p. 21

An Introduction to Warhol v. Goldsmith

Amy Adler

In May 2023, in Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith, the United States Supreme Court issued a major copyright decision on “fair use” in the visual arts.1 It was the Court’s first ruling on the fair use of creative works in twenty-nine years and its first-ever ruling on fair use and visual art.2

The case involved sixteen works Andy Warhol created in 1984 based on a copyrighted photograph taken in 1981 of the musician Prince by the well-known rock-and-roll photographer Lynn Goldsmith. While Goldsmith had disputed Warhol’s right to create these works, and by implication the rights of museums and collectors to display or sell them, the Supreme Court decided the case on a much narrower issue involving commercial licensing. Ultimately the Court affirmed by a 7–2 decision a lower court judgment favoring Goldsmith on the issue of fair use.

Fair Use

Fair use is a defense to a claim of copyright infringement.3 Copyright grants creators a limited monopoly over the use of their works, but fair use acts as a check on that monopoly. The doctrine is designed to balance the rights of creators to control their works against the rights of the public and other creators to access and build on them to create new works. As the Supreme Court explained, fair use guarantees “breathing space” for future creativity within the confines of copyright.4 Quoting the copyright clause of the U.S. Constitution, the Supreme Court explained that “some opportunity for fair use of copyrighted materials has been thought necessary to fulfill copyright’s very purpose, ‘[t]o promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts.’”5 The fair use doctrine thus permits and even requires courts to “avoid rigid application of the copyright statute when, on occasion, it would stifle the very creativity which that law is designed to foster.”6

The fair use defense to a claim of copyright infringement has a long history in common law (i.e., law derived from judicial decisions p. 22 rather than from statutes). First distilled by Justice Joseph Story in the mid-nineteenth century, fair use is now codified in the Copyright Act of 1976, which provides that the “fair use” of a copyrighted work “for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research” is not an infringement of copyright.7 To determine whether a particular use is “fair,” the Copyright Act provides an equitable, fact-sensitive set of four factors for courts to consider:

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.8

As the Supreme Court has made clear, these factors “set forth general principles, the application of which requires judicial balancing, depending upon relevant circumstances.”9

The interpretation of the fair use factors, though not their wording, changed dramatically in 1994. In Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, a case involving “Pretty Woman,” a parody rap song by the band 2 Live Crew, the Supreme Court introduced a new term, transformative, into its analysis of the first factor of the test, which evaluates the “purpose and character of the use.” The Court said the “[t]he central purpose of” an inquiry under the first factor must be to see whether a work is transformative; that is, whether it “merely ‘supersede[s] the objects’ of the original creation or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message.”10 The term transformative became pivotal in fair use cases, particularly in several high-profile art cases in the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. (The Second Circuit, which includes New York City in its jurisdiction, is no stranger to art litigation.) The question of whether works were “transformative”—whether they added a “new meaning or message” to the underlying work—became the primary battleground on which cases about the artists Jeff Koons and Richard Prince were fought.11 Warhol v. Goldsmith was fought on this same terrain as it worked its way through the lower courts. But the Supreme Court’s decision in this case changed the nature of the fair use inquiry.

The Warhol Facts and the Litigation Below

The Warhol case involved sixteen works Warhol created in 1984: twelve silk-screen paintings, two screen prints on paper, and two drawings, collectively called the “Prince series.” Warhol created the works after Vanity Fair commissioned him to make an illustration p. 23 for a story about the musician Prince. The magazine had licensed Goldsmith’s 1981 photograph of Prince for a one-time use as an artist’s reference, which it shared with Warhol. Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, Warhol used the image to create not only the Vanity Fair illustration but the entire Prince series.

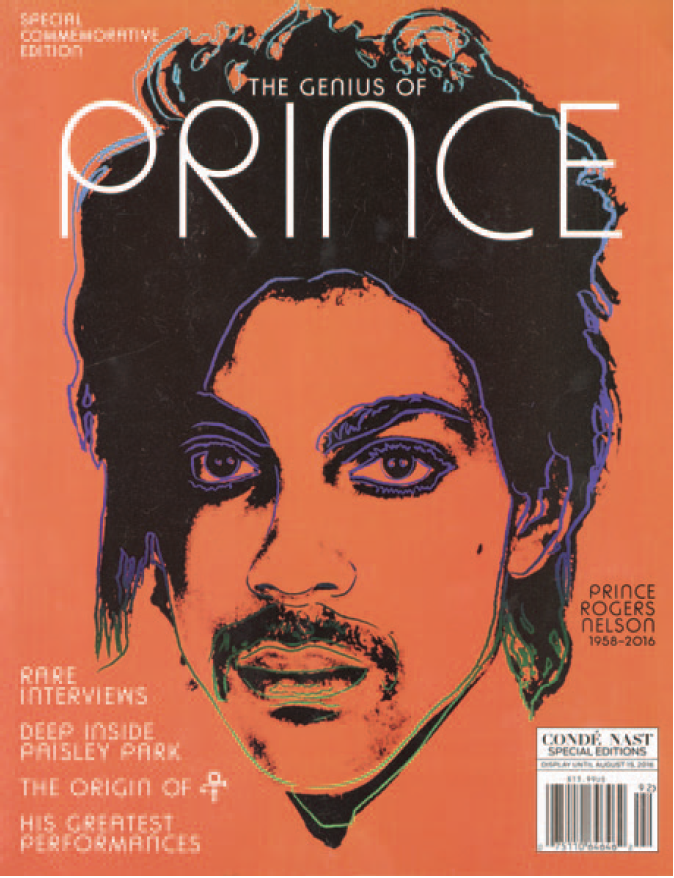

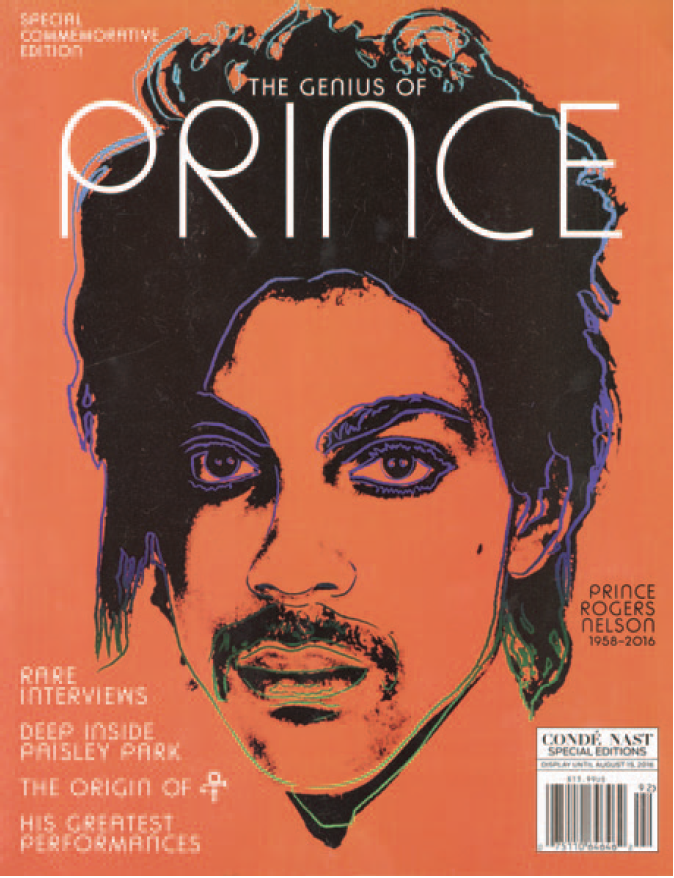

Figure 2 Andy Warhol, Orange Prince, 1984. Silkscreen on canvas. Reproduced on the cover of “The Genius of Prince: Special Commemorative Edition” (Condé Nast Special Editions, 2016).

When Prince died in 2016, the Warhol Foundation (now standing in the artist’s shoes) licensed one of Warhol’s silk screens, Orange Prince, for the cover of a special Condé Nast magazine commemorating the musician. Goldsmith saw this cover, learned of the Prince series, and notified the Warhol Foundation that she believed the series had infringed her copyright. The Warhol Foundation then sued Goldsmith for a declaratory judgment of noninfringement or fair use.

The district court sided with the Warhol Foundation, finding on summary judgment that Warhol’s sixteen works were transformative and that they constituted fair use under all four factors.12 The Second Circuit Court of Appeals reversed, finding that the Prince series works were not transformative and that all four fair use factors favored Goldsmith.

Andy Warhol, Orange Prince, 1984. Silkscreen on canvas. Reproduced on the cover of “The Genius of Prince: Special Commemorative Edition” (Condé Nast Special Editions, 2016).

When Prince died in 2016, the Warhol Foundation (now standing in the artist’s shoes) licensed one of Warhol’s silk screens, Orange Prince, for the cover of a special Condé Nast magazine commemorating the musician. Goldsmith saw this cover, learned of the Prince series, and notified the Warhol Foundation that she believed the series had infringed her copyright. The Warhol Foundation then sued Goldsmith for a declaratory judgment of noninfringement or fair use.

The district court sided with the Warhol Foundation, finding on summary judgment that Warhol’s sixteen works were transformative and that they constituted fair use under all four factors.12 The Second Circuit Court of Appeals reversed, finding that the Prince series works were not transformative and that all four fair use factors favored Goldsmith.

The Supreme Court Decision

The Supreme Court decided the case on much narrower grounds than the lower courts had. Whereas those courts had made their determinations of fair use for all sixteen works in the Prince series, the Supreme Court limited its ruling to a consideration of only one use of one work of the series: the 2016 licensing of Orange Prince for the cover of the Condé Nast issue created when Prince died. The court explicitly expressed no opinion about the other works or whether Warhol had been entitled to create the Prince series in the first place. Furthermore, the Court’s holding was confined to its evaluation of only one of the four factors that constitute the defense of “fair use” under copyright law. The sole question presented to the court on appeal was whether the first fair use factor, “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes,” weighed in favor of Warhol or Goldsmith. The Court held 7–2 that this factor favored Goldsmith. Justice Kagan, joined by Chief Justice John Roberts, issued a bitter dissent.

Despite the narrow scope of this decision, the Court’s opinion p. 24 made significant changes in the law of fair use.

First, it diminished the importance of an inquiry into “transformativeness,” one of the primary grounds on which the case had first been litigated, and instead stated that “transformativeness” was only a subsidiary aspect of a larger inquiry into the “purpose and character” of a use under the first factor. The key consideration according to the Court should be whether the uses of two works have a similar purpose rather than whether they have a different message or meaning. The Court determined that, in this case, Goldsmith’s portrait and Warhol’s Orange Prince both shared “substantially the same purpose,” which was “to illustrate a magazine about Prince with a portrait of Prince.”13

Second, the Court emphasized that the commercial nature of a use was relevant to understanding its purpose. Questions of transformativeness “must be weighed against other considerations, like commercialism,” which tends to dictate against a finding of fair use. As the Court wrote, “If an original work and a secondary use share the same or highly similar purposes, and the secondary use is of a commercial nature, the first factor is likely to weigh against fair use, absent some other justification for copying.”14

Third, a novel aspect of the decision was evident in the narrowness of its ruling. The Court stated that a fair use analysis might vary based on a specific “use” of a copyrighted work and that the same copying might be fair when used for one purpose but not another. This was a significant departure from previous fair use cases, which proceeded on the level of whether the work itself was fair rather than a particular use.

p. 25

Participants

Amy Adler, Emily Kempin Professor of Law, NYU School of Law

Lionel Bently Herchel Smith Professor of Intellectual Property Law, Faculty of Law, University of Cambridge

Susan Bielstein, executive editor for art etc., University of Chicago Press, retired

Johanna Burton, The Maurice Marciano Director, Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Los Angeles

Martha Buskirk, professor of art history and criticism, Montserrat College of Art

Noam M. Elcott, associate professor of art history, Columbia University

Jane Ginsburg, Morton L. Janklow Professor of Literary and Artistic Property Law, Columbia Law School

Branden W. Joseph, Frank Gallipoli Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art, Columbia University

Joan Kee, professor of the history of art, University of Michigan

Liz Linden, artist

Rebecca Tushnet, Frank Stanton Professor of the First Amendment, Harvard Law School

Graeme Williams, photographer and YouTube channel host

Winnie Wong, associate professor of rhetoric, University of California, Berkeley

p. 26

Roundtable Discussion15

Noam M. Elcott: Before we discuss Warhol, can we discuss Warhol? Commercialism seems to have taken center stage in the Warhol decision, and all sellable art seems to be potentially understood as commercial. That was a central question for Warhol and pop art in general, but is all art equally commercial? Are commercial distinctions between early Warhol, late Warhol, and Warhol Foundation licensing relevant for the law or for art history?

Branden W. Joseph: In considering this question, I thought, “When do art and law meet?” Much of the time, although not always, they seem to meet when it’s a question of commercialization; that is, when there is, or someone feels there is, money lost or a profit to be made. We can discuss some other examples, but I think it’s noteworthy that it’s precisely at the intersection of art, commercialism, and illegality that Warhol’s work functioned, and that’s part of what made it important. More so than most pop art—all of which, of course, operated at the intersection of art and the commodity, or commercialism, in an overt although not entirely unprecedented manner—Warhol’s work also thematized illegality. This he did most notably, perhaps, in Thirteen Most Wanted Men (1964), which he produced in the context of the crackdown on homosexuality and other forms of illegality around the 1964 New York World’s Fair, as Douglas Crimp, Richard Meyer, and others have noted.16 Yet, he also—if not in that instance, in others—sometimes courted and encountered the police and the law more directly. Not only when he was threatened with lawsuits for the use of photographs—he was threatened with lawsuits by Charles Moore for the unfortunately titled Race Riot series of paintings, which actually depict African-American Civil Rights protesters being attacked by the police; by Patricia Caulfield for the Flowers series; and by Fred Ward for one of the Jackie pictures (for all of which, I think, I could make far stronger arguments for transformative fair use than the Prince series)—but also in his films. So, for instance, Warhol’s notoriously named film Blow Job (1964) notably didn’t show its provocative titular action because it seems to have been part of a cat and mouse game with the New York City Police. It was assumed that the film Blow Job was going to show a blow job, but if the police came to shut it down, they would discover that the film didn’t show the act, but only the reaction shot. Warhol was potentially courting censorship, a certain type of police intervention, and then thwarting it. Warhol had, in fact, already had a film seized by the police, apparently partially by mistake. The police seized Warhol’s film Jack Smith Shooting Normal Love (1964) along with Jack p. 27 Smith’s notorious film Flaming Creatures (1962–1963), even though Warhol’s movie wasn’t in the least provocative.17 Also, at the end of the 1960s, Warhol’s Blue Movie (1969), which depicted an act of heterosexual intercourse, pushed then-transforming definitions of obscenity and pornography and actually went to trial in 1969. So, the intersection of art, commercialism, and illegality was at the center of Warhol’s work in the 1960s. I think this is potentially important to reflect on, or at least to consider, in order to complicate some of the ways that Warhol’s work, not just the Prince series but the long history leading up to it, was talked about in the context of the case.

Amy Adler: Regarding the ’80s Warhol, I’d like to think about whether the Court got this exactly right in viewing Warhol through the lens of commerciality, given that we were dealing with a 1984 series of works. Was the Court in some way correct? Also in terms of temporality, it strikes me that lawyers, law professors, and judges seemed to be seeing Warhol’s work not as it was in the 1980s, and not even as it was in the 1960s, but rather from an ahistoric present in which we take Warhol completely for granted. The lower court in this case had discussed Warhol as just a “style.” During the litigation of the case, lawyers frequently discussed these works as just “Warholization” of the photographs.

Joseph: I want to maybe caution us about thinking about a 1980s Warhol. There’s often a surreptitious value judgment made when talking about the ’80s Warhol versus, say, the ’60s Warhol. Noam pointed me to an essay by Ben Davis, who made something of this argument.18 If we want to talk about the distinctions and/or continuities between the 1960s and the 1980s, I think Neil Printz, who is the editor of the catalogue raisonné, did a quite good job in his court declaration talking about the transformations that Warhol’s technique underwent over that time. There also used to be in Warhol scholarship an idea that there was a very strict division between the 1950s Warhol and the 1960s Warhol. Later, when some of the repression of Warhol’s sexuality started to erode, people significantly reevaluated and valorized the overtly homoerotic work of the 1950s.

Toward the end of “Saturday Disasters,” the essay written in 1987, Tom Crow—who was, with Printz, one of the two principal expert witnesses—implied that Warhol was not so interesting after 1964. He says, “the clichés began to ring true.”19 Whether engaged by the Warhol Foundation or not, I don’t think that Tom would still hold that to be the case.

Davis argues that Warhol from the 1970s onward is bad and commercial, and he specifically cites Interview magazine. But I can p. 28 give you instances of artists in the early 1970s who regarded Warhol’s abandoning of the high art status of the painted canvas for the publication of Interview as entirely radical.20 It authorized them to use correspondence, photocopied mailers, fanzines, and other types of affordable, mass-reproduced, and mass-distributed materials with different relationships to artistic production, distribution, and fandom. The fact that Warhol went from depicting celebrities on expensive canvases to interviewing celebrities in a newsprint publication that anyone, in a sense, could buy: they saw that as completely progressive.

If we think about works closer to the 1980s, the Oxidation Paintings of 1977–1978 are generally considered to be important and interesting works. The Rorschach series of the mid-1980s are also generally considered to be provocative pieces that intervened against the contemporary rise of neo-expressionist painting. Certainly, the Dia Art Foundation would argue that the Shadows of 1978–1979 were a significant production that Warhol executed on the cusp of the 1980s. They bought the entire series and retained their original full-gallery installation as an environment for the way it challenged issues like “high” and “low,” art and design (Warhol called them “disco décor”).21 So, as the scholarship is moved forward by Printz and others, like Uri McMillan, who’s done interesting work on Interview, I wouldn’t be surprised if we have a substantial revalorization of what Warhol was doing in the 1980s.

The Prince series seems to be different because it starts as a commission. Yet, even after Warhol moved into pop, he did a commission for TV Guide in 1966, which probably used a similarly licensed image. He also did commercial work for Harper’s Bazaar depicting cars and for the Container Corporation of America in the style of pop paintings. He made a TV advertisement for the Schrafft restaurant chain in 1968. So, Warhol’s imbrication with licensing, work for hire, and commercialism arguably continued throughout his career, potentially up through the 1980s.

With regard to the relationship between the 1960s and the 1980s, I’ll just point out one last thing. Although Crow was initially skeptical of the work Warhol made after the Death and Disaster series of 1963–64, his perspective started to change, perhaps as early as his book The Long March of Pop. In his testimony for the court, Crow characterizes Warhol’s Prince portrait as in a differential relationship to the portrait of Michael Jackson with a light-yellow background done for Time magazine in 1984.22 Crow sees Warhol’s portrait of Jackson as a certain archetype against which his portrait of Prince is a different archetype. This is very similar to what Crow argues about Warhol’s 1960s portraits of Marilyn Monroe versus those of Liz Taylor. The first is a bright, “golden haired” icon that’s mythologized in a certain way; the second, a dark-haired icon p. 29 that’s mythologized in a different way.23 He brings that same reading to the pairing of Jackson and Prince. So one of the things that Crow argues in his expert testimony is that, with the Prince series and its relationship to the Michael Jackson portrait, Warhol comes to reconnect with what he was doing two decades before.

Elcott: Let’s pivot to the Warhol decision, which has been criticized from a number of angles, especially, of course, from the Warhol camp. In what ways is the decision successful?

Jane Ginsburg: The decision was successful in stemming the excesses of some lower courts with respect to the interpretation of the fair use doctrine, particularly the first factor, the purpose and character of the use, which is one of four. But many lower courts, in the name of “transformative use,” had taken the first factor to be essentially the entire doctrine. And then in an overenthusiastic interpretation of the Campbell v. Acuff-Rose decision, concerning a musical parody, some courts determined that, once the defendant’s work was transformative, because it gave new meaning or message to the copied material, then the first factor weighed in favor of the defendant.24 And if the new work was transformative, then it did not compete with the underlying work. So, the fourth factor tagged along with the first, and the second and third factors were pretty much ignored. This was a doctrinal mess. Has the Supreme Court successfully restored order? As to the first factor, maybe. The court has made clear that creating a new work that adds a “new meaning or message” does not suffice to make a use “transformative.” The court confronted the tension between transformative fair use and the exclusive derivative works right, which encompasses the right to “transform” the initial work. The court also emphasized the significance of the commercial purpose or character of the use, recalling Campbell’s sliding scale of transformativeness relative to commerciality. On the other hand, the court took the case only on the first factor. Frankly, I think the court should not have taken the case at all. But if it was going to take a fair use case, it should have taken the entire provision of section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Act. But because the court took only the first factor, there continues to be the risk that the four factors collapse into the first factor.

Rebecca Tushnet: The derivative works right gives authors rights to control translations, dramatizations, movie versions, and even toys based on their works. Derivative works often substantially transform the meaning of the original, so authors’ rights proponents warned that valuing mere meaning-transformativeness risked crushing the derivative works right. The Supreme Court heeded p. 30 these criticisms: a second author needs a reason—possibly compelling—to target a particular work for fair use, which puts a thumb on the scale for the first author. The majority highlighted that derivative works can also “transform” the original, rejecting any idea that “transforming” the meaning of the original would inherently favor fair use.

Yet the logic of the majority and the fair use cases the Court distinguishes indicate that transformative purpose—in which there may be no physical alteration of the work at all—is still safe—safer than artistically motivated changes (including satirical uses). Among other things, both the majority and the dissent reproduce the works at issue, and the majority even creates what is, by its own logic, an infringing derivative work to show the overlap between the works. The majority notices the problem but comments that its use is plainly fair: it is an evidentiary use, giving the images completely different purposes (and possibly meanings, but that’s secondary).

Joseph: The issue of transformation is interesting. Kagan, in her dissent, declared that Warhol effected an evident transformation from Goldman’s photo: “The result—see for yourself—is miles away from a literal copy of a publicity photo.”25 What interests me is the fact that, at the time of pop’s emergence, such transformations were not necessarily so evident. To go all art historical for a second, Leo Steinberg made this point explicitly in 1962 in a panel on pop art at the Museum of Modern Art, where he cited the criticism that “there is not sufficient transformation or selection within pop art to constitute anything new.”26 That’s a contemporary reception of pop art. Steinberg then notes, of himself, that he “cannot yet see the art for the subject … the subject matter exists for me so intensely” that he cannot see “whatever painterly qualities there may be.”27 Potentially more significant is that Steinberg also states, first, that this art (he’s quoting Victor Hugo on Charles Baudelaire) produces “a new shudder”; in other words, some sort of effect or impact. Second, he says that what the artist “creates is a provocation, a particular, unique and perhaps novel relation with reader or viewer.”28 The point is that Steinberg does not see the artistic transformation of the subject matter (transformation being one of the major issues argued in the Supreme Court case) but, nonetheless, feels it has some sort of impact on him, and in that he sees a new relationship between artist and viewer. That’s a contemporary critical reception of pop art, but Warhol himself, in his memoir POPism, similarly states about his early works that he “wanted to take away the commentary of the gestures.” He wanted to make “cold ‘no-comment’ paintings.”29 So that notion of transformation—which in Martinez’s oral arguments had to do with communication, communicating a new message—is problematized by the fact that the work p. 31 can have an effect apparently without any transformation.30 The idea that you could create an effect without an evident transformation or comment is, of course, foundational for appropriation art of the 1970s to now. Arguably, it produces the whole postmodern reception of pop, and thus, in my lay understanding of copyright law, fulfills the larger reason for granting certain copyright exceptions, which is that they are productive for culture at large. In this instance, the lack of evident transformation produced all sorts of revisitings and reengagements with pop and the production of what we now call “artistic appropriation.”

Martha Buskirk: Strategies that involve no evident transformation focus our attention on the frame within which the “no transformation” is taking place. Not only are new meanings generated by acts of appropriation, but shifting modes of perception over time can make certain forms of subtle transformation more readily apparent. I think that’s perhaps one of the hardest things to articulate in the legal context—how a frame of reference that is constantly moving or evolving will allow something to be seen in a different way.

Elcott: The question of framing seems especially important and difficult when tackling the intersections of art and law. The internal history of art is largely unknown to lawyers and judges, just as the internal history of law is largely unknown to artists and art historians. Given Branden’s observations on Warhol’s reception in terms of insufficient transformation, why would anyone ever argue for Warhol in terms of transformativeness? It makes almost no sense, except within a very narrow legal context (as discussed in the introduction to this roundtable). On the other hand, why did Warhol regularly paint a blank pendant canvas in the same color of the first silk-screened canvas? Judges can’t be expected to understand that. And yet, from the 1960s onward, Warhol’s monochromes became an important reference point for debates on abstraction and its opposition within the history of modern and postmodern art. Part of what makes this dialogue between art and law so challenging is that these two internal traditions—both, interestingly, often dubbed “formalist”—advance according to their own logics and of their own volition, such that their intersections seem incredibly idiosyncratic. If we study the history of modern art according to U.S. courts, it is a very idiosyncratic history. That can be explained, partially, because the art is driven by its internal volition and the law by its internal volition, and the two intersect only in the rare instances a dispute goes to trial.

Winnie Wong: In my reading of the opinion and the dissent, I find that they each present a very different picture of the world in which p. 32 artists operate. In the Sotomayor opinion, the art world is a commercial one. There are transactions, licenses, and markets. These ultimately underlie or prefigure interpretations, uses, and creativity. Goldsmith may not have been as “famous” as Warhol once upon a time, but she now deserves the same “exclusive rights.” The opinion opens with the biography of Goldsmith as artist in order to legitimate that equality. In the Kagan dissent, it is as though there is no market, Warhol’s “new new thing” is an example of creative progress above and beyond the limits of whether it was work made for “commercial gain” and whether there is a structural hierarchy of “artists” (low, high, elite, outsider, exhibited, licensed, etc.). A textbook history of art (i.e., the Western Tradition) lays the linear groundwork for honest “stealing” (see footnote 6 of Kagan’s dissent) and then “progress.”

The problem is that the market and the art world are obviously intertwined and yet not reducible to one another. Rarely do art historians interrogate how commercial practices or market interests operate in the practices and communities of artists over their lifetimes or in relation to one another. What causes one artwork or one artist to become viewed as “greater” or more valuable than another at some point in time? It probably isn’t copyright law, and it probably isn’t fair use. But copyright law has become the arena to battle over the seeming “injustice” that only certain people are honored by our institutions as “great” and valuable artists.

I saw a lot of commentary that made fun of Kagan for showing off that she had taken Art History 101. But these days, we cannot teach the Western Tradition as Kagan narrates it, because our students no longer allow us to sidestep questions of gender and racial inequality in art history, in museum institutions, or in the art market. It has become impossible to speak of “appropriation art” without being challenged to answer how it may (or may not) overlap with cultural appropriation, material dispossession, and cultural property. It is impossible to lecture on one artist without addressing the women artists who made very similar works but who have been forgotten. The structure of inequality in the art world is no longer seen as separate from the gender and racial inequality of American society at large. And our scholarly efforts to separate them conceptually and historically have become less and less convincing.

These inequities seem to extend to who makes up the litigants of prominent copyright cases or who has access to the burdens of suing or defending. On social media, copying accusations, apologies, and cancelations take place constantly, mostly between women. But the prominent copyright courtroom fights involving Warhol, Prince, and Koons have become proxy battles for misogyny, dispossession, and cultural memory—the very issues that our elite institutions have simply failed to address in a systemic fashion. So, for p. 33 me the problem is not copyright law, and it is not the boundaries of fair use. It is the public sense of injustice in the arts that gives rise to an alternative sphere of judgment.

Elcott: Further reflections on the decision from the legal scholars?

Adler: This decision changed the law of fair use by diminishing the importance of “transformativeness” and elevating instead the importance of determining the “purpose” of a work. But to me that creates a huge battleground over what level of generality we frame “purpose.” For example, as this case was litigated in the lower courts, Lynn Goldsmith’s lawyers argued that the Goldsmith work and Warhol’s works, including all his paintings, had the same purpose because they were both visual works. If that’s what we mean by purpose, then you can see that this new analysis threatens a vast amount of artistic borrowing. The Supreme Court took a narrower approach and analyzed just one use of the Warhol work and deemed the purpose in that instance to be a magazine illustration. So, it seems to me that battles over what level of generality you use to frame purpose could be the new interpretive problem for courts and not necessarily a solution to the interpretive battles that were fought about “transformativeness.”

Lionel Bently: Two observations. The first observation relates to Sotomayor’s focus on the fact that the Andy Warhol Foundation got $10,000 from Vanity Fair and Goldsmith got nothing, not even a credit. The court indicated that Goldsmith should get a fair share. That is, of course, what would be negotiated for ex ante. But, given the constraints for many artists on the practicality of ex ante licensing, a finding of copyright infringement (rather than fair use), changes the nature of negotiations. The artwork is already created. In these circumstances, copyright law can allow a plaintiff to extract much more than a fair share. A good example is The Verve’s “Bitter Sweet Symphony.”31 Of course, in the Warhol case, Vanity Fair had already used the image, so the only claim was damages (presumably based on a reasonable license fee, in which case Sotomayor gets what she expected). But others may not be so fortunate, not least purchasers of Warhol’s Orange Prince (or the other fourteen unlicensed Prince paintings).

The second concerns the importance of remedial flexibility. This flows from the first point but is more obvious coming from a jurisdiction that does not have a fair use doctrine [e.g., the United Kingdom]. Much appropriation art in general (and use of photographs particularly) is difficult to fit within the European Union’s closed list of exceptions/limitations on copyright. Case law has centered on what the photographer contributed creatively and whether p. 34 that appeared in the defendant’s work. Richard Arnold did a nice review of this a couple of years ago in IIC.32 But a finding of infringement can bring startlingly draconian remedies into play: not just damages based on a reasonable royalty but injunctions, accounts of profits, delivery up [for destruction]. The implications of the Warhol decision are worrying if courts do not possess real flexibility to fashion remedies that recognize the contributions of defendants.

Joan Kee: How do we deal with the fact that a lot of artworks move across jurisdictions that have very different ways of dealing with fair use. Lionel pointed out there’s no fair use defense in the United Kingdom. I’m also thinking about China, where fair use is very arbitrarily defined. And we have situations of artists having to contend with a system where law and policy—that line is so muddled as to almost be irrelevant. So how do we deal with globally mobile artworks?

Adler: I want to keep an eye on the doctrinal move that the court made in terms of commerciality, because even as we’re talking about the ridiculousness of making that commercial/noncommercial distinction in art, this case gives an increased salience to it in law. If we look back at the trajectory of the case law, in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose the court pushed back against a prior case that had given a presumption of unfairness to works that were commercial. Campbell said that the more transformative a use, the less commerciality matters. But Warhol reverses this trajectory and inverts the Campbell formulation, saying that the more commercial a use, the less important its transformativeness. So, considering whether a work is “commercial” has once again become super important.

Tushnet: I’m not quite as despairing—though I completely agree that commercialism plays a hugely outsized role in this decision. I think purpose still counts because the court drops all these references to things that were very commercial, including the ad for Naked Gun 331⁄3, one of the most “low culture” things you can imagine and also a highly commercial movie released in theaters around the country. And this is why they distinguished a case like Google v. Oracle, where Google’s making a billion dollars.33 So I don’t think it’s commerciality. Actually, I would say that the shadow side of this is the fact that courts have essentially ruled that anything that people litigate over is commercial. So, it’s actually a completely useless concept at this point, especially as lower courts have applied it, and they’ve therefore found it necessary to say, when you have a favored purpose, it doesn’t matter that it’s commercial.

p. 35

Kee: To what extent has this decision also disclosed some of these huge asymmetries of power? Ironically, and this goes to the criticism of the decision, has it also led to a situation where those who have the means to enforce their rights somehow are also able to avail themselves of fair use much more broadly than those who don’t have those same resources?

Adler: An accident of the case law may reinforce that impression, which is that the only artists who appropriate and the only artists who assert fair use defenses are the rich and powerful, the “Gagosian privilege artists.” The case law presents a distorted view because the artists worth suing are typically rich and famous. They are also the only ones who can afford to litigate these cases rather than give in, so the case law reads like a roster of big-name artists. Jeff Koons has been sued five times; Richard Prince has been sued three times. But what this leaves out are the cases that settle or get shut down at the cease-and-desist-letter level. I’m thinking, for example, of when the David Smith estate shut down work by the relatively unknown artist Lauren Clay, who was making arguably feminist reappropriations of David Smith’s macho sculptures. That’s not a reported case because Clay quickly settled in response to the Smith estate’s cease and desist letter. It’s an example of how these inversions of power happen without visibility.

Liz Linden: Wealthy artists will be able to defend their copyright and assert their fair use claims, whereas less wealthy artists won’t. And so we get this kind of stratified application of the law, which I agree is troubling; it’s deeply problematic.

Adler: What you’re talking about is what in First Amendment law we would call a “chilling effect.” Given the uncertainty of what constitutes fair use and the extraordinary cost of litigation, poorer artists may be unwilling to appropriate. Richer artists are the only ones who can afford to defend themselves.

Linden: Yes. The wealthier or more established an artist you are, the easier it is to claim your affirmative defense of fair use. Whereas those of us who are emerging, less well-known, or not bolstered by blue chip gallery money will find that we can’t defend ourselves. And that is an issue that applies on both sides, which I wanted to make abundantly clear. The other thing is that artists are trained within the conditions of art history, not case law. We learn to make our work and make meaning out of visual and other shared cultural elements, and we do that, explicitly or implicitly, contiguous with p. 36 all of the work that’s been made before. And, as a result, whatever judges and lawyers settle on as a test or rubric for when something is fair use is by definition in dialogue with legal theory and case law and not in dialogue with art history, the matrix of art itself. And so we will always—wherever the framework for fair use ends up in the future—look back at art history and see violations. But those violations are part of the fabric of art history that artists are looking at as they’re learning to express themselves through the language of art. If we agree that some derivative works are immensely communicative, that there is communicative value in appropriation, then we have to find a way to articulate where appropriation is prosocial as opposed to unethical. I don’t know how we’re going to define that line. I would desperately like to know where that line is, and I’m frustrated this case didn’t make that clearer. I’m not interested in making unethical work, but I see immense value in appropriation as a way to communicate critical insights about how the world is, by pointing to exactly how the world is through re-presenting elements of the world in my own work, and I know many, many other artists who do the same. And I’m super curious, Graeme, to know how you feel about this decision—if for you this decision is adequate and what you hoped for, or if you also wished that the case addressed more of the first-factor issues that it doesn’t speak to fundamentally.

Figure 3 Graeme Williams, “While Nelson Mandela was speaking to the crowd at the Sam Ntuli Stadium in Thokoza in 1990, children toyi-toyi (protest dance) below a police armored vehicle,” 1990. © Graeme Williams

Graeme Williams, “While Nelson Mandela was speaking to the crowd at the Sam Ntuli Stadium in Thokoza in 1990, children toyi-toyi (protest dance) below a police armored vehicle,” 1990. © Graeme Williams

Graeme Williams: I took a photograph in 1990. It was when Mandela was speaking in a township outside Johannesburg. The image shows a group of young kids doing a dance called toyi-toyi. It was a sort of rebellion against the power structures of the apartheid government. The image juxtaposes the kids doing the dance and a group of apartheid policemen looking down almost dejectedly on this. At the time, it was just another image in a whole series of images. It was a period of ongoing transformation before Mandela became president. And the image gained prestige over time because it came to be seen as an iconic representation of when power shifted from the apartheid government to the African National Congress. It has been published in magazines and books and has been exhibited widely. Obviously, I didn’t have all that information in my head at the time. But then it took on this role as a symbol of transformation and in the lead-up to the Obama-McCain presidential election. Either Barack Obama or his team chose my image to represent his worldview. And it was used in a double page in Newsweek. And then fast-forward to 2018. I was exhibiting at the Johannesburg Art Fair and so was Hank Willis Thomas.34 I happened to walk into a gallery space called The Goodman and saw my image; or rather, a slightly greyed-out version of the original image. Very little had been done to transform the photograph. It was a real shock. And it p. 37 took me a while—in fact, I just left, went out and had dinner on my own and thought, how do I react to this? A very good colleague-friend-mentor, David Goldblatt, was always someone I turned to for advice, but he had passed away a few months earlier. So, it was one of these moments where it was “okay, I’ve got to kind of man up in this situation.” I started posting about the appropriation on Facebook, and normally if I get two or three likes from a Facebook post I’m lucky. In this case the post went viral, and I was getting a thousand interactions per hour from the photography community throughout the world. It just grew and grew and grew. The response was overwhelming. I found it amazing that so many people around the world really felt passionate about what was going on, and the fact that this image was being used became irrelevant. It was the fact that an established, well-funded, well-exhibited artist could feel it was his/her right to appropriate an image and attach a $36,000 price tag without even consulting with me.

Wong: An element in Graeme’s story that we see repeated often in public condemnations of copying is the price tag of the works. There is an implicit judgment that $36,000 for a work is immoral, especially when it is compared with a licensing fee of, let’s say, $100. The prices that are reported imply a set of categories of art or, let’s say, a classification of artists, even though those categories seem to have no clear boundaries when everyone is, theoretically, treated equally as an “artist.” So, the price tag gets imprinted in the public discourse as an implicit moral or ethical judgment above and beyond any legal or artistic opinion, even our own.

Kee: The distinction between what is legal and ethical is very much a moving boundary, especially in art worlds lubricated by powerful commercial and institutional forces that operate according to their own unwritten laws. If you use an image of a work by certain artists, for example, you have to go through their estate or a foundation. And if you don’t go through these entities, you may not p. 38 necessarily be blackballed—it’s way too crude and fraught a term—but in other ways your movement in the art world might be inhibited or precluded. So, this is also just another question that we might want to think about. What is legal in one context may not be acceptable or desirable in another.

Elcott: Of the many hundreds or thousands of uses prior to the appropriation by Hank Willis Thomas, what percentage, roughly, were licensed?

Williams: Almost all of them were licensed at a very low rate. Until the end of last century we South African photographers who had been on the anti-apartheid side of the struggle—we were very supportive of any organization that was working to end apartheid. So, we weren’t very strict about usage fees. The African National Congress used to copy our pictures and sell them, and we were quite happy for that to happen, because we understood there was a broader movement working toward social change. Post-1994, when South Africa was a democracy, newspapers, magazines, galleries would be required to gain permission and usually pay a small fee for usage.

Ginsburg: Did you get name credit for all of those uses?

Williams: Always. But it was my choice. I could choose whether I wanted the image used or not. Nobody had the right to use my photograph or anyone else’s without consultation. It was contractual—one would normally have to sign a contract for usage.

Bently: The court repeatedly invokes the need for a film producer to obtain permission from a novelist whose work is being adapted for a film. It argues that this shows that transformation alone is not enough for fair use. However, it also could highlight a key consideration in fair use: whether prior licensing is culturally, institutionally, and practically feasible. In mainstream film (on the whole), such prior licensing is normal, given the huge budgets and organization. But fair use becomes important where such prior licensing is not practical (as the court at least recognizes for target parody). In the Warhol case, licensing was clearly practical (as it occurred for the first Vanity Fair issue in 1984). Other aspects of Warhol’s m.o. might also have reinforced the expectation that he or the foundation was an actor who might reasonably be expected to obtain licenses. Where does the court’s reasoning leave others for whom such a possibility is less realistic?

So, I put the broad question in these terms, and I think this is entirely lost in the decision: Would the requirements of ex ante p. 39 licensing prevent the production of this transformative work? And if it would, then that’s a situation in which one should find that the purpose and character of the use (the first fair use factor) is in favor of the defendant.

Linden: This is superimportant and not nearly visible enough. Many artists who have significant representation and show in multiple galleries still are fairly hand to mouth in terms of how they support themselves, how they subsist. For that matter, the vast majority of artists have no representation at all and certainly none of the structure that you’re speaking of to operate some sort of licensing agreement or, for that matter, to license—or afford to pay to license—the work of others. It’s just not viable. So, when I contributed to the amicus brief for the Supreme Court Warhol case, along with a number of other artists, including Hank Willis Thomas, I gave the lawyers a number of statistics that I thought were useful. Do you mind if I just read them out loud? NEA datasets say that nearly 2.5 million artists are in the U.S. labor force. And they give the average income as $52,800. An estimated 333,000 artists or workers have secondary jobs as artists, so that encompasses those of us who, for example, teach to support ourselves. Of course, there’s also all sorts of sobering information about how hard it is to be a woman artist, an artist of color, how much more challenging it is to support yourself in that context. The Art Basel Market Report from 2021 says that fewer than 5 percent of galleries make up more than 50 percent of contemporary art sales. So, the pointy end of the art world is extremely, extremely small. In another index of that lopsided nature of the art world, the Art Newspaper reported that one-third of solo exhibitions in U.S. museums are by artists represented by the same five galleries. So, you can say, well, this artist is doing very well, they’ve got a lot of dealers representing their work, and so of course they can pay licensing fees rather than invoke fair use, but even that representation doesn’t mean that they’re actually doing well in terms of the stratosphere of the art world. It is no small thing to support yourself as a working artist in the U.S. or anywhere else for that matter. And I think it’s just very easy to debate these issues from a legal perspective as simply concepts about creativity and use, but, at the practical level, my feeling is that very many of the people working on these cases, lawyers and certainly also Supreme Court justices, don’t actually know any artists or have a sense of how precarious most artists’ lives actually are or why artists might choose to continue making their work in the face of such precarity.

Buskirk: It’s actually quite striking that the court came down with a decision that’s going to have an incredibly far-reaching impact on p. 40 art without any substantive discussion about art as such in the majority opinion.

Ginsburg: I’m not sure that this decision really is going to make that much difference or be hugely important for the art world. Particularly because the court did not address what to do about the fine art iterations of the Warhol image. The court deliberately left that alone. Justice Gorsuch suggests that those iterations can continue to be exploited in the fine art context. That was also Judge Jacobs’s approach in his concurrence in the Second Circuit’s decision in the Warhol case. So, I think we’re going to be treating mass-market exploitations differently from art-world-confined exploitations. I don’t know that this is going to have a huge impact on the art world if we limit the art world to the exploitation of works in a fine art context and not merchandising, not licensing for magazines, and so forth.

Kee: To follow up on Lionel’s point, one possibly good thing about the Warhol decision is that it might incentivize anticipating what issues might come up as opposed to figuring out how to control the damage after a situation happens. I agree completely with Jane that this is a case that should never have gone to the Supreme Court. That said, how do we move forward? What was striking to me about Graeme’s experience with Hank Willis Thomas is how Thomas tried to handle this entire predicament after the fact. The situation becomes messy because it’s not necessarily just about works being altered but about actual feelings. One has to account for how fellow artists might respond to what they perceive as others taking or using part of their work. How can this be managed beforehand in such a way that it doesn’t devolve into this kind of chaotic, time-consuming, and frankly unnecessary situation?

Buskirk: Graeme, I can absolutely sympathize with the disconcerting experience of encountering your photo quite directly appropriated within a work that also happened to be on sale for a pretty penny. But you also talked about a longer history of the photograph gradually gaining iconic status based on the meanings that many people invested in the photo over time. You mentioned that you have been very generous with licensing, and for many types of uses a fee would clearly be appropriate. But my point of resistance concerns the question of control over interpretation via the licensing process and potential limitations on responses to an iconic image outside such agreements. The literal give-and-take at the basis of fair use can prompt resistance, particularly if strategies of quotation or transformation are accompanied by disparities in price or status. Yet support for this principle is essential in a world filled with p. 41 ownership interests. If the message to artists is to protect themselves by attempting to secure a license for any response to a preexisting image, the upshot will be an increasingly anodyne culture of complicity rather than critical messaging.

Elcott: Hank Willis Thomas had an interesting comment in artnet News that I think warrants quotation:

“I can see why he [Graeme Williams] would be frustrated,” Willis Thomas told artnet News. “He said to me that he didn’t feel like I had altered the image enough. The question of ‘enough’ is a critical question. This is an image that was taken almost 30 years ago, that has been distributed and printed hundreds of thousands of times all over the world. At what point can someone else begin to wrestle with these images and issues in a different way … much the way that people would quote from a book?”35

It’s a messy statement, no doubt, not written by a lawyer. But can we begin to unpack the issues raised, because I believe they’re significant? The problem here, I would venture, is not that one side is wrong but that both sides are right.

Williams: My response would probably mirror what one writer wrote; namely, the level to which Hank Willis Thomas transformed my photograph and made it his own artwork was like a writer rewriting the first and last paragraphs of War and Peace and calling it his own. I thought that was quite an apt response. It seemed to me that what he had done was very lazy appropriation. And when I initially spoke to Thomas, he didn’t actually know the history of the image. He just chose it because he liked the image.

Linden: How responsible are we as consumers of visual culture, though, for knowing the history? I mean, the rabbit holes of referencing go very, very deep with many of the iconic elements of culture. To go back to Martha’s statement, your image, Graeme, has become so powerful that it’s become iconic, which is obviously a testament to the importance of your work. And yet, because it’s circulated so widely and become so iconic, it’s inevitable that it’s going to circulate beyond the boundaries of places where people will get that history that you gave us. And that’s an inevitable part of how visual culture works and also, ultimately, appropriation. That’s how we get into the problem that Winnie already mentioned with cultural appropriation and images and other elements being decontextualized entirely and then recycled in ways that are offensive, even. As for the question of how much referencing comes along with the original—I don’t have any answers to it. But I don’t p. 42 know that it’s realistic, in a broad sense, that we can expect every consumer of a visual document to be able to be in touch with all the specifics of where that document appeared first and why it was made and where it appeared after and next and so on.

Williams: No, I don’t feel that’s relevant at all. I feel that whether an image is iconic or not has no bearing on copyright. But to refer back to the earlier question about when an image becomes iconic, do you then lose the rights to the photograph? Should one step aside as the original author? The sale of my images has contributed a lot to my income, and I don’t earn very much money. So, I don’t really care whether something becomes iconic. There have been a few moments when I’ve got things right and achieved a good image. These photographs are incredibly valuable to me.

Ginsburg: There’s something perverse about saying that, when a work becomes iconic, when it becomes very successful, it effectively loses its copyright. That is not a position that courts by and large have endorsed. On the proposition that appropriation art is upsetting power structures, I have to query that assertion: when appropriation artists take from lesser-known artists, how are they upsetting power structures? Joan made this point in her written statement, where she called out the tendency of, at least, the Warhol Foundation, to say, in effect, “What’s yours is mine, and what’s mine is mine,” and therefore, Ishmael Reed cannot appropriate or use a Warhol image.

Susan Bielstein: By way of a historical perspective, I’d like to mention that we wouldn’t be fretting over the copyright status of most “iconic” images if we had a robust public domain, which would mean shorter copyright terms. The original copyright term in the U.S. was only fourteen years with a possible one-time renewal. The short term was meant to move works quickly into a freely shared culture and as an impetus to further creation. Today, copyright lasts for generations: an author’s lifetime plus seventy years. Works for hire are protected for ninety-five years from first publication or 125 years from creation.

Elcott: In the SCOTUS decision and even in the varied amicus briefs, there was an extremely superficial treatment of artistic appropriation. I believe we can make a distinction between appropriation art, a specific movement that dates roughly to the late 1970s and ’80s and remains influential, and the larger question of appropriation, which, through various names and under different p. 43 guises, is endemic to all art-making and is a central feature of modern art in particular. I believe one can ask whether Warhol was an appropriation artist. I think Sherrie Levine is an appropriation artist. Was Warhol? I think art historians could disagree on this matter. And plenty of people would say, no, it’s a misnomer to call Warhol an appropriation artist. So, the first question is, what are the art-historical stakes for appropriation art versus artistic appropriation? Is that an operative distinction? A salient distinction? And then a second question would potentially map that art-historical distinction onto what has become an important legal distinction—which remains firmly in place in light of the Warhol decision—between parody and satire. Parody targets a specific work. The work can be fairly appropriated, according to the courts, to perform the parody. The classic example is the 2 Live Crew knockoff of “Pretty Woman.” Without roughly the same sound and many of the same words, it would not be a parody. And that, of course, is entirely true of Sherrie Levine’s work as well. You can’t make After Walker Evans (1981) without citing Walker Evans. Satire, which doesn’t target a specific work and instead aims at sociocultural mannerisms more generally, is granted a much shorter leash by the courts. Is appropriation art parody and artistic appropriation satire? Of course, even with artistic appropriation and satire, artists still want, for good reason, to cite specific logos, specific photographs, specific advertisements, because that specificity carries meanings—aesthetic, political, ethical—that can’t be distilled by some abstracted generalization. Warhol is exemplary here: it mattered whether he used Coca-Cola or Campbell’s Soup or General Electric, even if those works were not quite parodies.

Rebecca, you have noted that in jurisdictions outside the U.S., the distinction between parody and satire, and also pastiche, is not sharp, that they’re in fact grouped together. Can you elaborate and help us denaturalize this perhaps uniquely American obsession with the distinction between parody and satire?

Figure 4 Walker Evans, Interior of miner’s shack. Scott’s Run outside of Morgantown, West Virginia, July 1935. Gelatin silver print.

Tushnet: Sure. So, first of all, these other jurisdictions tend to just list parody, satire, pastiche, so that you don’t have to do the interpretive steps to distinguish them, which is more consistent with the formal doctrine that courts aren’t good at interpreting art. In particular, the distinction between parody and satire is actually incredibly manipulable from a legal perspective, because it is always available to someone to say, well, this isn’t really a parody because either the thing that you’re criticizing isn’t really in there, so you’re just picking on it to get attention, or, in fact, it was already totally clear, so there’s no point in you picking on it, and you’re not actually saying anything useful. This shows up in things like Lo’s Diary, where, despite the historical record of people treating Lolita p. 44 as really what Humbert Humbert says she is, when Lo’s Diary presents her as an actual sexual abuse victim, some people say that was already clear, the author of Lo’s Diary was not doing anything important and just ripping off Nabokov.36 So the distinction fits legal categories, in particular, extremely poorly. Before 1994, even U.S. court decisions tended to say that parody or satire is a favored purpose, precisely because there’s a larger move that the parody or satire is making that is extremely distinct from the underlying work. Let me bring this to Sherrie Levine. When an artist says they need to copy that picture to criticize that picture, the responding move is, “But you’re not actually saying anything about that picture; you’re saying something about Western photography.” And so there was no reason to pick on Walker Evans; you could have found someone to license and picked on them instead. That’s one of the reasons that the satire-parody distinction is so unstable.

Walker Evans, Interior of miner’s shack. Scott’s Run outside of Morgantown, West Virginia, July 1935. Gelatin silver print.

Tushnet: Sure. So, first of all, these other jurisdictions tend to just list parody, satire, pastiche, so that you don’t have to do the interpretive steps to distinguish them, which is more consistent with the formal doctrine that courts aren’t good at interpreting art. In particular, the distinction between parody and satire is actually incredibly manipulable from a legal perspective, because it is always available to someone to say, well, this isn’t really a parody because either the thing that you’re criticizing isn’t really in there, so you’re just picking on it to get attention, or, in fact, it was already totally clear, so there’s no point in you picking on it, and you’re not actually saying anything useful. This shows up in things like Lo’s Diary, where, despite the historical record of people treating Lolita p. 44 as really what Humbert Humbert says she is, when Lo’s Diary presents her as an actual sexual abuse victim, some people say that was already clear, the author of Lo’s Diary was not doing anything important and just ripping off Nabokov.36 So the distinction fits legal categories, in particular, extremely poorly. Before 1994, even U.S. court decisions tended to say that parody or satire is a favored purpose, precisely because there’s a larger move that the parody or satire is making that is extremely distinct from the underlying work. Let me bring this to Sherrie Levine. When an artist says they need to copy that picture to criticize that picture, the responding move is, “But you’re not actually saying anything about that picture; you’re saying something about Western photography.” And so there was no reason to pick on Walker Evans; you could have found someone to license and picked on them instead. That’s one of the reasons that the satire-parody distinction is so unstable.

Figure 5 Sherrie Levine, After Walker Evans no. 6, 1981. Gelatin silver print.

Adler: Lower courts, the Second Circuit, in particular, which at one point was the most liberal court on fair use—had effectively eradicated the importance of the satire-parody distinction by saying that you no longer need to comment on the underlying work, even if it’s a satire, if you’re using the work for some new transformative comment. What the Supreme Court is effectively doing here is very strongly recementing this previously crumbling parody-satire distinction and, furthermore, saying that, in the case of satire, you have to be commenting on the underlying work not just on the genre. With this case, Warhol had to be saying something about Goldsmith’s work, not about the genre of photography or about Prince or any number of other things. I think that’s a real narrowing, particularly compared to how the lower courts have been reading fair use.

Sherrie Levine, After Walker Evans no. 6, 1981. Gelatin silver print.

Adler: Lower courts, the Second Circuit, in particular, which at one point was the most liberal court on fair use—had effectively eradicated the importance of the satire-parody distinction by saying that you no longer need to comment on the underlying work, even if it’s a satire, if you’re using the work for some new transformative comment. What the Supreme Court is effectively doing here is very strongly recementing this previously crumbling parody-satire distinction and, furthermore, saying that, in the case of satire, you have to be commenting on the underlying work not just on the genre. With this case, Warhol had to be saying something about Goldsmith’s work, not about the genre of photography or about Prince or any number of other things. I think that’s a real narrowing, particularly compared to how the lower courts have been reading fair use.

Johanna Burton: I’ll jump in with a couple of thoughts about the reception of images as I’m seeing things unfold in museum settings, which may differ from that of more academic or art-historical settings. In the museum, there’s often a kind of flattened reception of materials (by flattened, I don’t mean lesser; I mean immersive and immediate), where people might not be as concerned about, or even interested in, the lineage of how the image they encounter started in one place and made its way through cycles of material culture. In the space of the here and now, images are relating to each other, architectural specificity, and audience members more immediately than to their own pasts. This dynamic is especially p. 45 heightened today, where people visiting museums are also documenting their experiences and thus creating images while or instead of looking at them.

For me, this makes the parody-satire question an especially interesting one for marking distinctions about our contemporary context insofar as parody and satire are less relevant today or, perhaps, have become so deeply baked into cultural competency as to be understood stylistically. Consider how Sherrie Levine is so often (and has been for so long) characterized as part of a critical apparatus in which commenting on the image is immediately understood as a mode of deconstructive critique. Her practice is rarely discussed as additive, though I think it can be. What might it mean to turn such long-standing assumptions on their head and to argue that Levine, for instance, piles onto and into images rather than only altering, unveiling, or subtracting from them?

By this measure, many artists (emerging and long at work) who are ostensibly using appropriation today can’t be considered “appropriation artists” in the art-historical sense. True, they are appropriators, but they have very different modalities of gathering and using images. Their images pass in and out of the frameworks they are both harvested from and newly inhabit with a different mode of consumption and distribution in mind. It’s both faster and potentially less precise, more additive and less precious, for better and for worse. “Transformation” can still happen to an image through conscious (and sometimes unconscious) recontextualization, but today I notice legal conversations around transformation revert to debates about intent and intentionality (to say nothing of ethics) on the part of the artist rather than how meaning changes as it is received by a viewer or listener who becomes coproducer in the act of receiving. We then have to remember that ’70s appropriation art is now a historical movement. So, too, our definitions of satire and parody rely on nineteenth-century ideas of political address. And I wonder if it’s worth talking about how the idea of a more additive modality of consuming images and reproducing them would affect some of these arguments.

Taking a step back, then, I think we can safely say museums have changed a lot recently. In the institution in which I work, we’re actively talking about models of presenting and learning that aren’t static and that meet audiences where they are, truly taking them—a diverse and wildly differentiated “them”—into account. That’s very unwieldy but also exciting. It’s the space where we can have different kinds of discussions around accessibility and inclusion and about how people actually bring and apply distinct modalities p. 46 of knowledge and context. Which is to say that, while critique is still incredibly useful, it must be understood within a cultural space where objects are understood as much more shape-shifting and charged things—things that in some cases are rooted in terms of shared histories but just as often represent spaces of exclusion or oppression. We can’t take the notion of a shared history for granted in any way, shape, or form. Whenever I have a hard day at work, I remind myself how lucky I am by visiting our galleries. Right now, we have Factum I and Factum II up in the museum, and some people won’t know who Rauschenberg is. And that’s okay; it’s better than okay. The job of the museum is to allow for that moment when people come in and wonder, “Why are there two?” And then they go back into the world and keep thinking about it.

So here I just want to be mindful of the material space of how things are encountered, and by whom, and how the production of the work’s meaning happens in those spaces. Though appropriation remains contentious in certain ways, I believe this indicates less any real discomfort around the act itself than it does around which creative productions of any kind get attention and, by default, which do not. As we know, people are appropriating, recycling, resharing every day, whether on their TikToks or elsewhere. Most don’t feel terribly preoccupied with legalities, because few will get sued—and the drive to appropriate is only lightly linked, if at all, to some overt desire to critique a system. Someone likes—or dislikes—an image, they hold it and mold it for a moment, and it moves on: catch and release. To come back to the museum space, if there is a political tension here, it’s because the attendant questions are real. Why is this image (but not that) considered important enough to be brought in to hang on the walls? Discussions about appropriation have always been about power and visibility. They are ultimately about who owns and who controls meaning. To that end, what shows up in museums, which are arguably outdated mechanisms in so many ways, has the ability to underscore not just the nuts and bolts of image rights but to encourage discussions around agency, propriety, and creativity. To underscore the many inequities in society, but also the deft and inspiring ways that artists model resistance, demand change. I am highly attuned to the legal outcomes of the Warhol decision, but I’m perhaps most concerned that artists not be dissuaded from their work in and around culture, so crucial to any vision for a democratic future.

Tushnet: Much of the meaning in the communities that I’m interested in, fan communities, comes from doing the work. It matters that a queer kid in Topeka is writing a story about superheroes. And so, the work itself manifests the difference in meaning that comes from that origin. We can frame it in a variety of ways, but the p. 47 value of a lot of fan engagement comes from the fact that it’s engagement. That it is work, not paid work, but productive work where you’re intervening in the world, making meaning. That was what I liked about the way that Campbell had been interpreted, although I understand that that does create interpretive difficulties. But, especially in the noncommercial world, it reflects something that is very true about making art. And, of course, for commercial artists as well, part of the meaning is in the work. The resulting object, the “work,” bears meaning because of the work you put in.

Buskirk: I really appreciated the discussion of Warhol’s use of material without concern for licensing in some of his early underground work. But that freedom of exploration, within the shelter afforded by dialogue away from mainstream attention, is less viable at this point due to the circulation of material on social media. Potential audiences are far more dispersed, and algorithms cast an even wider net. We’re in a very different place in terms of the number of takedown notices that come through automatically and the resulting lack of underground invisibility for quite young artists who would benefit from the ability to experiment and play with material from physical and virtual worlds without having to worry about requesting permission.

Burton: Today the question of copyright may offer a kind of subtle codification of a new modality of culture wars—something that has a lot more to do with how people police and track each other’s choices and make assumptions about, again, intentionality. This tracking is not reserved only for artists but has consequences for institutions as well, during our cultural moment, which is often understood via shades of transparency. People are really drilling down everywhere on how decisions are being made, which does not always get us to the “truth” but should prompt us to consider how questions of copyright law are also about power. To take up your point, Martha, even if it’s about the possibility of having invisibility, it is also about agency, agency enabled by access in every sense of the word. This is about more than copyright law. It’s about power; it’s about access; it’s about all of these things.