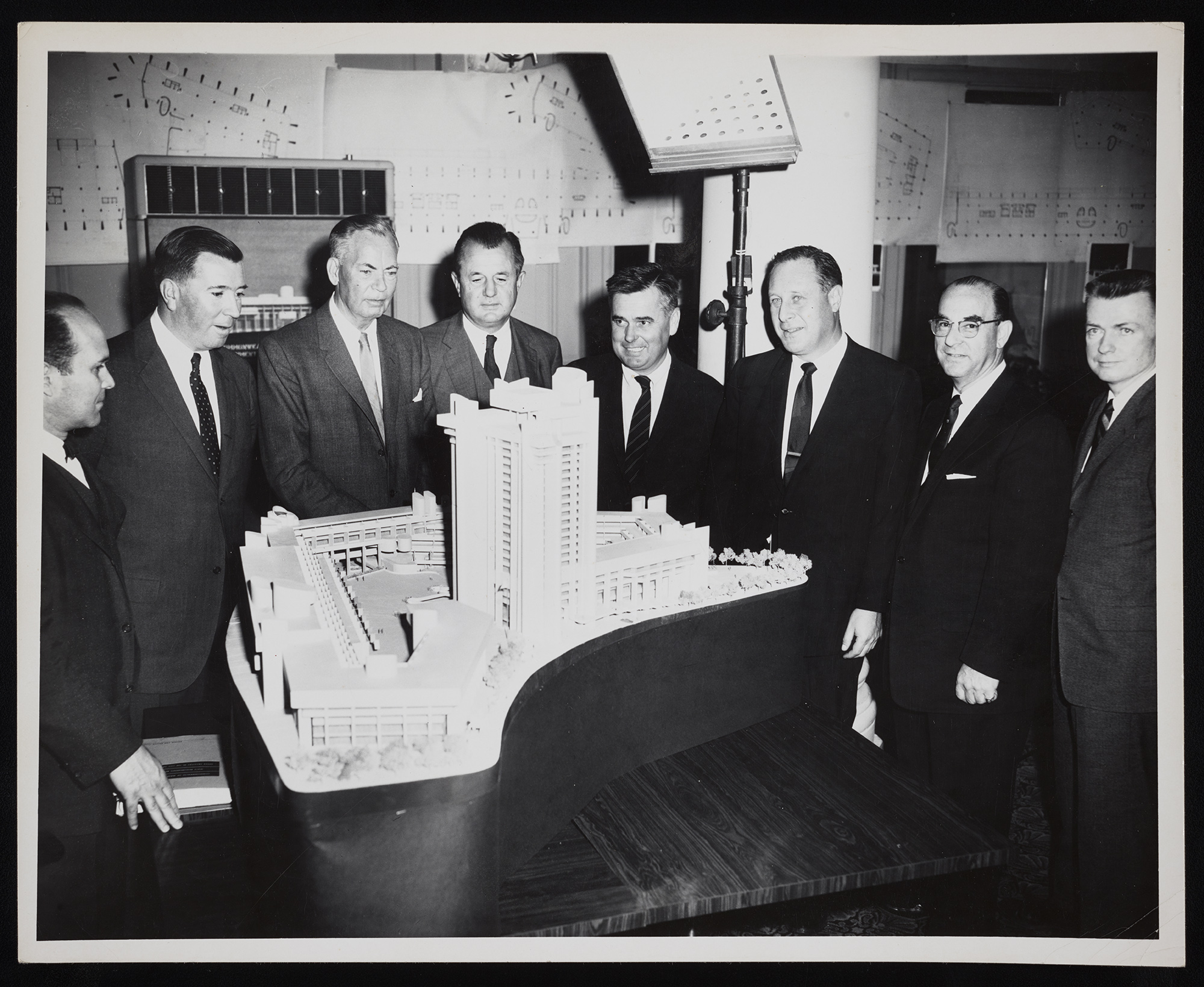

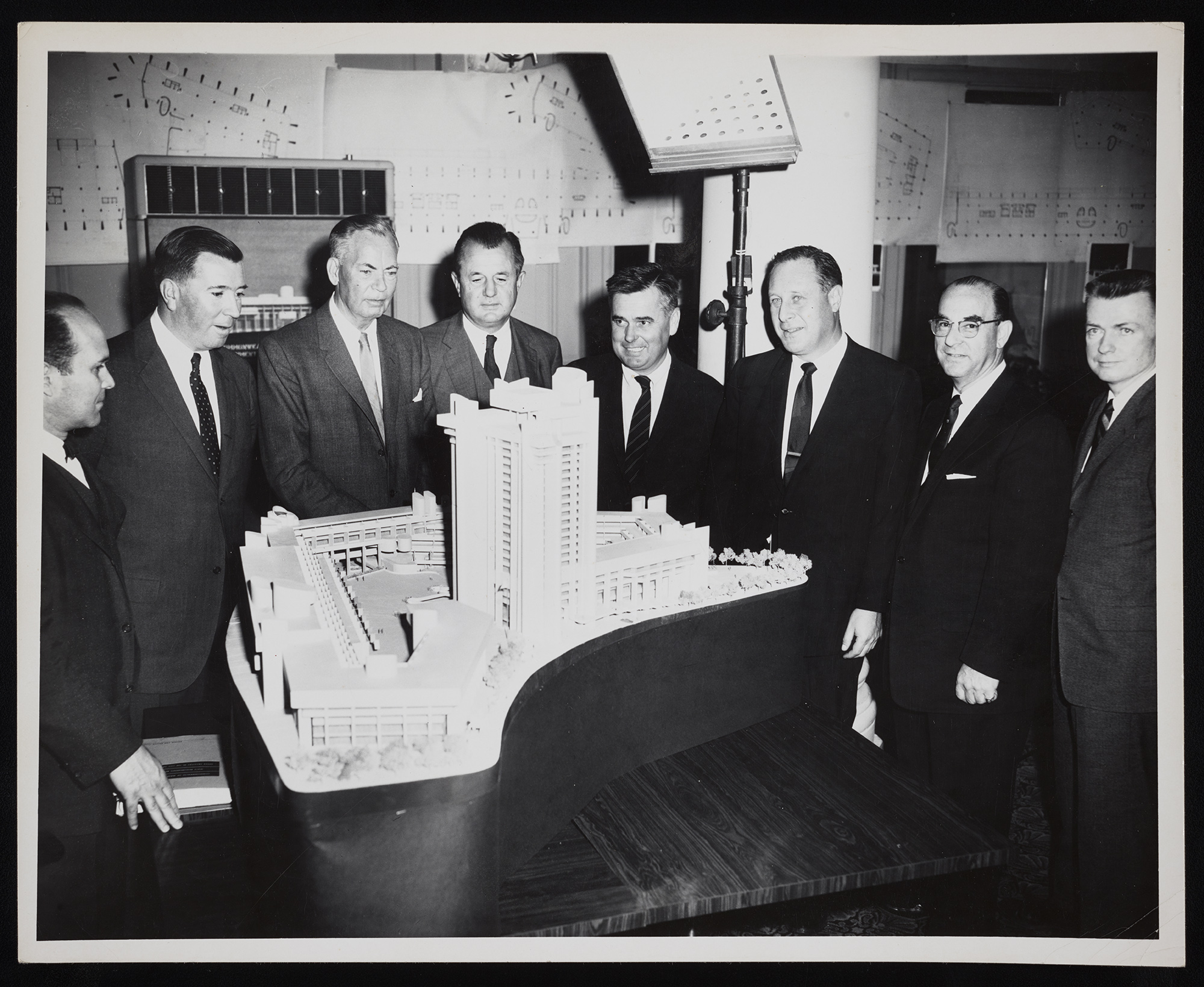

Figure 1 Photographer unknown. Group portrait around Massachusetts State Service Center model, November 1963. Left to right: Nathaniel Becker, Dick Thissen, Charles Gibbons, Joseph P. Richardson, Edward Logue, Jeremiah Sundell, Unidentified (George Berlow or William Pedersen?), Paul Rudolph. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, PMR-3016-3, folder 9.p. 97

Photographer unknown. Group portrait around Massachusetts State Service Center model, November 1963. Left to right: Nathaniel Becker, Dick Thissen, Charles Gibbons, Joseph P. Richardson, Edward Logue, Jeremiah Sundell, Unidentified (George Berlow or William Pedersen?), Paul Rudolph. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, PMR-3016-3, folder 9.p. 97

In 1962, Massachusetts officials devised an unusual plan to unveil an architectural model of a new state office building for Boston’s Government Center urban renewal district during the halftime of a televised professional football game. Whether the grand reveal took place at the Patriots game in Harvard Stadium that September is unknown.1 But the intention speaks to the promise of a moment in American history: connecting the mass media of television and architecture to popular culture and activist government. A year later, in November 1963, a second major state building project was heralded more conventionally at a Boston restaurant near the Massachusetts State House.2 A photograph from that month shows a model of the proposed design of the Massachusetts State Service Center.3 A ring of low, monumental buildings on a triangular site encloses an open plaza, punctuated by a high, sculptural tower. The complex would accommodate headquarters offices and public facilities that Massachusetts citizens would need to visit for employment, mental health, benefits assistance, and additional social services; that is, the complex would host the apparatus of a welfare state.

Figure 2 Shepley Bulfinch Richardson and Abbott. Cambridge Street front, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1962–1972. Photograph: Daniel M. Abramson, 2019 Today, the Massachusetts State Service Center stands in relative neglect. Chips mar the high, vertical piers, dropping concrete shards at one’s feet. Extraordinary exterior stairs once invited entrance. But these are now fenced off, crumbling and inaccessible. In the interior plaza, terraces and concrete sunshades enclose a vast paved void. When work finished in 1972, the planned tower remained unbuilt, substituted by a stylistically divergent postmodern courthouse in the 1990s, when modernism and big government were both in eclipse. To many people still, the Massachusetts State Service Center’s incomplete, decayed condition symbolizes modern architecture’s failures, if not government’s too (notwithstanding today’s midcentury modernism renaissance and Medicare for All campaign). The State Service Center complex hovers in suspension. Will it be rejuvenated, further neglected, or even demolished? Its future may depend on how its past is represented. This article offers a new reading of the Massachusetts State Service Center’s architectural history as an allegory of the American welfare state’s historical tensions, between consolidation and individuation, and its creation of citizens’ subjectivities. This story is convoluted and open-ended, which, like p. 98 allegory, “cannot be read singly.”4

Shepley Bulfinch Richardson and Abbott. Cambridge Street front, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1962–1972. Photograph: Daniel M. Abramson, 2019 Today, the Massachusetts State Service Center stands in relative neglect. Chips mar the high, vertical piers, dropping concrete shards at one’s feet. Extraordinary exterior stairs once invited entrance. But these are now fenced off, crumbling and inaccessible. In the interior plaza, terraces and concrete sunshades enclose a vast paved void. When work finished in 1972, the planned tower remained unbuilt, substituted by a stylistically divergent postmodern courthouse in the 1990s, when modernism and big government were both in eclipse. To many people still, the Massachusetts State Service Center’s incomplete, decayed condition symbolizes modern architecture’s failures, if not government’s too (notwithstanding today’s midcentury modernism renaissance and Medicare for All campaign). The State Service Center complex hovers in suspension. Will it be rejuvenated, further neglected, or even demolished? Its future may depend on how its past is represented. This article offers a new reading of the Massachusetts State Service Center’s architectural history as an allegory of the American welfare state’s historical tensions, between consolidation and individuation, and its creation of citizens’ subjectivities. This story is convoluted and open-ended, which, like p. 98 allegory, “cannot be read singly.”4

Figure 3 Paul Rudolph. Lindemann Mental Health Center, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1962–1972 (at left).Shepley Bulfinch Richardson and Abbott. Charles F. Hurley (Division of Employment Security) Building, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1962–1972 (at right). Photograph: Yukio Futagawa, 1972. © Yukio Futagawa. Today, the Massachusetts State Service Center is best known in architecture circles for being the work of Paul Rudolph.5 For decades the State Service Center has also been popularly excoriated for its off-putting brutalist style and for embodying, in the words of one author, “The Architecture of Madness.”6 These biographical and stylistic perspectives make sense of an otherwise obtuse architecture, through symbolizations of heroic individualism and institutional failure. But they need correcting. While Rudolph was central to the State Service Center’s genesis, he was not its only author. The architect was initially enlisted in 1962 as a design consultant to Desmond & Lord, the local firm designated by Massachusetts officials to build the center’s mental health building. Rudolph’s involvement likely came at the suggestion of Edward Logue, head of the Boston Redevelopment Agency, who had worked with Rudolph when Logue was an urban renewal administrator in New Haven in the late 1950s. Rudolph brought design cachet to the State Service Center project, his career was in the ascendant, and he sought to expand his role at the Boston complex. In 1963, he was named the “coordinating consulting architect” for the whole—“to insure that the design intent is carried out in consistent fashion throughout the project.”7 Rudolph opened a small Boston office, which he visited more or less weekly until work on the center stopped in 1972. Figure 4

Paul Rudolph. Lindemann Mental Health Center, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1962–1972 (at left).Shepley Bulfinch Richardson and Abbott. Charles F. Hurley (Division of Employment Security) Building, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1962–1972 (at right). Photograph: Yukio Futagawa, 1972. © Yukio Futagawa. Today, the Massachusetts State Service Center is best known in architecture circles for being the work of Paul Rudolph.5 For decades the State Service Center has also been popularly excoriated for its off-putting brutalist style and for embodying, in the words of one author, “The Architecture of Madness.”6 These biographical and stylistic perspectives make sense of an otherwise obtuse architecture, through symbolizations of heroic individualism and institutional failure. But they need correcting. While Rudolph was central to the State Service Center’s genesis, he was not its only author. The architect was initially enlisted in 1962 as a design consultant to Desmond & Lord, the local firm designated by Massachusetts officials to build the center’s mental health building. Rudolph’s involvement likely came at the suggestion of Edward Logue, head of the Boston Redevelopment Agency, who had worked with Rudolph when Logue was an urban renewal administrator in New Haven in the late 1950s. Rudolph brought design cachet to the State Service Center project, his career was in the ascendant, and he sought to expand his role at the Boston complex. In 1963, he was named the “coordinating consulting architect” for the whole—“to insure that the design intent is carried out in consistent fashion throughout the project.”7 Rudolph opened a small Boston office, which he visited more or less weekly until work on the center stopped in 1972. Figure 4 Paul Rudolph and others. Central plaza, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1962–1972. Photograph: Daniel M. Abramson, 2019.

Paul Rudolph and others. Central plaza, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1962–1972. Photograph: Daniel M. Abramson, 2019.

Figure 5 Paul Rudolph and others. Massachusetts State Service Center, 1962–1972. Aerial view looking north. Photograph: Yukio Futagawa, 1972. © Yukio Futagawa. But Rudolph was just one of many people who had a hand in the Massachusetts State Service Center, as illustrated by a 1963 group portrait. The renowned architect is barely in the frame. Across the table, hugging the left margin, is Nathaniel Becker, head of the New York City space planning firm Becker and Becker, which not only produced the 1960 facilities study (there on the table at Becker’s hand) that led to the commissioning of the State Service Center but also provided extensive planning schemes for the majority of the built center’s functional spaces. Fourth from the left, in vest and dark tie, is the patrician Joseph P. Richardson, grandson of Boston architect H.H. Richardson and senior partner of Shepley Bulfinch Richardson and Abbott (SBRA), the venerable local firm responsible for the State Service Center’s Charles F. Hurley Building, housing the p. 99 Division of Employment Security (DES). “We did design the [Hurley] building,” Richardson wrote in 1970, “and not Rudolph.”8 Second from left stands Dick Thissen, the businessman head of Desmond & Lord who invited Rudolph’s participation. Immediately left of Rudolph is an unidentified man, likely either George Berlow of M.A. Dyer Company, or William Pedersen of Pedersen and Tilney, the latter firm being recent competition winners for an unrealized Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial in Washington. Both offices were engaged on the State Service Center project. Besides these architectural actors, clients, too, appear in the group portrait. Representing the official employer are Government Center Commission (GCC) chair and political functionary Charles Gibbons (third from left) and commissioner and local businessman Jeremiah Sundell (third from right). The GCC oversaw construction and financing, but with a small staff it took a secondary design role to the larger Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA), which in exchange for helping the state obtain the land for Government Center had secured the right to vet its design. Standing in the group portrait’s center is the head of the BRA, stripe-tied and beaming Ed Logue. His staff and advisors p. 100 would play key roles in the Massachusetts State Service Center’s design. Thus, representing the center as Rudolph’s individual achievement obscures others’ contributions, even as it underwrites an ideology of singular control.

Paul Rudolph and others. Massachusetts State Service Center, 1962–1972. Aerial view looking north. Photograph: Yukio Futagawa, 1972. © Yukio Futagawa. But Rudolph was just one of many people who had a hand in the Massachusetts State Service Center, as illustrated by a 1963 group portrait. The renowned architect is barely in the frame. Across the table, hugging the left margin, is Nathaniel Becker, head of the New York City space planning firm Becker and Becker, which not only produced the 1960 facilities study (there on the table at Becker’s hand) that led to the commissioning of the State Service Center but also provided extensive planning schemes for the majority of the built center’s functional spaces. Fourth from the left, in vest and dark tie, is the patrician Joseph P. Richardson, grandson of Boston architect H.H. Richardson and senior partner of Shepley Bulfinch Richardson and Abbott (SBRA), the venerable local firm responsible for the State Service Center’s Charles F. Hurley Building, housing the p. 99 Division of Employment Security (DES). “We did design the [Hurley] building,” Richardson wrote in 1970, “and not Rudolph.”8 Second from left stands Dick Thissen, the businessman head of Desmond & Lord who invited Rudolph’s participation. Immediately left of Rudolph is an unidentified man, likely either George Berlow of M.A. Dyer Company, or William Pedersen of Pedersen and Tilney, the latter firm being recent competition winners for an unrealized Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial in Washington. Both offices were engaged on the State Service Center project. Besides these architectural actors, clients, too, appear in the group portrait. Representing the official employer are Government Center Commission (GCC) chair and political functionary Charles Gibbons (third from left) and commissioner and local businessman Jeremiah Sundell (third from right). The GCC oversaw construction and financing, but with a small staff it took a secondary design role to the larger Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA), which in exchange for helping the state obtain the land for Government Center had secured the right to vet its design. Standing in the group portrait’s center is the head of the BRA, stripe-tied and beaming Ed Logue. His staff and advisors p. 100 would play key roles in the Massachusetts State Service Center’s design. Thus, representing the center as Rudolph’s individual achievement obscures others’ contributions, even as it underwrites an ideology of singular control.

Likewise, representation of the State Service Center’s style as symbolizing institutional dysfunction needs revision. Its creative form was praised in professional circles from its inception to today—and hailed early on, too, in the popular press as part of Boston’s Government Center renewal, “as a city setting the pace among all cities.”9 Erich Lindemann, whose name graces the Mental Health Center, is reported to have disliked the building and called it a “fortress.”10 But his full remarks at the building’s dedication, in September 1971, offer a more nuanced architectural narration of its institutional identity. Its fortified character, Lindemann told his audience that day, represented the limit-setting aspects of psychiatric care. Yet he also suggested that its more free-form spaces embodied psychiatry’s equally valued qualities of “empathy, sympathy, understanding,” which, Lindemann offered, are represented in “this after all quite friendly, charming, lovely, gracious, light-hearted building.”11 Lindemann may have been being publicly polite. But related popular myths about the mental health center’s rough, contorted forms driving patients crazy are belied by an anthropologist’s study of homeless shelter residents living there in the early 1990s. Robert Desjarlais discerned that it was nonresident visitors and staff who most disliked the building. Its inhabitants often did not mind the textured concrete walls, found its labyrinthine spaces comforting, and relished the design’s oddities.12 In recent years, the Lindemann Center’s site director has proudly toured architectural sightseers around the building.13

These then are correctives to perceiving the State Service Center as Rudolph-centric or popularly abhorred. Indeed, for a fuller understanding of the Massachusetts State Service Center we must go beyond biographical and stylistic perspectives altogether and relate the building more complexly to the history of the American welfare state.14 The framework for this interdisciplinary inquiry will be recent questions and debates about welfare states posed by historians and social scientists.15 First, what factors explain the American welfare system’s distinction from Europe’s arrangements? Second, how does culture matter in welfare state studies? Third, what might the future hold for welfare states? The present article addresses these questions from an architectural perspective, looking at issues of integration, subjectivity, and representation as they play out historically, institutionally, and in design. The article also contributes to understanding welfare states’ visual culture, which has hardly been examined, and to the historiography of welfare states’ architecture p. 101 generally, which has been largely focused on Europe and the practical provision of housing. The present study expands that focus by looking at an American administrative and multiservice structure as a complex cultural product.16

SYSTEM AND INTEGRATION

When we talk about welfare states, the European experience, commencing in the late nineteenth century, is often presented as normative: administered by central government and reaching an apogee during a golden age of prosperity circa 1945–1973. Generous public funding and eligibility standards insured against old age and unemployment; aided those impoverished or with disabilities; provided housing, education, and medical assistance as a citizen’s right, not a commodity; and mitigated against economic insecurity under market capitalism. By contrast, the American social service system, while seeking similar ends, has been more private, localized, and heterogeneous, emerging as it did from colonial-era roots in separate towns’ charitable institutions.17 The American system has exhibited constant tension between integration and decentralization, a continually negotiated mixture of government and private entities, administered primarily at the individual state level due to deep anti-federal-government tendencies in American political economy and culture. The American system has also been less generously funded and publicly supported in a society that valorizes self-reliance and that stigmatizes poverty within a capitalist system that is inherently unequal. The birth of the modern American public welfare system during the Great Depression—with New Deal legislation providing federal unemployment, old-age, and poverty benefits—did little to dislodge these deep-seated tensions. Local private charities continued to operate. Individual states administered many of the federal programs. Expanded government regulation to save capitalism from its own crisis did not challenge the system’s private, individual imperatives and inherent inequalities. Novel semipublic, semi private corporations such as the Tennessee Valley Authority helped mitigate expanding central government authority while being popularly presented as producing a grateful citizenry.18 Also culturally, New Deal–era murals helped legitimate the welfare state, smoothing the tension between integration and individuation by presenting national history as acts of heroic individual achievement.19 Victory in the Second World War led to further development of the postwar American welfare state, into what historian Lizabeth Cohen calls the “consumers’ republic.” Here, the dialectic between individuation and consolidation evolves by framing private material and consumer desires as coincident with the nation’s collective prosperity and democratic ideals.20 The consumers’ republic also enacts what sociologist p. 102 Nikolas Rose calls “the governing of the soul,” in which individuals’ subjectivities are created, managed, and “incorporated into the scope and aspirations of public powers.”21 New subjectivities were specifically created in the postwar U.S. welfare system by policy emphases on training, education, and skills, to provide not just a “relief check,” as President John F. Kennedy told Congress in 1962, but “positive services … to help our less fortunate citizens help themselves.”22 Thus the state shifted onto individual citizens the responsibility for their own fate. Still, in the U.S. the citizenry continued to be sorted into those considered worthy of benefits and services (widows, children, male industrial workers, and whites) and those rendered undeserving by federal guidelines and state-level biases (agricultural and domestic workers, women, and blacks). Even within the persistently decentralized, heterogenous U.S. system, Massachusetts at mid-twentieth century stood out for its localism. Each of the state’s three hundred or so towns possessed its own autonomous welfare administration, a fragmentation unmatched anywhere else in the country.23

In the postwar period, against the U.S. system’s congenital decentralization, federal and state-level reformers, Republicans and Democrats alike, pushed strongly for greater integration and standardization to make more efficient and equalize benefits across the growing apparatus, which, in the Cold War context, was meant to embody capitalist democracy’s superiority over communism.24 By1968, reformers in Massachusetts had gained state-level authority over hundreds of individual town offices, instituting uniform professional requirements, often against the resistance of poor, frequently rural communities that valued local knowledge and control.25 Welfare reform reflected larger social changes in a state rapidly shedding industrial working-class jobs in favor of middle-class, white-collar, and professional job growth.26 Thus, architectural design aside, the Massachusetts State Service Center’s very name expresses the dialectic of the American welfare system within a dispersed federalism: between, on the one hand, decentralized administration (“Massachusetts State”) and, on the other, the postwar drive toward integration (“Center”).

The first call for a consolidated Massachusetts State Service Center appeared in Becker and Becker’s 1960 state-commissioned office-facilities study, which recommended that agencies dispersed across more than twenty rented and state-owned buildings in Boston be relocated to a single site.27 At the proposed State Service Center, a mental health unit, previously headquartered in Back Bay and Beacon Hill, would add research facilities and training for psychiatrists, plus extensive new community treatment programs for out- and in-patients closer to their homes. This would replace “old, p. 103 unsafe, and obsolete” rural asylums, explained the mental health department commissioner, Harry C. Solomon, who helped formulate the unit’s program.28 Next, at the State Service Center, the DES, then located in eight offices widely spread across Boston, would be administered from a single structure, the new Charles F. Hurley Building (named for a Depression-era state governor). Upon opening in 1971, it was expected to serve every week some 14,000 unemployment insurance claimants, who would be required to visit the building to receive benefits and services.29 Last, headquartered at the new State Service Center, in a third structure, would be a host of other social service agencies previously accommodated in Back Bay, downtown, and Beacon Hill buildings, including the departments of public health, education, and public welfare, plus related agencies such as the Board of Higher Education and the Commission for the Blind.30

The consolidated Massachusetts State Service Center would be part of the larger Government Center urban renewal district, replacing the cramped, run-down commercial area of Scollay Square with sixty acres of new federal, municipal, and state buildings, plus commercial development, widened thoroughfares, and open spaces. Public urban-renewal dollars were expected to reverse Boston’s economic decline, continuing the New Deal tactic of supporting tottering capitalism with large public projects, now transposed from rural dams to inner cities. The State Service Center’s specific location would be a ten-plus-acre parcel on the western edge of Government Center, sloping downward at the base of Beacon Hill from the State House, close to the North Station rail terminus and Massachusetts General Hospital, and adjacent to the contemporaneous residential West End urban-renewal project that exemplified the period’s convergence of large-scale urban design and governance. In the early 1960s, one planning document recounts, the future site for the State Service Center was a “generally blighted residential neighborhood” of some 150 low-rise brick structures lining a jumble of irregular, narrow streets, and housing more than five hundred low-income families plus more than one hundred retail, wholesale, and manufacturing businesses.31 Following contemporary planning principles, this typical turn-of-the-twentieth-century, inner-city, mixed-use, working-class enclave would be demolished, starting in 1962, t ohouse the new State Service Center on one great, consolidated, triangular superblock bounded by Merrimac, New Chardon, Staniford, and Cambridge Streets, their widths doubled into modern automobile thoroughfares, in accord with the new superblock scale.

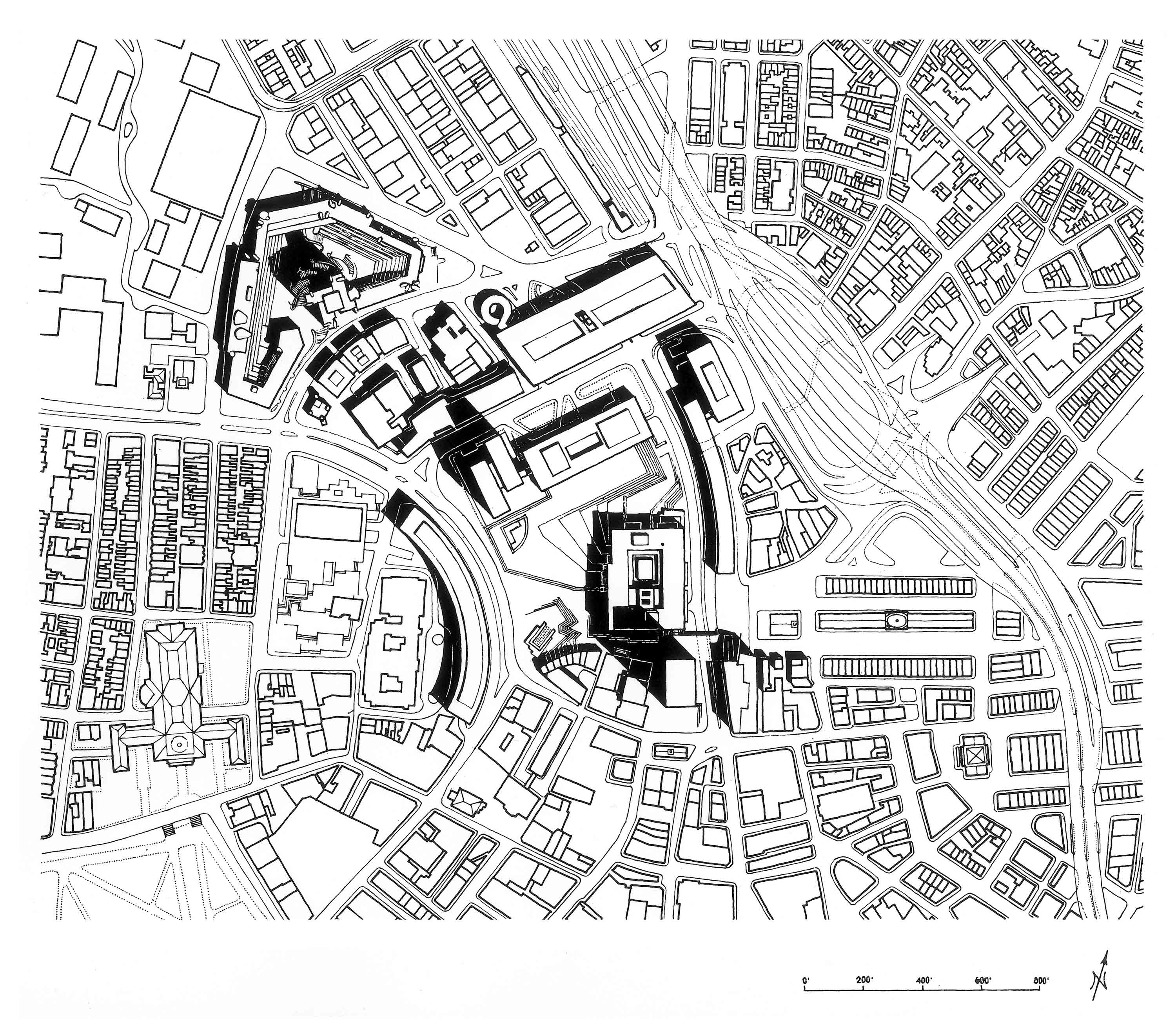

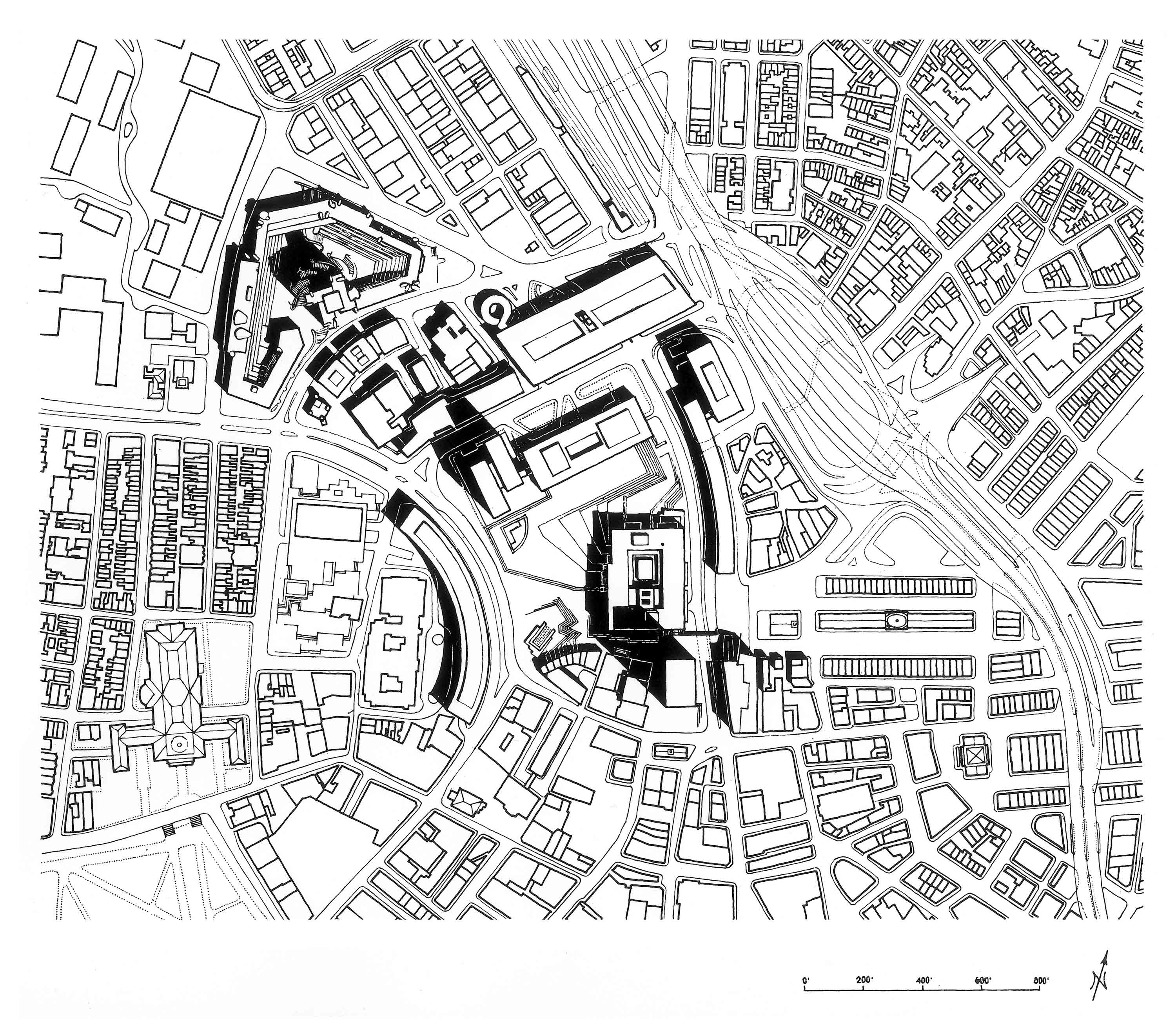

Figure 6 I.M. Pei & Associates. Master plan, Government Center and vicinity, 1964. Courtesy Pei Cobb Freed & Partners. The development of the Massachusetts State Service Center’s architectural design followed an integrative impulse similar to that of the U.S. welfare state and the complex’s own programming and siting. A preliminary 1961 scheme for Government Center’s urban p. 104 design—outsourced by the BRA to the larger staff of architect I.M. Pei’s New York office, with Henry Cobb as lead designer—imagined on the State Service Center site a campus of three separate structures set back from the surrounding streets. A square, high tower paralleled Cambridge Street for the DES. A pair of low, rectangular buildings paralleled Merrimac Street, for Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) and the mental health unit.32 But the Pei-Cobb scheme faced resistance from within the BRA for being an orthodox modernist plan of “three freestanding buildings floating in green space,” in the words of the BRA’s Design Advisory Committee, consisting of prominent Boston-based architects Nelson Aldrich, Pietro Belluschi, and Hugh Stubbins.33 In response, a more integrated design was produced by the BRA-designated consulting architects for the State Service Center complex, local firm Pedersen and Tilney, with Hanford Yang as lead urban designer. The new design featured three zigzag buildings inflected toward one another around a central plaza, with high, concrete towers and low, brick elevations that hugged the street fronts more closely than in the earlier Pei-Cobb design, and opened eastward across New Chardon Street toward the rest of the projected Government Center.34 Still, the BRA design advisory committee, at its April 1962 meeting, told Pedersen and Yang they wanted greater unity. They asked, too, for buildings even nearer to the street edges; for all the buildings’ main entrances to be from the central plaza; and to bring into alignment the irregular massings and heights.35 A month later, BRA director of land planning and design David Crane, previously an urban design instructor at the University of Pennsylvania (where he mentored the young Denise Scott Brown), suggested a wider plaza opening toward New Chardon Street and the rest of Government Center.36 At this stage, with design development in flux, Rudolph intervened. He called a June 1962 meeting of the complex’s architects in his New Haven office. “In a matter of seconds,” he rapidly sketched a site plan that envisioned the State Service Center as a unified ring of low buildings lining the streets, encircling and stepping down into a central plaza, and punctuated by a dramatic, high, pinwheel-plan tower at the complex’s easterly open end toward New Chardon Street.37 Rudolph’s scheme, which p. 105 the other architects agreed to, set the parameters for the State Service Center’s final site plan (other than unifying refinements to smooth the sketch’s street corner angles). Rudolph was proudest of his plan’s high degree of integration, which “read as a single entity rather than three separate buildings.” He further boasted that “in terms of urban design this is undoubtedly one of the first concerted efforts to unify a group of buildings that this country has seen in a number of years.”38 Figure 7

I.M. Pei & Associates. Master plan, Government Center and vicinity, 1964. Courtesy Pei Cobb Freed & Partners. The development of the Massachusetts State Service Center’s architectural design followed an integrative impulse similar to that of the U.S. welfare state and the complex’s own programming and siting. A preliminary 1961 scheme for Government Center’s urban p. 104 design—outsourced by the BRA to the larger staff of architect I.M. Pei’s New York office, with Henry Cobb as lead designer—imagined on the State Service Center site a campus of three separate structures set back from the surrounding streets. A square, high tower paralleled Cambridge Street for the DES. A pair of low, rectangular buildings paralleled Merrimac Street, for Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) and the mental health unit.32 But the Pei-Cobb scheme faced resistance from within the BRA for being an orthodox modernist plan of “three freestanding buildings floating in green space,” in the words of the BRA’s Design Advisory Committee, consisting of prominent Boston-based architects Nelson Aldrich, Pietro Belluschi, and Hugh Stubbins.33 In response, a more integrated design was produced by the BRA-designated consulting architects for the State Service Center complex, local firm Pedersen and Tilney, with Hanford Yang as lead urban designer. The new design featured three zigzag buildings inflected toward one another around a central plaza, with high, concrete towers and low, brick elevations that hugged the street fronts more closely than in the earlier Pei-Cobb design, and opened eastward across New Chardon Street toward the rest of the projected Government Center.34 Still, the BRA design advisory committee, at its April 1962 meeting, told Pedersen and Yang they wanted greater unity. They asked, too, for buildings even nearer to the street edges; for all the buildings’ main entrances to be from the central plaza; and to bring into alignment the irregular massings and heights.35 A month later, BRA director of land planning and design David Crane, previously an urban design instructor at the University of Pennsylvania (where he mentored the young Denise Scott Brown), suggested a wider plaza opening toward New Chardon Street and the rest of Government Center.36 At this stage, with design development in flux, Rudolph intervened. He called a June 1962 meeting of the complex’s architects in his New Haven office. “In a matter of seconds,” he rapidly sketched a site plan that envisioned the State Service Center as a unified ring of low buildings lining the streets, encircling and stepping down into a central plaza, and punctuated by a dramatic, high, pinwheel-plan tower at the complex’s easterly open end toward New Chardon Street.37 Rudolph’s scheme, which p. 105 the other architects agreed to, set the parameters for the State Service Center’s final site plan (other than unifying refinements to smooth the sketch’s street corner angles). Rudolph was proudest of his plan’s high degree of integration, which “read as a single entity rather than three separate buildings.” He further boasted that “in terms of urban design this is undoubtedly one of the first concerted efforts to unify a group of buildings that this country has seen in a number of years.”38 Figure 7 I.M. Pei & Associates. Preliminary site plan, parcel no. 1 and related parcels, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1961. Courtesy the Massachusetts Archives.

I.M. Pei & Associates. Preliminary site plan, parcel no. 1 and related parcels, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1961. Courtesy the Massachusetts Archives.

Figure 8 I.M. Pei & Associates .Master plan, Government Center, April 1962. A preliminary site plan by Pedersen and Tilney for the Massachusetts State Service Center is included at upper left. Courtesy the Boston Planning and Development Agency Archives. Rudolph’s seizure of the moment led to his appointment, at the end of 1962, as coordinating architect for the State Service Center and cemented the legend of his singular authorship of the center’s design. In truth, much of the impetus for the center had preceded Rudolph’s dramatic intervention. Pei’s office had adumbrated the low building/high tower combination. Pedersen and Tilney had produced the first integrated, street-hugging, central plazas cheme opening toward New Chardon Street. The BRA design advisory committee had insisted on greater unification and main plaza entrances for the three buildings. And later in the summer of 1962, after being apprised of Rudolph’s site plan, the BRA urban designer David Crane suggested the street-side elevations’ inverted-terrace massing, which would eventually be realized.39 One of Crane’s other ideas from this time was, however, rejected; namely, that the DES building, along its busy Cambridge Street façade, “be arcaded [and] contain an exterior corridor leading into the plaza.”40 This would have marked a pedestrian entrance into the State Service Center complex from its most public street-front along Cambridge Street, a thoroughfare that links downtown Boston and Government Center and passes through the West End, across the Longfellow Bridge spanning the Charles River, and into Cambridge. But Crane’s reasonable notion, that the State Service Center be visibly accessible at its most trafficked point, was rejected by the DES building’s designer, Jean Paul Carlhian of SBRA, on the grounds, supported by Rudolph and the BRA’s design advisory committee, that “it would be undesirable to duplicate the main entrance to the plaza [from New Chardon Street] with an entrance directly from Cambridge Street.”41 The architects who opposed Crane’s idea apparently believed it was more important to maintain a concentrated unity directed toward p. 106 Government Center than to open and mark the complex for the rest of Boston. At its most prominent point, then, the State Service Center, as built, presents to the city a blank, repetitive façade with neither focus nor entrance.

I.M. Pei & Associates .Master plan, Government Center, April 1962. A preliminary site plan by Pedersen and Tilney for the Massachusetts State Service Center is included at upper left. Courtesy the Boston Planning and Development Agency Archives. Rudolph’s seizure of the moment led to his appointment, at the end of 1962, as coordinating architect for the State Service Center and cemented the legend of his singular authorship of the center’s design. In truth, much of the impetus for the center had preceded Rudolph’s dramatic intervention. Pei’s office had adumbrated the low building/high tower combination. Pedersen and Tilney had produced the first integrated, street-hugging, central plazas cheme opening toward New Chardon Street. The BRA design advisory committee had insisted on greater unification and main plaza entrances for the three buildings. And later in the summer of 1962, after being apprised of Rudolph’s site plan, the BRA urban designer David Crane suggested the street-side elevations’ inverted-terrace massing, which would eventually be realized.39 One of Crane’s other ideas from this time was, however, rejected; namely, that the DES building, along its busy Cambridge Street façade, “be arcaded [and] contain an exterior corridor leading into the plaza.”40 This would have marked a pedestrian entrance into the State Service Center complex from its most public street-front along Cambridge Street, a thoroughfare that links downtown Boston and Government Center and passes through the West End, across the Longfellow Bridge spanning the Charles River, and into Cambridge. But Crane’s reasonable notion, that the State Service Center be visibly accessible at its most trafficked point, was rejected by the DES building’s designer, Jean Paul Carlhian of SBRA, on the grounds, supported by Rudolph and the BRA’s design advisory committee, that “it would be undesirable to duplicate the main entrance to the plaza [from New Chardon Street] with an entrance directly from Cambridge Street.”41 The architects who opposed Crane’s idea apparently believed it was more important to maintain a concentrated unity directed toward p. 106 Government Center than to open and mark the complex for the rest of Boston. At its most prominent point, then, the State Service Center, as built, presents to the city a blank, repetitive façade with neither focus nor entrance.

Figure 9 Paul Rudolph. Sketch of site plan, Massachusetts State Service Center, June 1962. Pinwheel tower is shaded in center. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, PMR-3016-3, folder 10. Rudolph further proposed, and the other architects readily agreed, to further integrate the center’s design by rendering all surfaces, inside and out, in concrete (rejecting Pedersen and Tilney’s earlier brick and concrete division). “If concrete is used consistently throughout,” Rudolph explained to the GCC, “the building will be an honest expression of the validity of concrete as a building material.”42 The monolithic use of concrete, inspired by Le Corbusier’s Marseilles housing project, was in vogue with postwar modern architects because it granted buildings an integrated visual uniformity and structural integrity.43 For the Massachusetts State Service Center, the architects eventually settled on two primary treatments. The vertical columns, towers, and central plaza fins, plus street-front overhangs and many interior surfaces, received rough, textured finishes to emphasize structural capacity and heaviness. Dominant across the center, this “gearworks” finish, as the architects termed it, was produced by pouring concrete into vertical triangular plywood forms. After the concrete had set and the forms had been removed, workers then hammered the revealed pointed, vertical edges to expose the embedded rock and aggregate in a diversity of surfaces, colors, and shapes. Rudolph often used this vertically striated finish, elsewhere called corrugated or corduroy concrete, justifying it to the GCC on aesthetic grounds: “the leading edges are washed by rainfall and are clean, causing the building to catch the light and sparkle.”44 The other primary concrete finish at the State Service Center is smooth “board form,” which appears less massive and is generally used for horizontal elements such as the spandrels beneath the ranges of street-front windows and the ranks of sunshades dominating the central plaza. Overall, the appearance of the concrete building is one of a single unified whole, a further element allegorizing in architecture the integrative impulse of the U.S. welfare state at this time.

Paul Rudolph. Sketch of site plan, Massachusetts State Service Center, June 1962. Pinwheel tower is shaded in center. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, PMR-3016-3, folder 10. Rudolph further proposed, and the other architects readily agreed, to further integrate the center’s design by rendering all surfaces, inside and out, in concrete (rejecting Pedersen and Tilney’s earlier brick and concrete division). “If concrete is used consistently throughout,” Rudolph explained to the GCC, “the building will be an honest expression of the validity of concrete as a building material.”42 The monolithic use of concrete, inspired by Le Corbusier’s Marseilles housing project, was in vogue with postwar modern architects because it granted buildings an integrated visual uniformity and structural integrity.43 For the Massachusetts State Service Center, the architects eventually settled on two primary treatments. The vertical columns, towers, and central plaza fins, plus street-front overhangs and many interior surfaces, received rough, textured finishes to emphasize structural capacity and heaviness. Dominant across the center, this “gearworks” finish, as the architects termed it, was produced by pouring concrete into vertical triangular plywood forms. After the concrete had set and the forms had been removed, workers then hammered the revealed pointed, vertical edges to expose the embedded rock and aggregate in a diversity of surfaces, colors, and shapes. Rudolph often used this vertically striated finish, elsewhere called corrugated or corduroy concrete, justifying it to the GCC on aesthetic grounds: “the leading edges are washed by rainfall and are clean, causing the building to catch the light and sparkle.”44 The other primary concrete finish at the State Service Center is smooth “board form,” which appears less massive and is generally used for horizontal elements such as the spandrels beneath the ranges of street-front windows and the ranks of sunshades dominating the central plaza. Overall, the appearance of the concrete building is one of a single unified whole, a further element allegorizing in architecture the integrative impulse of the U.S. welfare state at this time.

To further unify the complex, and again at Rudolph’s suggestion and with the other architects’ assent, the separate agency buildings were linked under a massive uniform cornice to “heighten,” Rudolph wrote, “the monumentality of the whole.”45 This monumentality would relate to the automobile scale of the widened p. 107 streets, Rudolph explained, and to the renewal site’s superblock size.46 The monumental image would have seemed an appropriate expression, too, for government offices, granting to the complex a Greek-temple-like appearance and authority, with the heavy cornice carried by evenly spaced columns, each articulated as thin, deep “teardrop”-shape piers. On the central plaza elevations, integration of the separate parts was achieved by deploying long runs of horizontal sun shades and projecting vertical fins, creating visual consistency and also a smaller scale than on the street fronts, thus dimensioned to the plaza’s function as an intimate, pedestrian point of gathering and entrance. Figure 10 Paul Rudolph and others. Massachusetts State Service Center, 1962–1972. Details of concrete. Left: “gearworks” finish. Right: “board form.”

Paul Rudolph and others. Massachusetts State Service Center, 1962–1972. Details of concrete. Left: “gearworks” finish. Right: “board form.”

Yet, this overall integrative logic in the State Service Center’s architecture does not overcome inherent tensions. Looked at closely, especially in ground plan, what at first appears to be a single, consolidated structure is revealed as three distinct agency buildings, each of which is divided further into wings split by passages, lobbies, and staircases, that together invite visitors’ exploration and penetration from the sidewalks to the central plaza. What appears massive is thus also porous, a duality evident, too, in the exterior “teardrop”-column colonnades, which appear permeable head-on but as a solid wall when viewed obliquely. Moreover, uniformity of massing and surface did not efface different designers’ distinctive approaches. Rudolph’s Mental Health Center building is accented with dramatic, sculptural towers, hanging stairs, and other curves. But the adjacent DES building elevation along Staniford Street, by the Beaux-Arts trained Carlhian of the more economically minded SBRA office, is restrained, without projecting curves, its cylindrical towers retracted behind the rectilinear cornice, and its Cambridge Street front even more reticent, a mere “foreground” structure, Carlhian explained, to the skyscraper planned to loom behind.47 Additionally, as a contradiction within the integrated design, the placelessness of the modernist scale, abstract forms, and monolithic concrete is belied by contrary localizing impulses and effects, arguably specific to Boston. Rudolph claimed that the setback plazas of the complex’s street corners represented “a reoccurring feature of the city of Boston” and that the “bowl of the [interior] plaza is the counterpart of Beacon Hill and its state house.”48 p. 108 Additionally, the porous, picturesque paths that thread through the complex, inviting citizens’ interaction, reproduce in abstracted form the character of the dense, inner-city neighborhood effaced from the site, a pedestrian experience of the city that urban designers at the time (e.g., MIT’s Kevin Lynch) were starting to revalue.49 Figure 11 Paul Rudolph. Plaza-level plan, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1963. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, PMR-0499.

Paul Rudolph. Plaza-level plan, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1963. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, PMR-0499.

Thus, the State Service Center’s architectural integration is not without contradiction and tension. It is massive and porous, unified and disaggregated, generic and local. And its integrative impulses produce countereffects too. The monolithic concrete endows the building, inside and out, with a hard, even off-putting, feeling. The monumental cornice looms menacingly above passersby. The ranked, rationalistic files of central plaza bays convey a sense of bureaucratic authority. And, the consolidated planning of the three buildings, with their main entrances around the interior plaza, turns the complex in on itself, with the only opening being on-axis toward Government Center’s City Hall Plaza, not the rest of Boston. This hermetic impulse was underscored by the architects’ decision to forego an additional, Cambridge Street entrance. Thus, the architecture of the Massachusetts State Service Center represents, in the complex manner of an allegory, both the U.S. welfare system’s integration at this historical moment and the unintended consequences of an inward-turning, monumental self-regard.

SERVICES AND SUBJECTIVITY

Simultaneous to the U.S. welfare state’s impulse toward integration was a second priority to activate citizens’ subjectivity. Starting in the 1950s, fighting poverty was no longer seen as just a matter of providing cash benefits, as in New Deal–era Social Security and unemployment insurance programs. Rather, reformers sought to develop individuals’ skills and responsibilities. Congressional legislation in 1956 and 1962 tied federal public assistance and unemployment aid to individual states’ provision of job, home-management, educational, day care, counseling, training, and other services. “To assist poor persons and families to retain their sense of dignity and worth,” as a 1965 Massachusetts social services study notes.50 Provision of services meant shifting responsibility to individual agency within the workings of the American welfare system. It modified citizens’ relation to the state from that of passive beneficiaries to that of active p. 109 clients, in the mold of the modern market consumer. The emphasis on services was, in Massachusetts, well-illustrated by reformers’ attempts in the mid-1960s to rename the state’s Department of Public Welfare as the “Department of Social Services.”51 Thus the very title of the Massachusetts State Service Center speaks to a moment in the U.S. welfare system when services grew in significance, in order to produce individuated citizens’ subjectivities.

Figure 12 Paul Rudolph. Chapel, Lindemann Mental Health Center, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1962–1972. Photograph: Edua Wilde, 2014. © Edua Wilde Photography. The Massachusetts State Service Center’s architecture also sought to promote individuated subjectivity. The vast majority of the interior layout of office, clinical, and other working spaces was produced by the space planning firm of Becker and Becker, through a process of abstract calculations of functional units, a rationalism expressed architecturally in the gridded, open, flexible floor plans and the repetition of standardized elements on the exterior elevations. In this situation, Rudolph and his fellow architects were left as designers to focus on subsidiary elements; namely, the curvy parts of the building. These include the vertical, exterior pylons housing stairs, toilets, and other services; the monumental staircases and plazas carved through the structure; arced benches lining the sidewalks; and several dramatic interior areas. Most notably, Rudolph designed the Lindemann Mental Health Center’s in-patient chapel, a traditional psychiatric hospital feature, as an extraordinary double-height, top-lit, all-curved volume. Rudolph intended even more curvilinearity. For the DES building, “another big Baroque curve out at Cambridge Street” was scrapped by SBRA “because of cost,” according to one of that firm’s staff architects.52 In the central plaza, an array of six, waving flights of steps was planned to reach down to the mezzanine level of the unbuilt HEW tower. And inside the low, unbuilt HEW building, Rudolph envisioned an amoeba-shape, 450-seat public auditorium, which would have bulged externally through the gridded façade, above an arc of stairs sweeping up from the radial corner plaza. These curved parts represented for Rudolph strong, individuated forms set against the design’s overall, systematic grid, “clearly p. 110 defined within the regular spacing of the columns,” he explained.53 Figure 13

Paul Rudolph. Chapel, Lindemann Mental Health Center, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1962–1972. Photograph: Edua Wilde, 2014. © Edua Wilde Photography. The Massachusetts State Service Center’s architecture also sought to promote individuated subjectivity. The vast majority of the interior layout of office, clinical, and other working spaces was produced by the space planning firm of Becker and Becker, through a process of abstract calculations of functional units, a rationalism expressed architecturally in the gridded, open, flexible floor plans and the repetition of standardized elements on the exterior elevations. In this situation, Rudolph and his fellow architects were left as designers to focus on subsidiary elements; namely, the curvy parts of the building. These include the vertical, exterior pylons housing stairs, toilets, and other services; the monumental staircases and plazas carved through the structure; arced benches lining the sidewalks; and several dramatic interior areas. Most notably, Rudolph designed the Lindemann Mental Health Center’s in-patient chapel, a traditional psychiatric hospital feature, as an extraordinary double-height, top-lit, all-curved volume. Rudolph intended even more curvilinearity. For the DES building, “another big Baroque curve out at Cambridge Street” was scrapped by SBRA “because of cost,” according to one of that firm’s staff architects.52 In the central plaza, an array of six, waving flights of steps was planned to reach down to the mezzanine level of the unbuilt HEW tower. And inside the low, unbuilt HEW building, Rudolph envisioned an amoeba-shape, 450-seat public auditorium, which would have bulged externally through the gridded façade, above an arc of stairs sweeping up from the radial corner plaza. These curved parts represented for Rudolph strong, individuated forms set against the design’s overall, systematic grid, “clearly p. 110 defined within the regular spacing of the columns,” he explained.53 Figure 13 Paul Rudolph. East elevation, Health, Education, and Welfare Building, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1964. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, PMR-0484.

Paul Rudolph. East elevation, Health, Education, and Welfare Building, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1964. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, PMR-0484.

At one level, the curved elements of the State Service Center actualized Rudolph’s subjectivity. He drew them obsessively, in variations of the waved steps from New Chardon Street into the central plaza and in a sketch of the chapel’s curves as flows of energy permeating the environment.54 Rudolph’s subjectivity was expressed, too, in his signature handling of concrete as a rough, hand-worked material, which Rudolph authority Timothy Rohan identifies as embodying the architect’s individualism (as opposed to anonymous functionalism).55 The textured concrete and curved parts are essentially ornamental add-ons that supplement the dominant, gridded, functional spaces and structure of the Massachusetts State Service Center. Ornament and curvilinearity represent an architect’s individual, creative subjectivity, as architectural historians observe about such forms in postwar architecture generally.56

At another level, the curved concrete forms of the State Service Center are meant to activate not just an architect’s but beholders’ subjectivities. “We need sequences of space, which arouse one’s curiosity,” Rudolph wrote in 1954.57 The sideways movements, the push and pull up stairs and through constricted spaces create bodily, psychological awareness in the experience of moving through the State Service Center. Emotion and sensory affect would be aroused, too, Rudolph explained, by the “multiple curved surfaces of the walls [that] will catch the light in many different ways and render the total complex as one which will present a constantly changing aspect as the sun moves across the sky.”58 About the specific design for the Lindemann Mental Health Center, Rudolph explained, “an effort has been made to provide a variety of visual experience that will relieve the monotony of daily institutional life.”59 All these effects, intended to promote designers’ and beholders’ subjectivity, can be read as activating and allegorizing through architecture the p. 111 American welfare state’s policy to promote individual agency and responsibility. But this individuated subjectification does not fundamentally alter the overall systemic structures, be they the State Service Center’s dominant impersonal production and design, the welfare state’s bureaucracy, or capitalism’s inherent income inequality and cyclical unemployment.

RECEPTION AND REPRESENTATION

Even as the American welfare state tried to produce subjects with greater individual agency, the system ran up against resentment and resistance, leading to difficulties in reception and representation. In Massachusetts, antagonism grew toward the typically American overlapping layers of federal, state, local, public, and private agencies, which, as commentators noted, “so disorients clients, frustrates workers, and confounds the public,” wrote an analyst in 1967.60 “Public welfare in Massachusetts today is so interdependent that neither client nor observer can make sense of it.”61 Though benefits and services increased in the mid-1960s—thanks to expansions in Medicaid, food stamps, and eligibility during the War on Poverty—clients still saw themselves as underserved and alienated, disrespected within an impersonal administration. In Boston, in June 1967, black welfare recipients felt so aggrieved that a local group, Mothers for Adequate Welfare, barricaded themselves in the Grove Hall area office for two days and were then forcibly evicted by police, which led to extended rioting in the African-American Roxbury neighborhood.62 In American society at large, antagonism grew too. Many white working- and middle-class Americans came to perceive the welfare system as serving ungrateful, undeserving others, not themselves (this notwithstanding the reality of a nearly universal Social Security retirement benefit). Instead of offering a unifying, communal identity, in the 1960s the American social-service system ended up dividing people by race and class. “In most large cities [welfare] is one of the major—if not the major—cause of public misunderstanding and intergroup hostility and tension,” notes a 1970 study on Massachusetts welfare reform.63 At the representational level, the American welfare state also lacked “effective collective symbols to legitimate the social policies with which it is identified,” sociologist Theda Skocpal notes.64 Thus, the American social service system in the 1960s suffered from a crisis of alienated representation: incomprehensible to its clientele, resented by many other Americans, and lacking successful symbolization.

With the Massachusetts State Service Center’s architecture, representation has also been vexed in the tensions between integration and decentralization, system and subject. Its reception has been troubled as well. To what extent, for example, do beholders of p. 112 Rudolph’s curved, textured concrete forms actually experience the enhanced subjectivity the architect believed those forms could promote? Not much, to judge by the complex’s subsequent reception. While architects and professional critics have lauded the State Service Center as “progressive,” “brilliant,” and “masterful,” popular opinion has consistently derided its off-putting scale and abrasive surfaces.65 “A concrete orgy,” state officials declared the complex in 1970, “catering to architecture vanities.”66 Particular venom was reserved for the mental health unit, whose rough, expressive concrete forms have been deemed “hostile, disorienting, frightening” to patients and staff alike, with articles about it titled “Mad House,” “The Architecture of Madness,” and “Architecture of Insanity.”67 As the setting for the state police headquarters in Martin Scorsese’s 2006 movie The Departed, the complex embodies bureaucratic power, corruption, and secrecy, its architectural image and meaning—a metaphor for the state’s dysfunction—disseminated as a cultural product.

Faced at best with an incomprehensible architecture, inhabitants have looked for more benign meaning, as I learned when working at the DES Hurley Building as a summer word-processing temp in the late-1980s. Upon hearing I studied architectural history, staff told me that the distinctive hook shape of the building literally pictured the state of Massachusetts, with its similarly jutting form of Cape Cod. A modernist architect would hardly intend such kitsch symbolism.68 The forms Rudolph wanted observers to apprehend phenomenologically, inhabitants have instead insisted on reading figuratively. The complex’s angles and curves have been interpreted as marine imagery (even frogs’ faces), allegedly symbolizing Boston’s coastal location.69 In one instance, the architects did try to inject overt heraldry into the complex. Rudolph proposed hanging American state flags in the central plaza “to add color and movement to an otherwise monochromatic composition.”70 But this would have wrongly identified the Massachusetts State Service Center as a federal rather than state institution (it would have been more appropriate to fly Massachusetts town flags). Indeed, the architects were never seriously interested in denoting the complex’s specific functions and significance within the American welfare system. For them, truth in architecture lay in the experience of abstract form and space, not in legible symbols much less a complicated allegory, as I have developed here, related to the institution’s identity within the U.S. social service system. So antagonism, misrepresentation, and incomprehension have characterized the Massachusetts State Service Center’s architecture just as much as these problems have vexed the American welfare state. p. 113

REPRESENTING THE AMERICAN WELFARE SYSTEM

In one place only is the Massachusetts State Service Center’s identity within the American welfare system explicitly rendered. In the DES building lobby, which links Staniford Street and the central inner plaza, the artist Costantino Nivola produced in August 1969 a pair of large wall murals at the invitation of architect Joseph Richardson, whose firm, SBRA, designed this part of the complex and had previously, in the late 1950s, commissioned a mural from Nivola for a Harvard University dining room in Quincy House. Nivola had immigrated to the United States from Sardinia, Italy, in 1939. Through a friendship with Le Corbusier, he became a sought-after artist for architects seeking collaborators, especially in concrete, including Eero Saarinen for his early 1960s Yale University dormitories.71

In designing the DES lobby murals, Nivola’s first priority was “to relate my work aesthetically to its architectural context.”72 Thus, he filled the space from floor to ceiling with what he called a “graffito-fresco”—rendered by carving with a nail down to a lamp-black undercoating beneath white stucco, also painted upon while wet.73 The resulting grainy surface complemented the lobby’s hand-hammered concrete walls, producing in harmony a craft aesthetic that could be said to humanize the agency’s impersonal bureaucracy housed within. For the murals’ visual language, Nivola heeded a concern “about realism vs. abstract design” expressed by DES director Herman LaMark, who wanted Nivola’s work to communicate conventionally.74 Each wall is thus divided into three horizontal strata, ascending from realistic vignettes, to stylized figures and emblems, to large abstract forms. The lowest, realistic stratum, set off for emphasis by blue and red stripes, is “perhaps the most important of the three,” Nivola explains in a printed description accompanying the murals.75

Figure 14 Costantino Nivola. “Unemployment Insurance” mural in Hurley Building lobby, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1969. Nivola based the murals’ content on a DES memorandum that details the agency’s dual functions of “Unemployment Insurance” and “Employment Service.”76 As Nivola explained, the mural on the lobby’s southern wall, centered on the official coat of arms of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, tells in its lower level the story of unemployment insurance turning “distress” into “well-being.”77 From left to right, the first lower-level vignette, representing unemployment and poverty, shows a dilapidated kitchen apartment: bare, broken refrigerator; despairing father with clenched hands; and a sprawl of fighting children beneath the table. Next follows a riotous street scene of trash, mob, and protest (similar to Nivola’s drawings of unrest at the 1968 Chicago Democratic Party convention). Then, as the mural proceeds, the crucial intervention of unemployment insurance cash benefits (represented by a central coin-dispensing hand) leads to a scene of an abundant supermarket cornucopia and, p. 114 in the last vignette, the same kitchen apartment as before but now as the setting for a harmonious family feast: well-coiffed mother, mannered children, and father presiding, hands employed in carving the festive bird. This progression from domestic and urban disorder to order enables the middle symbolic strata in the mural above, which depicts, in highly stylized form, seated father and mother figures cradling their child with “joyousness.” In the topmost frieze, cubic shapes, Nivola explained, could be read as an urban skyline or as “silhouettes of individuals of social importance,” either way symbolizing, atop the whole, “the massive image of modern, authoritative, responsible society.”78 Thus, the layered grid of the mural narrates the self-production and management of the subjectivity, behavior, and identities of family individuals in the service of society.

Costantino Nivola. “Unemployment Insurance” mural in Hurley Building lobby, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1969. Nivola based the murals’ content on a DES memorandum that details the agency’s dual functions of “Unemployment Insurance” and “Employment Service.”76 As Nivola explained, the mural on the lobby’s southern wall, centered on the official coat of arms of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, tells in its lower level the story of unemployment insurance turning “distress” into “well-being.”77 From left to right, the first lower-level vignette, representing unemployment and poverty, shows a dilapidated kitchen apartment: bare, broken refrigerator; despairing father with clenched hands; and a sprawl of fighting children beneath the table. Next follows a riotous street scene of trash, mob, and protest (similar to Nivola’s drawings of unrest at the 1968 Chicago Democratic Party convention). Then, as the mural proceeds, the crucial intervention of unemployment insurance cash benefits (represented by a central coin-dispensing hand) leads to a scene of an abundant supermarket cornucopia and, p. 114 in the last vignette, the same kitchen apartment as before but now as the setting for a harmonious family feast: well-coiffed mother, mannered children, and father presiding, hands employed in carving the festive bird. This progression from domestic and urban disorder to order enables the middle symbolic strata in the mural above, which depicts, in highly stylized form, seated father and mother figures cradling their child with “joyousness.” In the topmost frieze, cubic shapes, Nivola explained, could be read as an urban skyline or as “silhouettes of individuals of social importance,” either way symbolizing, atop the whole, “the massive image of modern, authoritative, responsible society.”78 Thus, the layered grid of the mural narrates the self-production and management of the subjectivity, behavior, and identities of family individuals in the service of society.

The lobby’s other northerly wall, at the center of which is the Great Seal of the United States, is devoted to employment services, the other progressive postwar strategy of the American welfare state to promote subjectivity and agency. Here, the lower register narrates, Nivola explains in his printed description, the opportunities provided by employment services: from a generalized “work force” (a writhing mass of bodies, arms, legs, and hunched backs); to skills training (more-disciplined bodies, tools, and factories); to the key, central image of clasped hands symbolizing “the cooperative exchange between the employer and employed,” or between capital and labor; then proceeding to paid, productive work (three stolid figures enmeshed in machinery); and, ultimately, the leisured enjoyment of the fruits of employment (a sprawl of figures free of labor, no bent backs).79 This narration on the lower level of the employment services mural enables the scenes in the strata above: in the middle register, highly stylized figures of agricultural and industrial workers with plants, tools, and an American flag, and then the topmost geometric frieze symbolizing “social harmony.”80

Figure 15 Costantino Nivola. “Employment Service” mural in Hurley Building lobby, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1969. Nivola’s murals achieve a purposeful, explicit narration of the postwar American welfare system, mirroring the system’s bifurcated federal and individual state administration, as well as its postwar strategies of providing cash benefits and subjectifying services. Nivola’s murals underscore, too, the system’s social and ideological roles, reproducing existing relations in a patriarchal, white, capitalist society. His optimistic, conventional presentation of American life is continuous with the public mural projects of the 1930s federal p. 115 New Deal. Nivola’s scenes privilege male workers as family breadwinners, inscribe traditional gender roles, exclude nonwhite citizens, and valorize harmonious domestic life, consumption, and leisure as civic activities, leaving rulership to the leaders above. Nivola’s murals thus illustrate sociologist Nikolas Rose’s conclusions about subjectivity in liberal, capitalist society—the “governing of the soul”—where “each normal family will fulfill its political obligations best at the very moment it conscientiously strives to realize its most private dreams.”81

Costantino Nivola. “Employment Service” mural in Hurley Building lobby, Massachusetts State Service Center, 1969. Nivola’s murals achieve a purposeful, explicit narration of the postwar American welfare system, mirroring the system’s bifurcated federal and individual state administration, as well as its postwar strategies of providing cash benefits and subjectifying services. Nivola’s murals underscore, too, the system’s social and ideological roles, reproducing existing relations in a patriarchal, white, capitalist society. His optimistic, conventional presentation of American life is continuous with the public mural projects of the 1930s federal p. 115 New Deal. Nivola’s scenes privilege male workers as family breadwinners, inscribe traditional gender roles, exclude nonwhite citizens, and valorize harmonious domestic life, consumption, and leisure as civic activities, leaving rulership to the leaders above. Nivola’s murals thus illustrate sociologist Nikolas Rose’s conclusions about subjectivity in liberal, capitalist society—the “governing of the soul”—where “each normal family will fulfill its political obligations best at the very moment it conscientiously strives to realize its most private dreams.”81

Nivola’s presentation of the American welfare state’s character is exceedingly rare in the history of art, if not unique. I know of no other artistic representation of the system. Its location, however, in a lobby intended primarily for DES staff means that Nivola’s depiction is obscure to a wider citizenry using other building entries to receive their benefits and services. Eclipsed, too, in Nivola’s representation of the American welfare state’s mechanisms are the very conditions that produce the problems of unemployment, poverty, and instability in a capitalist society. For example, the clasped hands in the employment-service mural symbolize an idealized harmony between capital and labor, rather than the real, dynamic tensions that produce boom-and-bust cycles of overproduction, disinvestment, and unemployment, which no amount of worker retraining and subjectivity can mitigate. The scenes of happy family and work life reinforce the social sorting of U.S. welfare-state policies, which from the 1930s onmade lesser citizens of women, nonwhites, agricultural workers, and those outside traditional family structures. Thus, in both its balanced formal composition and idealized content, the murals elide the historical tensions within the American welfare state’s development: the difficulties of integrating an inherently fragmented and decentralized system; the contradiction of attempting to enhance clients’ subjectivity through bureaucracy; and the problems of perception and misrepresentation that vex the American welfare state.

Rather than the murals’ pictorial imagery, it may be the building’s p. 116 spatially and temporally dynamic, lived-in architecture that more wholly represents the contradictions within the American welfare state and society. This is not a matter of the architects’ deliberate intent; rather, it becomes apparent when the State Service Center’s architecture is read allegorically. Its design, process, and reception present extended, complex metaphors for issues of subjectivity and representation and, above all, the dialectic of integration and individuation that is one of the U.S. welfare state’s abiding tensions.

RE-PRESENTING THE WELFARE STATE

This article’s opening questions about welfare-state differences, culture, and futures can now be framed by this architectural allegory of the system’s historical development. First, the American welfare system’s identity lies in its dialectic between, on the one hand, a heterogenous localism and, on the other hand, impulses toward integration and standardization that an ascendant postwar U.S. federal government favored. This integrative agenda has its architectural corollary at the Massachusetts State Service Center, with its consolidations of program and plan, its monolithic concrete, and its unifying monumentality. But this integrative effort had unintended architectural consequences: an inward-facing plan and off-putting concrete gigantism that together distance citizens even as the whole seeks to incorporate them into the system. Architecture as allegory helps us apprehend the benefits and costs, the inherent and perhaps unresolvable contradictions between integration and decentralization in the making of the American welfare state and its citizenry.

The American welfare system’s historical midcentury pivot to services is also narrated architecturally at the Massachusetts State Service Center in the subjectivities intended to be produced by the building’s ornamental curves and concrete textures. The turn to services, told through design process, form, and reception, is a story of individuation and subjectivity sitting uneasily, unapprehended, and unappreciated within an overall, systematic structure that they cannot fundamentally alter. Architectural allegory asks us to consider whether an individual subjectivity can ever be produced within a bureaucratic system.

These representational aspects of the Massachusetts State Service Center’s history and design indicate that culture does matter in welfare-state studies. No account of a welfare state should ignore how people perceive and feel about the system, what they think they see and hate in its manifestations (including its architecture), and how cultural products such as Nivola’s murals and the State Service Center’s architectural design affect a welfare state’s ability to reach and create its citizenry. The murals and building continue the New Deal state’s pictorial and big-project tactics, but now coincident with p. 117 new postwar mass media and culture. To return to my opening vignette at Harvard Stadium, for decades television and football have produced together a vivid American subjectivity—interposing the individual and the collective at levels of team and mass audience. But, for the American welfare state, the Massachusetts State Service Center’s architecture allegorizes what has been a much more convoluted and contentious intercalation of individuation and integration.

Matters of representation connect finally to the question of welfare states’ futures. Today, social and economic inequality is frequently connected to weakened welfare states, a product of decades of neoliberal privatization and austerity, as well as antagonistic cultural representations. But might different representations of the American welfare state—including its architecture—facilitate more nuanced views of the system’s history and promote positive outlooks toward its future? An architectural history of the Massachusetts State Service Center that is not simplistically about Rudolph or brutalism but instead sees the building as enacting and participating in the American welfare state’s historical complexities and subjectivities might, at one level, help guide state officials in their ongoing stewardship. Should the building complex, which sits on a large, valuable downtown site, be rejuvenated and maintained, or sold, adapted, and perhaps even demolished for private profit, as Massachusetts officials in late 2019 propose for the Hurley Building?82 What would such choices say about the state’s social commitments to its resources and citizens’ well-being? If instead the complex is maintained, what architectural significances might be prioritized (the subjective textures and curves, its public porosity, Nivola’s murals), and what aspects modified (a Cambridge Street entrance, at last, to moderate its off-putting affect)? Finally, at larger political and social levels, could re-presenting the history of welfare-state architecture as an allegory of systemic tensions and contradictions help produce a more nuanced consideration of welfare states themselves? If we understand, through architecture and allegory, welfare states’ struggles between integration and decentralization as well as the difficult production of subjectivities within systems, then we can replace terminal judgments with open-ended imaginings of welfare states’ potentials. Re-presenting welfare-state architecture, in all its complexities, might then play a role in reinvigorating understanding and commitment to the social rights, benefits, and relations that democratic governments necessarily owe citizens navigating a dominant capitalist order.